Imagination above all

In 1922 the young French Dada poet and future leader of the Surrealist movement André Breton denounced recent conservative trends in modern art, such as Purism, and advocated a more “thoughtful” approach.

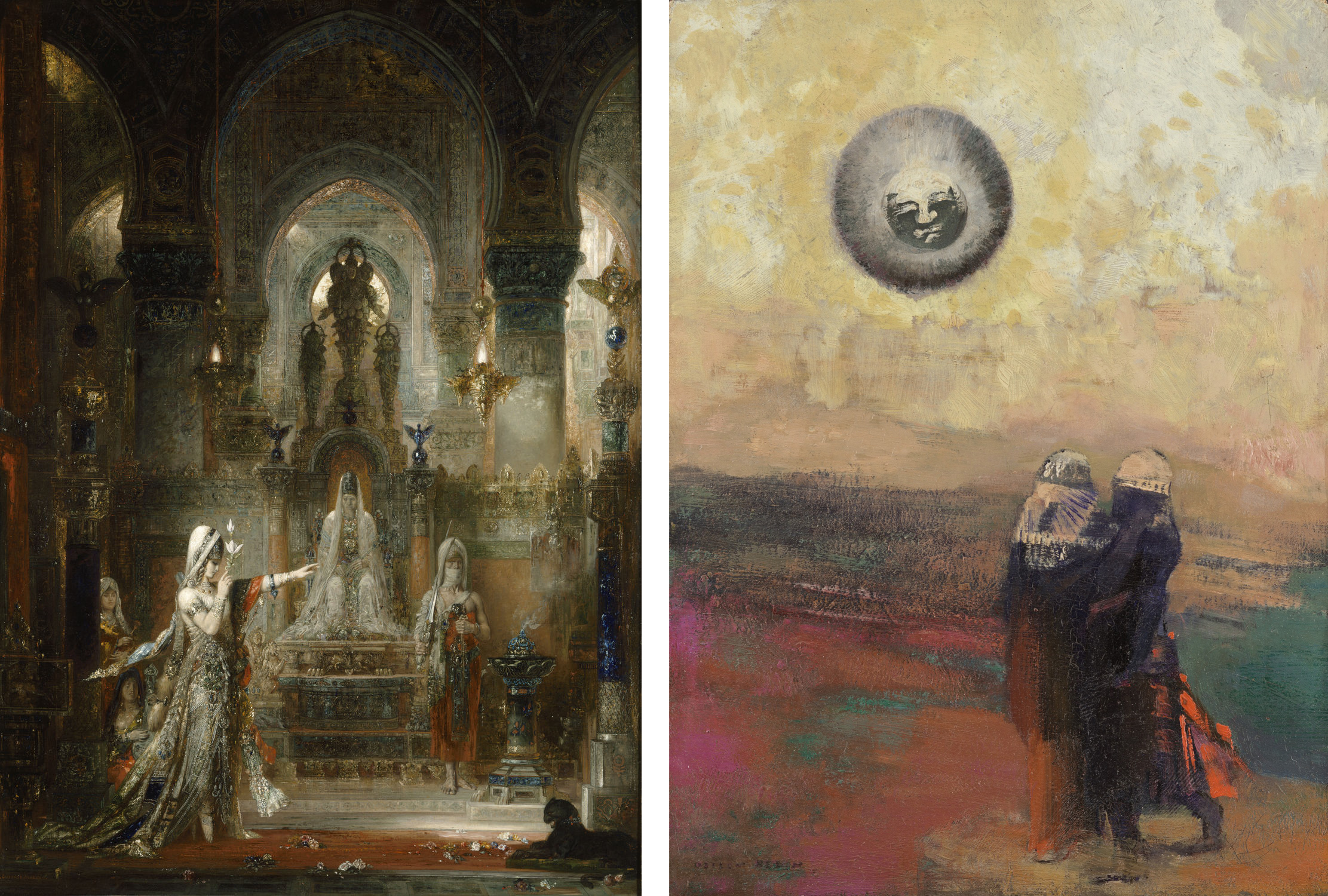

Left: Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing before Herod, 1876, oil on canvas, 58.5 x 41.1 inches (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles); Right: Odilon Redon, The Black Sun, c. 1900 oil on board, 12 3/4 x 9 3/8 inches (MoMA)

To reorient contemporary attitudes, he called for a reconsideration of the art of Pablo Picasso and 19th century artists associated with Symbolism, including Paul Gauguin, Odilon Redon, and Gustave Moreau. Symbolist artists were dedicated to the imagination and painted mysterious dream-like images drawn from mythology, the Bible, and other literary sources, as well as individual fantasy.

Breton’s early dedication to the imaginative qualities of modern art set the stage for Surrealism, a movement formally inaugurated in 1924 that placed the mental activity of the artist above all other considerations, especially the formal concerns that had become a hallmark of modern art. According to the Surrealists, the artist’s proper goal is the exploration of the arational mind and the re-creation of the world to accord with the desires of the imagination. Artists preoccupied with issues such as painting technique and formal harmonies are engaging in a trivial activity and ignoring the profound revolutionary potential of human creativity.

Dreamlike charm

Breton was a protégé of the widely admired modern poet and influential art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who had championed many important modern artists and was a close friend of Picasso. In addition to the Cubists, Apollinaire promoted Henri Rousseau and Marc Chagall, who created imaginative works in what were described as naïve styles. These painters’ works were seen as natural products of their imagination. Rousseau, who worked as a customs inspector, was a dedicated self-taught painter of imaginary exotic scenes.

Chagall was a trained artist who painted fairytale-like images that reflected his childhood memories of the Jewish community of Vitebsk, Russia (now Belarus). He was admired for his ability to incorporate the formal innovations of Fauve and Cubist painting into his fantasy scenes.

Nightmarish visions

André Breton and the future Surrealists were most impressed by another imaginative artist admired by Apollinaire, Giorgio de Chirico. Unlike Chagall, de Chirico was largely unaffected by the formal innovations of modern painting. His imaginative visions had none of the fairytale charm of the Russian-Jewish painter’s work, and compared to Chagall’s colorful kaleidoscopic dreams of flying people and animals, de Chirico’s pre-World War I paintings are ominous nightmares.

Between 1911 and 1915 de Chirico worked in Paris, creating dream-like scenes in which simplified depictions of desolate classical cityscapes are rendered in exaggerated linear perspective. Dark, threatening skies and diagonal patterns of stark shadows enhance the overall sense of menace. Occasional figures depicted in silhouette are the only living beings in de Chirico’s cityscapes, which are populated by statues and mannequins standing isolated in the twilit streets.

Also prominent in his works are enigmatic arrangements of disparate objects. In The Uncertainty of the Poet the broken torso of a Classical female nude statue confronts a bunch of bananas next to an arcade, while on the distant horizon a steam locomotive races toward the picture’s edge. Each item is carefully depicted, and the arrangement appears meaningful; however, the significance of the image remains open to interpretation. It was precisely this suggestive appeal to the imagination through the conjunction of disparate objects that attracted Breton and would form one of the principal strategies of Surrealist art.

Paris Dada and the Birth of Surrealism

In the years following World War I, Breton and other young French writers established the Dada movement in Paris. Closely involved with members from other Dada groups, including Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, and Marcel Duchamp, the Paris Dadaists developed different interests. Although they adopted the Dada strategy of attacking modern society and art through nonsensical and arbitrary actions, they gradually abandoned the Dada embrace of nonsense as a nihilistic dead end.

Under the leadership of Breton, the Paris Dadaists found a new means to revitalize the revolutionary momentum of modern literature and art in the immense potential of the unconscious mind. Influenced by his experiences working in a psychiatric hospital during the war, Breton was fascinated by recent psychological theories and discoveries. Hoping to find the ultimate source of human creativity, the Dadaists experimented with hypnosis and other methods of gaining access to subconscious mental activity. Out of these experiments Surrealism was born.

Awakening the creative resources of the mind

Adopting the term “surrealism,” earlier coined by Apollinaire, Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 and provided his own definition:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state by which one proposes to express — verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.

ENCYCLOPEDIA. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life.[1]

It is obvious from these definitions that Surrealism was conceived as much more than a new trend in literature and the arts. Its intended social agency was ultimately very broad. The goal of Surrealist writings and art was to “ruin” the logical, practical, and moral reasoning that structures human understanding of reality. Replacing such reasoning would be Surrealist thought, which through a variety of creative strategies would release the long-suppressed potential of the imagination and the unconscious mind to revolutionize reality.

Surrealist thinking was not limited to artists. Unconscious, arational thought was understood by the Surrealists as the means employed by those who discover new continents and new laws of nature; by those who invent new tools and new methods; and ultimately, by all revolutionaries whose ideas remake reality in some way. Surrealist thinking was a means accessible to everyone, and the ultimate Surrealist goal was to awaken the public to the immense creative resources of their own minds and ignite a total recreation of the world.

Notes:

- André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972), p. 26.

Additional resources:

BBC Four program on the Surrealists (contains video clips and links)