Vasily Kandinsky, Small Pleasures, 1913, oil on canvas, 110.2 x 119.4 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

At first glance, Vasily Kandinsky’s Small Pleasures appears to be an abstract painting of organic lines and blotches of bright primary and secondary colors. At the center of the composition is an inverted U surrounded by undulating, serpentine lines that frame amorphous shapes and bursts of color. What are we to make of this?

Vasily Kandinsky, With Sun, 1910, glass painting, 30.6 x 40.3 cm (Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus)

One clue is found in a painting Kandinsky made three years earlier, in which we see the same basic composition with much clearer subject matter. The inverted U is a hill, on top of which is a city with tall towers capped by onion domes (common in Kandinsky’s homeland of Russia). Waves (in blue) and fires (in yellow and orange) surge around the base, where a couple lies on the ground. Three horsemen ride up the left-hand side of the hill, while on the right three men attempt to flee in a red rowboat.

Apocalypse

This imagery is identifiable as a scene from the Apocalypse, the end of the world as described in the biblical Book of Revelation. According to St. John the Divine, before the second coming of Christ ushers in a spiritual paradise there will be a period of terrible destruction. Angels will sound their trumpets, the four horsemen of the apocalypse (war, plague, famine, and death) will be loosed, the sun will be blacked out, and the moon will become bloody. A hail of fire will burn the world, while a flood of bitter waters will drown its inhabitants (Revelation 6-9). This is what is depicted, albeit obliquely, in Small Pleasures. Between 1909 and 1913, Kandinsky painted the Apocalypse a number of times.

Vasily Kandinsky, All Saints I, 1911, glass painting, 34.5 x 40.5 cm (Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus)

In All Saints I, we can easily discern an angel on the left sounding a trumpet, flood waters rising, and fires raging, while souls emerge from their graves to be judged. Saint George, the emblem of Kandinsky’s art group Der Blaue Reiter, appears just below the angel’s arm with a number of Eastern Orthodox Christian saints, including Vladimir, Boris, and Gleb.

Out of this devastation, signs of new hope and new life emerge. A dove under the angel’s trumpet refers to the story of Noah’s flood, a prior destruction of the world by God in an attempt to purify it. Christ on the cross in the background promises resurrection after death, as do a phoenix and butterfly on the far right. (According to legend, the phoenix emerges from the ashes of its dead parent, and butterflies emerge reborn from the cocoon of the caterpillar).

In the upper left, we see a walled city with dome-capped towers next to another emblem of rebirth: the rising sun. This city is the “new Jerusalem” (Revelation 21:2), the “shining city on the hill” mentioned in Christ’s Sermon on the Mount, an echo of the promise that in the afterlife, the meek shall inherit the earth and reign with him in heaven (Matthew 5; Psalm 37).

Kandinsky’s interest in apocalyptic subject matter is related to his belief that humankind was on the verge of a cataclysmic change from the current, materialistic epoch to an “Epoch of the Great Spiritual.” Such millenarian beliefs were not uncommon at the time, particularly within the occult spiritualist movement of Theosophy.

Primitivism

Unknown artist, Anna Teaching Mary, glass painting, early 19th century (Museum für Volkskultur in Württemberg, Waldenbuch)

Another influence on Kandinsky’s work at this time was primitivism. Both All Saints I and With Sun were hinterglasmalerei, or paintings executed on the underside of glass. This technique was unusual for professional artists, but was common in folk art in Russia and southern Germany, where Kandinsky was living at the time. Kandinsky was introduced to Russian folk art when he went on an ethnological expedition to the Vologda region in northern Russia in the 1890s. He continued to look to art by amateur, Medieval, non-western and other so-called primitive artists for examples because he felt that the naturalistic style taught in professional art academies was suited only to representing the external appearances of things.

Kandinsky believed that the artist should act as a sort of shaman (originally a Russian-Siberian concept, it is worth noting) — a channel to the spiritual realm, and ultimately a guide to help lead society into the coming Epoch of the Great Spiritual. He found in folk art such as icon painting and hinterglasmalerei a non-naturalistic style better suited to his spiritual themes and ambitions.

This devotion to art associated with primitivism and spirituality also helps to explain Kandinsky’s preference for a very simplified drawing style. In hinterglasmalerei, objects are rendered in an almost childlike fashion: easily recognizable, but highly schematic, with no effort to imitate the exact appearances of what is represented.

Toward abstraction

Vasily Kandinsky, All Saints I, 1911, oil and gouache on cardboard, 50 x 64.8 cm (Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus)

There is a second, oil and gouache on board version of All Saints I that is much more abstract than the earlier version on glass. In this second painting we can barely recognize any of the subject matter, except by comparing it to the original version. Usually artists work from a quick sketch to increasingly refined detail. Why did Kandinsky do the opposite? If these paintings are intended to be about the apocalypse, why does he make their subject matter so difficult to see?

Vasily Kandinsky, Small Pleasures, 1913, oil on canvas, 110.2 x 119.4 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

The answer is twofold. First, Kandinsky hides his imagery because recognizing the objects depicted in a painting keeps the viewer’s mind anchored in our current, materialistic world of things. Stripping away the representational details of objects and reducing them to simpler, abstracted forms helps to prepare viewers for the new, spiritual epoch.

At the same time, however, Kandinsky recognizes that viewers need guidance. The purely spiritual would be incomprehensible to those who have lived all of their lives in the material world. So, in effect, he tries to have it both ways. He starts with depictions of recognizable objects and uses universal themes from mythology and religion in the comforting style of folk painting for the sake of familiarity. Then he abstracts that imagery until the psychological process of recognizing material objects in the work becomes secondary, or even subconscious. For Kandinsky, the real content of the painting should come from the work’s formal qualities: its use of color, line, and compositional rhythms.

Color vibrations

In his treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky gives special attention to color’s ability to communicate, not just sensually, but also spiritually:

Generally speaking, color is a power which directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the [viewer’s] soul.Vasily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, trans. M. T. H. Sadler (New York 1977), p. 25.

The analogy to music here is telling. Kandinsky believed that music was a more advanced form of art than painting precisely because it was more “abstract.” Music moves us emotionally and spiritually through pure form (sound vibration), without directly representing any real-world content. He believed visual artists could do the same through color vibrations, and make painting a truly spiritual art form.

“The astral body of the average man,” from Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, Man Visible and Invisible (New York, 1903), plate X

The notion that spiritual states can be conveyed through color patterns would have been familiar to many people in the early-twentieth century. Theosophists believed that certain privileged seers were able to perceive color auras that show a person’s emotional and spiritual condition. The illustration above represents the “astral body” surrounding an “ordinary lower middle-class man,” for example.

Synesthesia

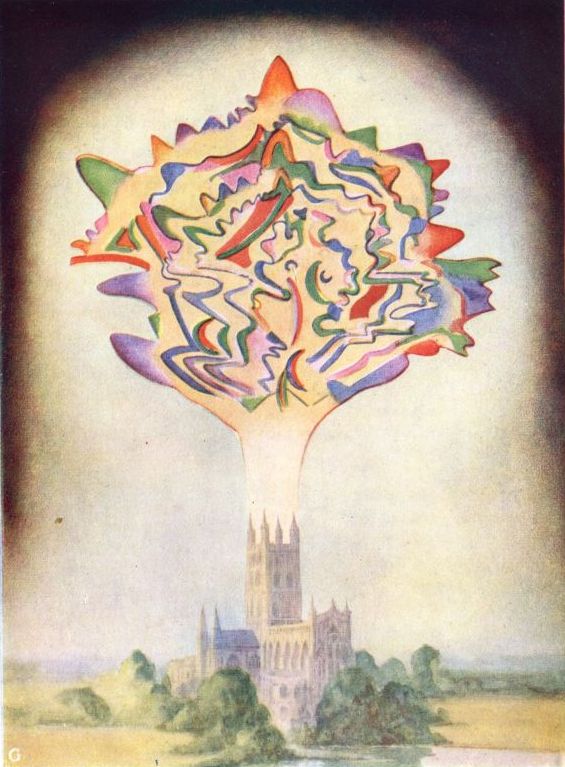

“A ringing chorus by Gounod,” from Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, Thought Forms (London, 1901), plate G

For Kandinsky, the close connections and even transferability among color, music, and spirituality were probably enhanced because he experienced a phenomenon known as synesthesia. This is a condition where sensory “wires” in the brain are in effect crossed, so that a person may experience a color as a sound, or taste as a texture. The English language recognizes this phenomenon in phrases such as “loud color” or “sharp cheese.” In another Theosophical treatise on spiritual auras, there is a striking illustration of synesthesia in the form of an abstract cloud of color emerging from a church tower, illustrating the color equivalent of what is being sung within, “a ringing chorus by [the composer Charles] Gounod.”

Vasily Kandinsky, Small Pleasures, 1913, oil on canvas, 110.2 x 119.4 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

When we look at Kandinsky’s Small Pleasures, then, we may subconsciously recognize some of the apocalyptic imagery, and that may help guide us to the spiritual content of the work. But according to Kandinsky, we should not be distracted by any material objects represented. The higher, spiritual content of the work is better communicated through pure form, through the color vibrations he carefully orchestrated to resonate in our souls.

Additional resources:

Read Man Visible and Invisible at the Internet Archive