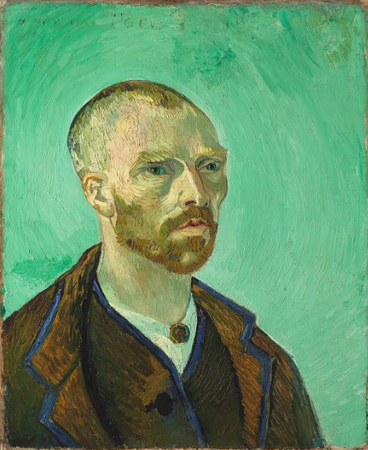

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, 1888, oil on canvas, 24 x 19-11/16″ (Fogg, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re looking at a painting in the Fogg’s collection. It’s a very famous self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh — Vincent van “Gakh.” It’s one of the toughest self-portraits I think I’ve ever seen.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:16] Tough in terms of the color, tough in terms of all that Van Gogh was achieving at this moment in the late 1880s.

Dr. Zucker: [0:24] This is a painting that feels incredibly modern to me, a willingness to take risks…

Dr. Harris: [0:29] It’s amazing in that way.

Dr. Zucker: [0:30] …that are breathtaking, really, yeah.

Dr. Harris: [0:31] This is a color that no artist ever used before, and an entire background painted like that? What nerve he had to take such radical steps.

Dr. Zucker: [0:41] My eye immediately goes to the structure of the painting, the way in which he’s created the architecture of the face, his use of line. I look at the way in which the brushstrokes wrap around and sort of cascade around the eye and down the nose. It’s almost like a river of paint as it flows across that face and begins to define it. But then it’s not just brushwork at all. It’s the ways in which structure is actually built by color.

Dr. Harris: [1:07] By color, which I think was something that Cézanne was also thinking about, creating volume with color instead of in the usual way with chiaroscuro. But the pinks and the purples that are in his temple and the way those modulate over to greens is like nothing I’ve ever seen.

Dr. Zucker: [1:26] He’s treating the structure of his face, of his head, of his skull very much as if it was a kind of plastic medium. He writes about this portrait that he has created eyes almost as if he was Japanese — a reference to his love of East Asian painting. This was a painting that was destined as a gift to Gauguin, as part of an exchange.

Dr. Harris: [1:45] Right, with this utopian idea of a brotherhood of artists that was so important to him.

Dr. Zucker: [1:51] Of course, Gauguin also would have been very interested in East Asian art. This way that he’s rendered the hair on his head, plastered down, it’s in really strong contrast, visually, to the way in which the coat feels heavy and rough and oversized. Then there’s the very tight quality…

Dr. Harris: [2:09] To his skin.

Dr. Zucker: [2:09] …to his skin, yeah.

Dr. Harris: [2:10] I was noticing that, too. What it was reminding me of was a skull, the sense of the bones underneath his flesh and almost a kind of memento mori. Look at the browns and the blues, rust colors in his jacket, and…

Dr. Zucker: [2:27] This green. This sea of acid light that surrounds him.

Dr. Harris: [2:33] He is just an amazing colorist.

[2:36] [music]

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, 1888, oil on canvas, 61.5 x 50.3 cm (Fogg, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA)

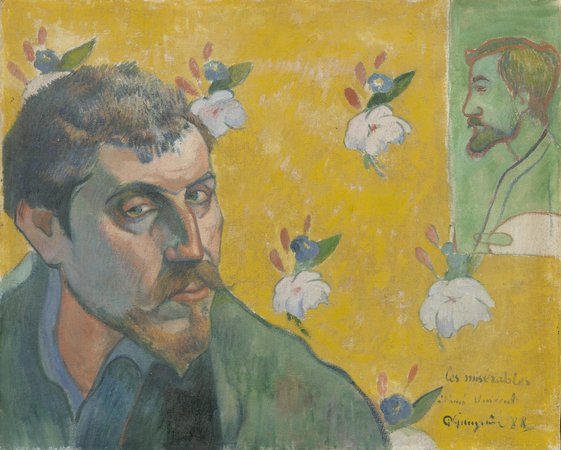

This self portrait was painted for Paul Gauguin as part of swap between the artists. Van Gogh chose to represent himself with monastic severity. The other painting is Paul Gauguin’s Self-Portrait Dedicated to Vincent van Gogh (Les Misérables). Gauguin’s title is a reference to the heroic fugitive, Jean Valjean, in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables. Gauguin’s painting also contains a portrait of Emile Bernard that was painted not by Gauguin but by Bernard within Gauguin’s painting.

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Vincent van Gogh (Les Misérables), 1888, oil on canvas, 44.5 x 50.3 cm (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam)

The following is a letter by Van Gogh to his brother Theo about the painting exchange with Gauguin dated October 7, 1888:

My dear Theo,

Many thanks for your letter. How glad I am for Gauguin; I shall not try to find words to tell you – let’s be of good heart.

I have just received the portrait of Gauguin by himself and the portrait of Bernard by Bernard and in the background of the portrait of Gauguin there is Bernard’s on the wall, and vice versa.

The Gauguin is of course remarkable, but I very much like Bernard’s picture. It is just the inner vision of a painter, a few abrupt tones, a few dark lines, but it has the distinction of a real, real Manet.

The Gauguin is more studied, carried further. That, along with what he says in his letter, gave me absolutely the impression of its representing a prisoner. Not a shadow of gaiety. Absolutely nothing of the flesh, but one can confidently put that down to his determination to make a melancholy effect, the flesh in the shadows has gone a dismal blue.

So now at last I have a chance to compare my painting with what the comrades are doing. My portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin in exchange, holds its own, I am sure of that. I have written to Gauguin in reply to his letter that if I might be allowed to stress my own personality in a portrait, I had done so in trying to convey in my portrait not only myself but an impressionist in general, had conceived it as the portrait of a bonze, a simple worshiper of the eternal Buddha.

And when I put Gauguin’s conception and my own side by side, mine is as grave, but less despairing. What Gauguin’s portrait says to me before all things is that he must not go on like this, he must become again the richer Gauguin of the “Negresses.”

I am very glad to have these two portraits, for they finally represent the comrades at this stage; they will not remain like that, they will come back to a more serene life.

And I see clearly that the duty laid upon me is to do everything I can to lessen our poverty.

No good comes the way in this painter’s job. I feel that he is more Millet than I, but I am more Diaz then he, and like Diaz I am going to try to please the public, so that a few pennies may come into our community. I have spent more than they, but I do not care a bit now that I see their painting—they have worked in too much poverty to succeed.

Mind you, I have better and more saleable stuff than what I have sent you, and I feel that I can go on doing it. I have confidence in it at last. I know that it will do some people’s hearts good to find poetic subjects again, “The Starry Sky,” “The Vines in Leaf,” “The Furrows,” the “Poet’s Garden.”

So then I believe that it is your duty and mine to demand comparative wealth just because we have very great artists to keep alive. But at the moment you are as fortunate, or at least fortunate in the same way, as Sensier if you have Gauguin and I hope he will be with us heart and soul. There is no hurry, but in any case I think that he will like the house so much as a studio that he will agree to being its head. Give us half a year and see what that will mean.

Bernard has again sent me a collection of ten drawings with a daring poem – the whole is called At the Brothel.

You will soon see these things, but I shall send you the portraits when I have had them to look at for some time.

I hope you will write soon, I am very hard up because of the stretchers and frames that I ordered.

What you told me of Freret gave me pleasure, but I venture to think that I shall do things which will please him better, and you too.

Yesterday I painted a sunset.

Gauguin looks ill and tormented in his portrait!! You wait, that will not last, and it will be very interesting to compare this portrait with the one he will do of himself in six months’ time.

Someday you will also see my self-portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin, because he will keep it, I hope.

It is all ashen gray against pale veronese (no yellow). The clothes are this brown coat with a blue border, but I have exaggerated the brown into purple, and the width of the blue borders.

The head is modeled in light colours painted in a thick impasto against the light background with hardly any shadows. Only I have made the eyes slightly slanting like the Japanese.

Write me soon and the best of luck. How happy old Gauguin will be.

A good handshake, and thank Freret for the pleasure he has given me. Good-by for now.

Ever yours,

Vincent.[1]