Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1855, oil on panel, 82.5 x 75 cm (Birmingham Museums Trust)

A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris.

Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1852-55, oil on panel, 82.5 x 75 cm (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, UK)

Ford Madox Brown’s great modern life study The Last of England (1852-55) captures a familiar scene in England during the 1850s. A man and woman aboard a crowded ship gaze out at the viewer. A brisk wind blows the woman’s bonnet ties and turns the sea into a mass of white caps, suggesting the potential for a rough passage. The deck behind them is packed with people also making the journey, while green cabbages hanging on the rope railings hint at the long voyage ahead. The predominately somber color scheme, the chilly look of the sea and the sky, and the mournful expressions of the main figures tell the story.

Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1852-55, oil on panel, 82.5 x 75 cm (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, UK)

The painting is dominated by the two figures, based on the artist and his wife, Emma. Their close proximity and clasped hands identify them as a couple, yet they both stare straight ahead, each locked in their own silent reflections. Barely noticed at first glance is the small hand emerging out of the woman’s cloak, the unseen child that is potentially a nod to the future. The umbrella propped up to shield them from the spray of the sea also blocks their view of the iconic white cliffs of Dover receding in the distance, representing what is left behind. The unusual circular format of the painting acts almost like a telescope, adding a voyeuristic quality to the scene, as if the viewer is spying on this moment of personal grief and introspection. In a catalogue of his paintings written in 1865, Brown described The Last of England as “the parting scene in its fullest tragic development.” He also alludes to the superior class status of the couple compared to most of those in the background as “a couple from the middle class, high enough, through education and refinement, to appreciate all they are now giving up.”

Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, detail of child’s hand inside cloak, 1852-55, oil on panel, 82.5 x 75 cm (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, UK)

Inspiration for the painting came from the departure of the sculptor Thomas Woolner, an original member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who joined the exodus to dig for gold in Australia in 1852. This came during a period of massive emigration from Britain—between circa 1815 and 1914 approximately ten million people sailed away, primarily to the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, hoping to improve their personal prospects. Unlike Woolner, who returned (without gold) to England in 1854, many of these people never saw their homeland again. Nor were they expected to return, which explains the couple’s mournful expressions. Other painters of the day addressed the subject of emigration, most notably Richard Redgrave in his The Emigrant’s Last Sight of Home (1858). However, Redgrave’s depiction of a family leaving a small village to begin their long journey is far more optimistic. In Redgrave’s work, the sunny sky, vivid green landscape, and the father’s theatrical wave of his hat as a final gesture of farewell create a feeling of hope largely missing from Brown’s painting.

Richard Redgrave, The Emigrant’s Last Sight of Home, 1858, oil on canvas, 67.9 x 98.4 cm (Tate, London)

Brown worked on this image over a period of years. Painted for the most part in his backyard, the artist worked on cold days using his family and local people as models. For example, when the painting was nearing completion, he recorded in his diary “it was the weather for my picture & made my hand look blue with the cold as I require in the work, so I painted all day out in the garden.” The minute detail of the purplish flesh on the exposed hands of the man in the foreground attests to Brown’s attention to detail. The glowering expression on the man’s face may also relate to Brown’s own emotions, as at the time he was struggling to achieve commercial success and himself entertained the idea of emigration.

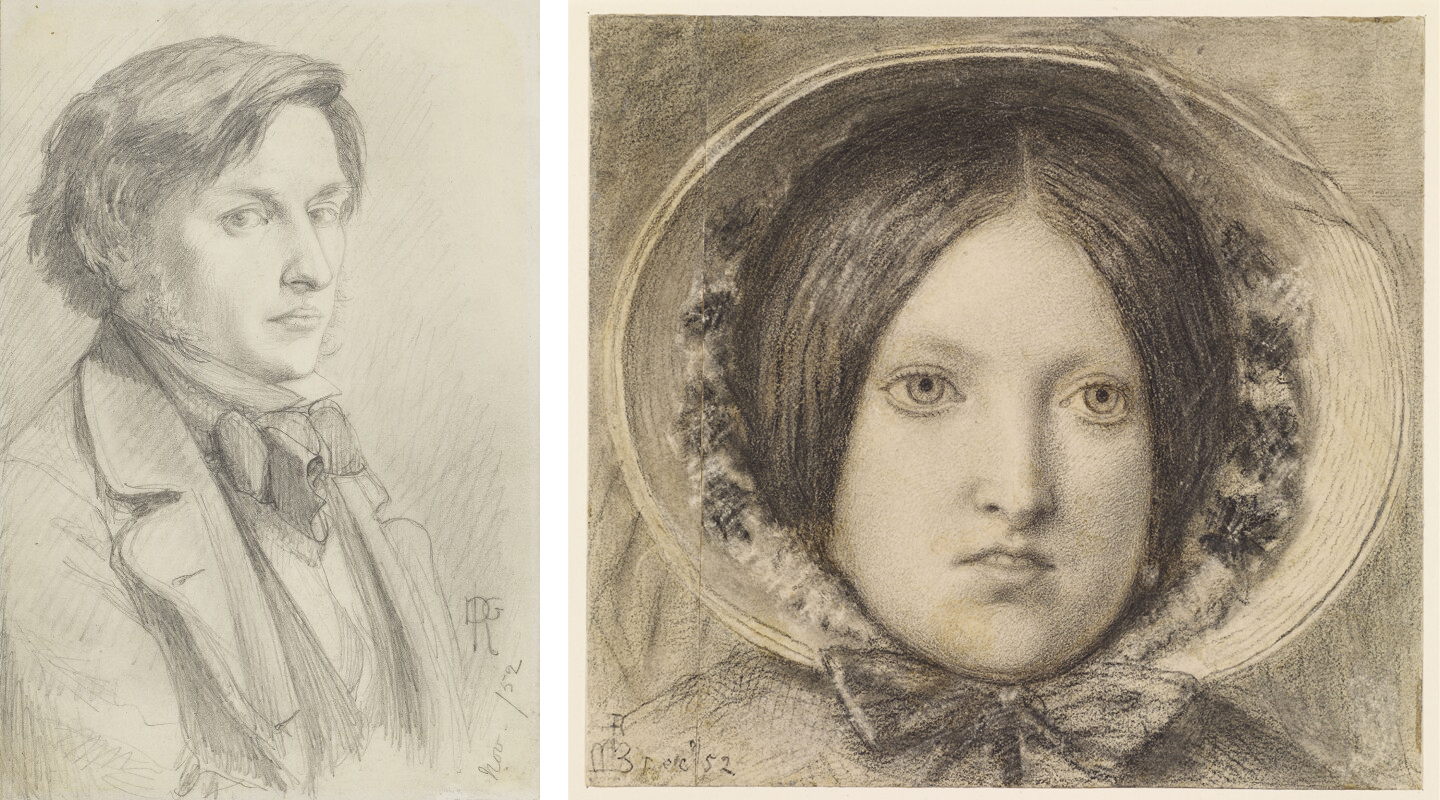

Left: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Madox Brown, 1852, pencil on wove paper, 17.1 x 11.4 cm (National Portrait Gallery, London); right Ford Madox Brown, Emma Hill, 1852, chalk on paper, 17.7 x 16.1 cm (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, UK)

The Last of England is a poignant reminder of the journey made by millions of people during the 19th century. At a time when many people are interested in genealogy and learning where they came from, it is a visual reminder of the hope and despair that these emigrants must have felt as they left their homes and families behind in search of a better life.

Additional resources:

A watercolor version of The Last of England at the Tate

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”FMB-lastengland,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in Birmingham, looking at one of the most famous paintings by Ford Madox Brown. This is “The Last of England.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] Brown was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. That group sought to create a kind of painting that, as the art critic Ruskin said, “involved truth to nature.” In this painting of an emigrant family on a ship leaving England, we can really see Ruskin’s idea of truth to nature.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] You can see it in the careful handling of the light that you would find on a bright but overcast day, and the way that that light infuses different kinds of surfaces.

Dr. Harris: [0:46] Making this truthful to what this looked like was important to the artist. He painted portions of it outdoors. In fact, there’s a passage from his diary where he’s happy that it’s very cold because that allows him to paint the way that one’s skin turns a bit blue in the cold.

Dr. Zucker: [1:04] You can see that in the right hand of the man in the foreground.

Dr. Harris: [1:07] There was a wave of emigration in the 1840s and 1850s, where many people sought a better life in the United States or in Australia, and Brown himself thought about emigrating to India.

[1:22] It’s important to remember that the decade before this was called the Hungry Forties, a decade of tremendous conflict between the classes, widespread unemployment, of strikes, of people going hungry. And so this hardship would lead one to think about leaving one’s home country to have a better life for one’s family.

Dr. Zucker: [1:47] The seriousness of the situation of the primary figures could not be more directly expressed.

Dr. Harris: [1:53] Although we’re meant to read them as a typical middle-class couple forced to take this voyage, they are modeled after the artist himself and his wife, Emma.

Dr. Zucker: [2:03] You can just make out the hand of the child that she holds under her wrap. In fact, just the turn of the child’s head and the child’s sock peeking out. In a sense, we also have references to the tradition of religious painting.

[2:17] This is, in some ways, a representation of the Holy Family, and the artist has created almost a halo-like series of concentric circles that surround the woman’s head, her braids, her ribbon, and her bonnet.

Dr. Harris: [2:32] We’re also looking at Brown’s ideas and Victorian ideas of the way that men and women differently experience the world. She has got her family, therefore all she needs. I think that that’s, for me, most poignantly shown in the hands — the child’s hand that grips its mother.

[2:50] Also, her gloved hand, which holds her husband’s hand so tightly that his fingers get squished a little bit together. You feel her reliance on him. He is the strength of the family. He is what keeps the family together.

Dr. Zucker: [3:06] This painting is a product of 19th-century ideas of patriarchy, of family, and of gendered roles.

Dr. Harris: [3:13] This is also a commentary on the problems faced by artists in the mid-19th century.

Dr. Zucker: [3:20] This is also a painting that’s meant to invite close looking, because the artist has lavished on it not only tremendous attention to the light but also to the textures, to the complex environment of a small ship where people are forced together. In this case, where people of different social classes are brought together.

Dr. Harris: [3:40] Brown has made it very clear that the couple are slightly higher in class than the other figures behind them. We see what he described as a grocer’s family, a little girl eating an apple, a man smoking a pipe, and then two men who look slightly drunk.

[3:57] One who’s shaking his fist as he looks at the white cliffs of the shoreline of England, a man who Brown described as shaking his fist at his country and blaming his country for not providing for him. Behind that, a figure who’s unloading groceries onto the boat. So this kind of chaotic group of figures who are coming together.

Dr. Zucker: [4:20] The level of detail is tremendously precise. The enormous amount of time that the artist took to render this oil on panel is evident in the fabric of the woman’s cloak, of the man’s coat. You can make out the individual droplets of water on the rope or on the cabbages that the passengers will eat during their journey.

[4:39] Or the way in which the spray from the waves are gathering in droplets on the outside of the umbrella. Then there’s the way in which the woman’s ribbons are being whipped around by the wind and a series of beautiful compositional echoes.

[4:53] You see an arc made by the string that ties the man’s hat to his button so that the wind won’t make off with it. That arc is echoed by his shoulder, echoed again by the pipe, echoed again by the arm that holds the life raft in the background.

[5:08] There are a series of formal relationships that the artist has carefully constructed in order to make sure that the image remains unified, for all the chaos that he’s displaying.

Dr. Harris: [5:20] My favorite passage is the tassels on her gray woolen shawl, which are painted with such care. This reminds us of this Pre-Raphaelite principle of truth to nature, of painting what one sees. Moving away from the academic style, which generalized forms, which used loose, open brushwork, which relied on academic formulas that had been in place since the Renaissance.

Dr. Zucker: [5:51] And so we’re left with this image of this family that is facing a cold, dark, windy, storm-tossed sea. Trying to protect themselves from this weather, just as they’re trying to protect themselves from the economic storm that they found themselves in in England.

[6:07] [music]