In Part 1 of this introduction to Neo-Impressionism we examine the style of the movement, concentrating on the artists’ attempt to systematize a method for painting according to scientific laws of perception, color, composition, and expression. Here, we will turn to the kind of subject matter typically chosen by the Neo-Impressionists and discuss its relation to late-nineteenth century social and political history.

Scenes of leisure

For the most part, the Neo-Impressionists continued to depict the kinds of subjects preferred by the Impressionists: landscapes and leisure scenes. In addition to his famous painting of people lounging in the park on the island of La Grande Jatte, many of Georges Seurat’s paintings portrayed entertainments such as the circuses and music halls that contributed to Paris’s reputation for mass spectacles in the late nineteenth century.

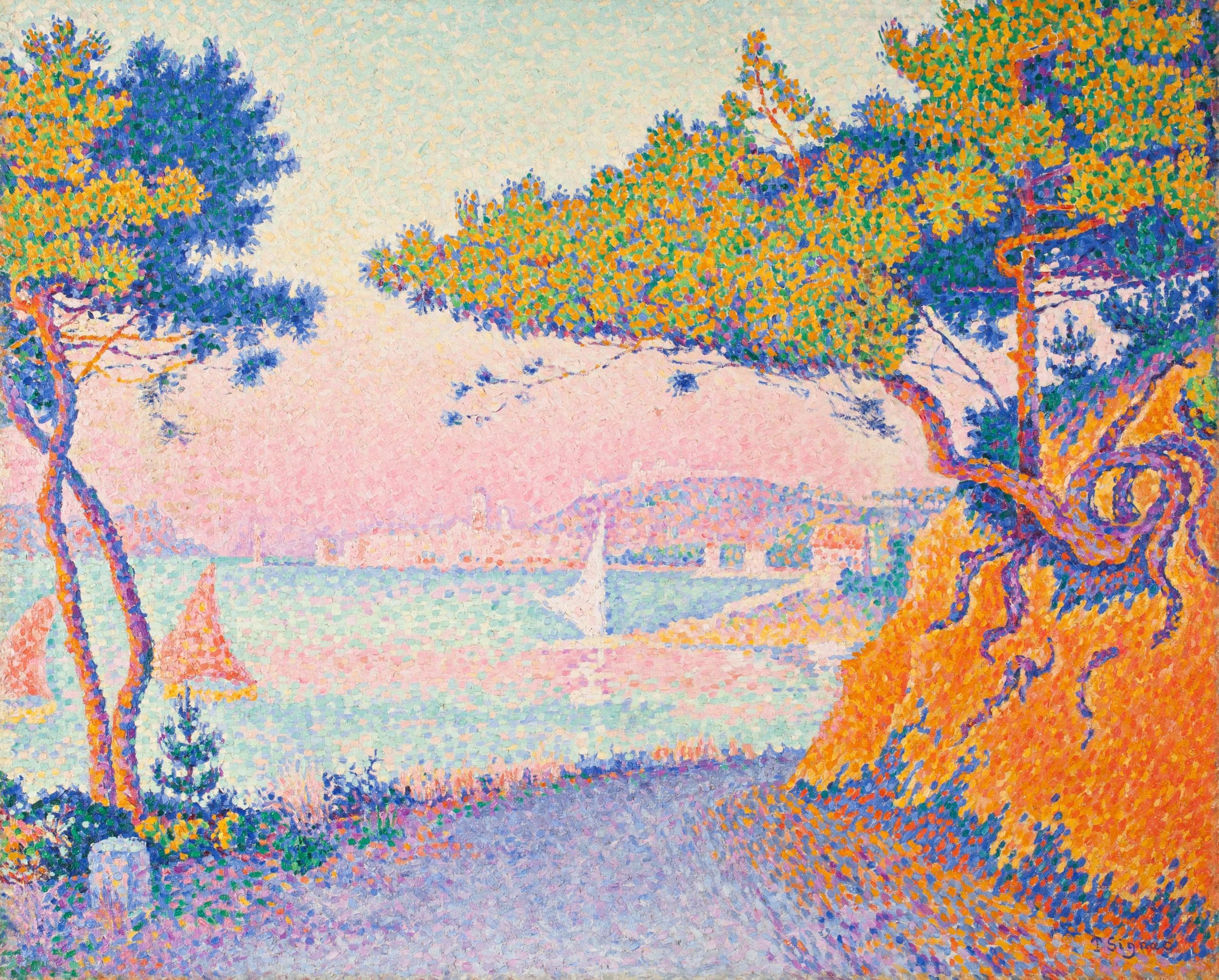

Paul Signac’s landscape paintings similarly reveal a concentration on leisure scenes. A sailor himself, Signac painted dozens of harbor scenes dominated by the sails and masts of small pleasure craft. The Mediterranean coast of France, where Signac spent his summers, had a reputation both for the quality of its light — a key interest of the Neo-Impressionists generally — and for a laid-back, sun-filled lifestyle. In Signac’s canvases, the bright colors favored by the Neo-Impressionists perfectly complement this reputation.

Social inequality

Although these subjects suggest carefree pleasure, there are undertones of social criticism in some Neo-Impressionist paintings. Seurat’s Circus shows the strict class distinctions in Paris both by location, with the wealthier patrons seated in the lower tiers, and by dress and posture, which gets markedly more casual the further the spectators are from ringside.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884-86, oil on canvas, 207.5 x 308.1 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

One contemporary critic also remarked that the rigidity of the poses in Seurat’s La Grande Jatte reminded him of “the stiffness of Parisian leisure, prim and exhausted, where even recreation is a matter of striking poses.” [1] As we examine the characters in La Grande Jatte in detail, there are some surprising inclusions and juxtapositions. In the left foreground, a working-class man in shirtsleeves overlaps a much more formally-dressed middle-class gentleman in a top hat holding a cane. A trumpet player in the middle-ground plays directly into the ears of two soldiers standing at attention in the background. A woman with an ostentatiously eccentric pet monkey on the right and another fishing on the left have been interpreted as prostitutes, one of whom is casting out lures for clients. Between them, a toy lap-dog with a pink ribbon leaps toward a rangy hound whose coat is as black as that of the bourgeois gentleman with the cane.

Despite these provocative juxtapositions and overlaps, very few of the figures actually seem to be interacting with each other; each is lost in their own world. Unlike the mood of convivial good-fellowship between the classes and sexes in Auguste Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette, Seurat’s Grande Jatte sets up a dynamic of alienation and tension.

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884, oil on canvas, 201 x 300 cm (National Gallery of Art, London) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

La Grande Jatte forms an implicit pair with an earlier painting of the same size by Seurat, Bathers at Asnières. Asnières was an industrial suburb of Paris, just across the river Seine from La Grande Jatte. Unlike that island’s largely middle-class patrons in their top hats and bustle skirts, here we see more working-class and lower-middle-class figures in shirtsleeves and straw hats or bowlers. In the background the smokestacks of the factories at Clichy serve as a reminder of labor, even during the men’s leisure time.

As in the painting of La Grande Jatte, all of the figures are isolated in their own world, but a sense of implicit tension is raised by their insistent gaze across the river at their wealthier compatriots. A middle-class couple being rowed by a hired oarsman in a boat with a prominent French flag further adds to the class tensions raised by the work.

Political revolutionaries?

Perhaps it was this odd sense of unresolved class tensions that caused Signac to suggest that even Seurat’s paintings of “the pleasures of decadence” are about exposing “the degradation of our era” and bearing witness to “the great social struggle that is now taking place between workers and capital.” [2] Seurat’s own politics were unclear, but Signac was a social anarchist, as were several other Neo-Impressionists, including Camille Pissarro and his son Lucien, as well as Maximilian Luce, Theodore van Rysselberghe, Henri Cross, and the critic Felix Fénéon. Social anarchists reject a strong centralized government in which the state owns the means of production and guides the economy; they believe that social ownership and cooperation will emerge naturally in a stateless society.

Paul Signac, In the Time of Harmony, 1893-95, oil on canvas, 297 x 396 cm (Hôtel de Ville, Montreuil, France)

Signac’s In the Time of Harmony was originally titled In the Time of Anarchy, but political controversy forced a change. Between 1892 and 1894 there were eleven bombings in France by anarchists, and a very public trial of suspected anarchists that included Fénéon and Luce.

Signac’s painting was intended to show that, despite its current revolutionary tactics, the aim of anarchism was a peaceful utopia. In the foreground, workers lay down their tools for a picnic of figs and champagne while others play at boules. A couple in the center contemplates a posy, while behind them a man sows and women hang laundry. Although the mood is timeless — with different clothing, this painting could be a Classical pastoral scene — in the distance modern mechanical farm equipment reinforces the painting’s subtitle, “The Golden Age is Not in the Past, it is in the Future.”

Relatively few Neo-Impressionist paintings are so overtly allegorical and political. Signac argued that it was the Neo-Impressionists’ technique, not any directly socialist or anarchist subject matter, that was most in tune with the political revolutionaries. The Neo-Impressionists’ rigorous appeal to hard science, rather than dead conventions, along with their uncompromising will to “paint what they see, as they feel it,” will help “give a hard blow of the pick-axe to the old social structure” and promote a corresponding social revolution. [3]

Notes:

- Henri Fèvre, “L’Exposition des Impressionnistes,” in Étude sur le Salon de 1886 et sur l’exposition des impressionnistes (Paris, 1886), p. 43 (our translation).

- Paul Signac, “Impressionists and Revolutionaries,” La Révolte, June 13-19, 1891, as translated in Nochlin, ed., p. 124.

- ibid., p. 124.