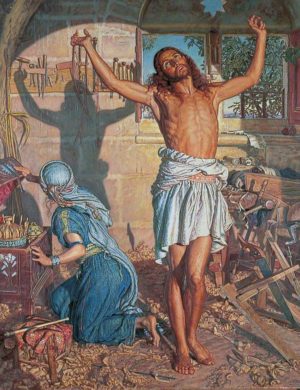

William Holman Hunt, The Shadow of Death, 1870–73, retouched 1886, oil on canvas, 214.2 x 168.2 cm (Manchester Art Gallery)

Of the original members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, William Holman Hunt was the artist who stayed closest to the ideal of truth to nature (painting from direct observation of the visible world) promoted by the group. Hunt, who was raised by devout Christian parents, was also the painter most interested in pursuing religious subjects. His 1873 picture entitled The Shadow of Death is a powerful combination of these two concepts.

The Shadow of Death is an extremely large painting depicting Jesus as a young man in the carpenter’s shop. As Jesus stretches out his arms, his shadow, combined with a wooden plank covered with hanging tools attached to the wall behind, creates a graphic foretelling of the scene of the crucifixion.

At Christ’s feet is his mother, the Virgin Mary, who faces away from the viewer, opening a large box containing the gifts from the Magi.Hunt’s emphasis on the muscled torso and arms of Christ indicate the physical nature of his work, and the dusty feet of both figures reflect the reality of dirt floors. The emphasis on the actual labor of being a carpenter also reflects the Victorian belief in the virtue of hard work often praised by writers of the time.

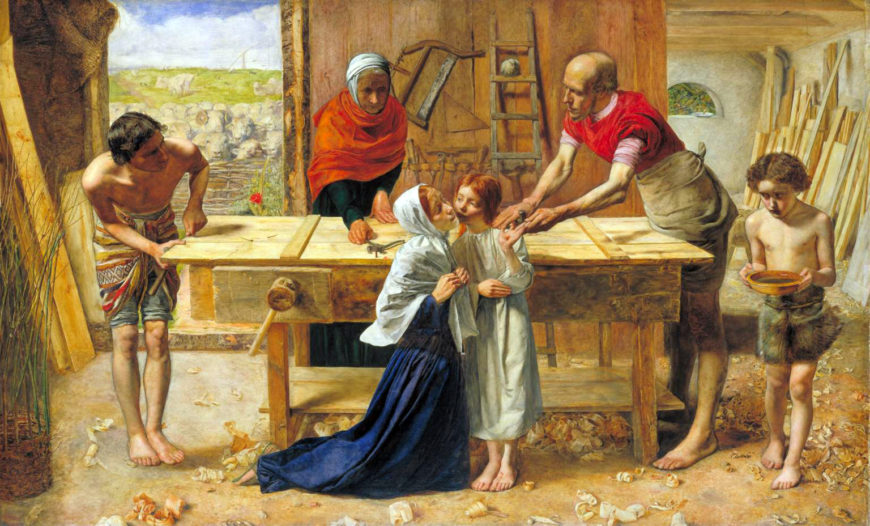

Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents (‘The Carpenter’s Shop’), 1849–50, oil on canvas, 86.4 x 139.7 cm (Tate)

Other details exhibit Hunt’s continued adherence to Pre-Raphaelitism. The curly wood shavings that cover the floor are even more numerous and beautifully painted than those in the Millais’s earlier depiction of the carpenter’s shop, Christ in the House of his Parents. The precise tools of the carpenter’s trade hang in an organized way against a roughly textured stone wall. Close examination of Mary’s dress, which reads as the traditional blue from a distance, reveals weaving containing a mix of blues and greens, while bracelets in blue and silver decorate her also well-muscled arm. Kneeling before the elaborately carved box, Mary is distracted by looking at the shadow on the wall, away from the carefully stored gifts given to her son so long ago. Each detail tells a piece of the story and hints at its inevitable conclusion.

Hunt was one of the few Victorian artists who believed that to truly explore religious subjects, it was necessary to actually go to the Holy Land to paint. Hunt first traveled to the Holy Land in 1854 and his works from this trip are some of the more unusual of the period. For example, his painting The Scapegoat exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856, is one of the most striking and unconventional religious paintings of the time.

Smaller version: William Holman Hunt, The Shadow of Death, 1870-73, retouched 1886, oil on canvas, 94 x 73.6 cm (Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds Museums and Galleries)

The Shadow of Death dates from Hunt’s second major trip to the Holy Land from 1869–72. The painting was begun on a smaller canvas (now in the Leeds Art Gallery) in a carpenter’s shop in Bethlehem to get the right atmosphere, an important part of the artist’s determination to make his paintings as truthful to nature as possible. The artist then began a larger version of the subject and even had a hut constructed on the roof of his rented house in Jerusalem so he could better control the angle of the light in order to achieve the desired effect.

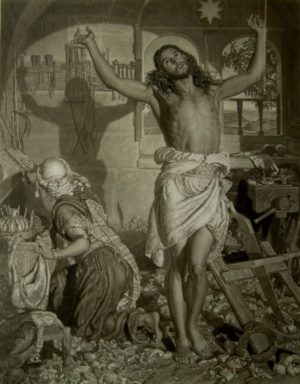

After William Holman Hunt,The Shadow of Death, mixed method engraving by Frederick Stacpoole, published by Thomas Agnew and Sons, 1878, 28 3/4 x 22 3/4 inches (Maas Gallery)

Working on both versions of the picture simultaneously, he at one point actually considered destroying the large version due to his frustrations over translating the subject into so large a picture. Hunt’s diary records that he thought it extremely difficult to capture “truth to nature on such a large scale.” However, when Hunt returned to England in 1872 both versions returned with him. The larger painting was not completed until 1873 when it was purchased by the London dealer Agnew’s and finally exhibited in November of that year. Although there was some critical disapproval of his grittier representation of Christ, the painting proved to be popular and sold well as an engraving.

The Shadow of Death shows Hunt at the height of his powers, able to create an exquisitely detailed and moving work of art. His Pre-Raphaelite insistence on “truth to nature” stayed with him throughout his career, and his explorations of the Holy Land speak to his tenacity in making sure everything was as realistic as possible. The Shadow of Death is an inspired representation of a youthful Christ who cannot escape his destiny.

Additional resources

This painting at the Manchester Art Gallery