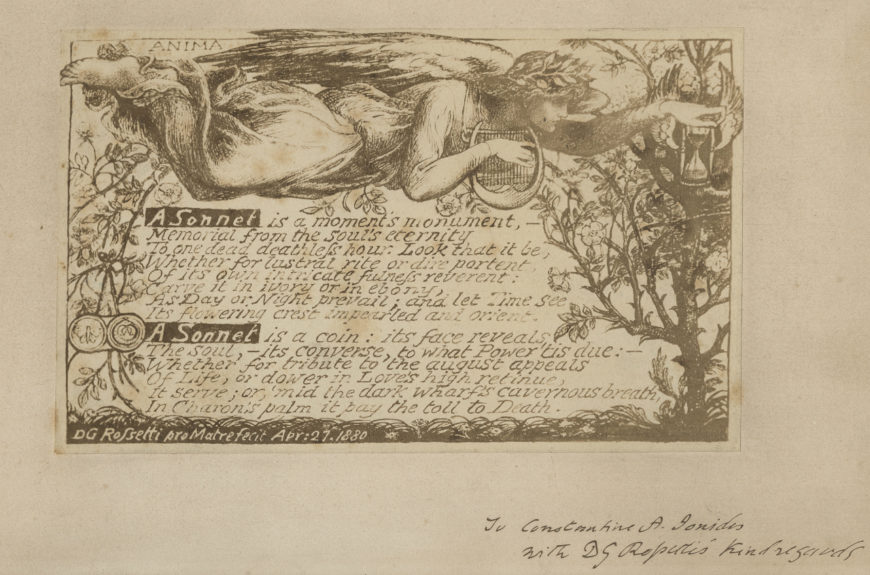

If monuments are traditionally supposed to endure the test of time, how do you create “a moment’s monument”? How do you make a sculptural monument —in stone, bronze, or marble—that captures the transitory, the fleeting aspects of modern life? The Impressionists accomplished this in their paintings during the nineteenth century, but could three-dimensional sculpture do the same? This is the question that preoccupied the Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso throughout his career. He found his answer in his final subject, Ecce puer (Behold the Child). It was a response that involved a complete rethinking of the ways in which light can affect a sculptural surface. A haunting image of emergence and disappearance, Ecce puer brought together Rosso’s explorations of the optical and emotional effects of light on three-dimensional art and helped open the door to the birth of modern sculpture in the twentieth century.

Medardo Rosso, Ecce puer, 1906, wax, 43 x 66 cm (Galleria Ricci-Oddi in Piacenza)

Creation myths

The exact details of how Ecce puer came about are not clear, but we know that some time between February and October 1906, during a visit to London, Rosso was commissioned by the wealthy industrialist and art collector Emile Mond and his wife, Angela, to make a portrait of their son Alfred William, who was four or five years old. Rosso brought the clay to the family’s lavish home, but had a hard time finding the inspiration to make the portrait.

A sudden play of light washing over the child’s face seems to have been the impetus that led Rosso to be able to sculpt. According to family legend, he saw little Alfred behind a parted curtain, while others say that he glimpsed the child in the first ray of morning light. One critic wrote that the child suddenly showed up in the artist’s room, when “a wave of light, that was not the same one of the other days, invests [the child], and Rosso sees him as he has never seen him before: he sees him in his poetic and expressive reality.” [1] These accounts are likely more mythologized than factual, however, since normally the child would have been required to sit before the artist for a long period of time for a commissioned portrait. These stories contribute to the legend of Rosso “glimpsing” things that quickly appear and disappear. They speak to his idea of modern sculpture as something created from light suddenly striking a surface. Whatever the true details of how this work came to be, the enigmatic yet moving portrait, which Rosso later retitled Ecce puer (Latin for “Behold the Child”), appears barely glimpsed or scarcely recorded. It feels as if the child’s face is emerging and disappearing at the same moment.

Reaction

Emile and Angela Mond considered the portrait to be a failure and rejected Rosso’s completed work, claiming that it did not resemble their child. Perhaps it unnerved them to see their son depicted in this way. Rosso was devastated, but critics applauded the sculpture as his masterpiece. One critic considered Ecce puer to be an “an uncanny transmission of life,” [2] while others felt it recalled the mysterious Holy Shroud of Turin that was thought to have covered Christ’s face, leaving his imprints on the sacred cloth. Still other critics saw it as an artistic abstraction or a desire “to unwill the corporeality of sculpture.”[3] One critic, following a sonnet by the British poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, poetically described Ecce puer as “a moment’s monument.” [4]

Ray of sunlight strikes the young Lucius Caesar(?), north procession, Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), 13 B.C.E.

The role of light in sculpture

Modern painters in the nineteenth century, most notably the French Impressionists and the Italian Macchiaioli, had successfully used the technique of breaking up surfaces to create the illusion of light in their art. Their works prefigured the art of French Impressionists. Unlike the Impressionists, however, the Macchiaioli’s subjects were not celebrations of modernity or modern life. Instead the Macchiaioli depicted figures often immersed in timeless visions of the Tuscan landscape.’]Macchiaioli[/simple_tooltip], had successfully used the technique of breaking up surfaces to create the illusion of light in their art. But sculpture was different: sculptures are solid three-dimensional objects that contend with the effect of actual external illumination. In a seminal essay of 1846, “Why Sculpture Is Boring,” the French poet Charles Baudelaire pointed out that sculptors could not control the lighting conditions in which their work was seen: “and it often happens, and this is humiliating for the artist, that a chance ray of light or the play of lamplight throws into relief a beautiful effect not intended by the artist.” [5] For Baudelaire, sculpture could not compete with painting because “a picture is nothing but what it intends to be. There is no way of looking at it except in its own light.” To Baudelaire’s mind, the sculptor’s inability to control light was the reason why the medium could not modernize.

Rosso’s sensitivity to the effects of light on sculpture became evident after his arrival from Milan to Paris in 1889. He was the first sculptor to discover light as a physical and psychological force with its own emotional, responsive properties. During his years in Paris, Rosso gradually came to understand that light could become an important creative aspect of sculpture.

The world’s experience of light was transformed with the commercialization of Thomas Edison’s incandescent lightbulb in the early 1880s, which created new effects that could not be achieved by the softer gaslight of the past. New independent exhibition opportunities available in Paris from the 1880s onwards allowed sculptors to employ diverse lighting techniques and gain greater control over the lighting of their works.

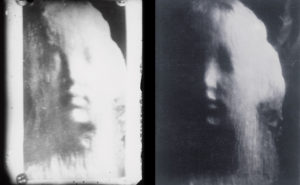

To create a stronger interpenetration between illumination and sculpture, Rosso broke up and manipulated the surfaces of his sculptures to make them more receptive to light and shadow. He even created a studio-foundry (where he set up a small do-it-yourself oven”) in Montmartre (in Paris) so that he could cast his own works and experiment with different surfaces. In this private space, he began to cast sculptures in wax as finished sculptures, as well as to manipulate his bronzes to elicit unusual effects. His wax casts seem particularly receptive to plays of light, since they give the illusion of something dissolving before our eyes. Rosso also began to obsessively photograph his own works in his studio under varied and unusual lighting conditions. The photographs that he took of his works display his sensitivity to plays of artificial and natural sources of illumination. He also experimented with curtains and special lighting effects during his exhibitions. In Rosso’s art, light does not create an overall caress of the work, as it does in the sculptures other artists, such as Auguste Rodin. Instead, Rosso’s use of light creates moments of visual and perceptual indeterminacy, making it hard for us to see the figures precisely, as if they were quickly moving in and out of sight.

A sculptor in the shadows

Despite his deep interest in light, for over a century, Rosso’s career and works have remained obscure in the histories of art, and this is why many people are still unfamiliar with his work. The German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe dubbed him the “Mephistopheles of sculpture” (Mephistopheles is a demon featured in German folklore) and other critics have wondered why his reputation was continually “eclipsed” by other sculptors of his time, such as his better-known rival Rodin. Rosso’s position at the margins of the history of modern sculpture was partly due to the difficulties he encountered as a foreigner working in Paris and the fact that he felt himself to be an outsider even back in Italy, his home country. Yet his contributions to modern sculpture were seen as fundamental by later sculptors such as Umberto Boccioni, Henry Moore, Constantin Brancusi, and Alberto Giacometti. Works like Ecce puer lead us to understand why Rosso’s discoveries about light and surface were crucial to these sculptors who came after him, and they continue to serve as vital inspiration for contemporary artists around the globe.

Medardo Rosso, Ecce puer (Behold the Child), 1906, bronze with plaster investment (private collection)

Notes:

[1] Ardengo Soffici, Medardo Rosso (Florence: Vallecchi, 1929), pp. 166–167

[2] Giovanni Lista, Medardo Rosso: Scultura e fotografia (Milan: 5 Continents, 2003), pp. 176.

[3] Max Kozloff, “The Equivocation of Medardo Rosso,” Art International 7 (December 5, 1963), pp. 46–47

[4] Our London Correspondence,” Manchester Courier, January 26, 1907. The phrase is from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s poem “A Sonnet” in the collection The House of Life (1870)

[5] Charles Baudelaire, “Why Sculpture Is a Bore,” in Baudelaire: Selected Writings on Art and Artists, trans. P. E. Charvet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972), p. 98; originally published as “Pourquoi la sculpture est ennuyeuse,” in Salon de 1846 (Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, 1846)

Additional resources

More on Medardo Rosso by Sharon Hecker

Medardo Rosso: Experiments in Light and Form (Pulitzer Arts Foundation)

Museo Medardo Rosso