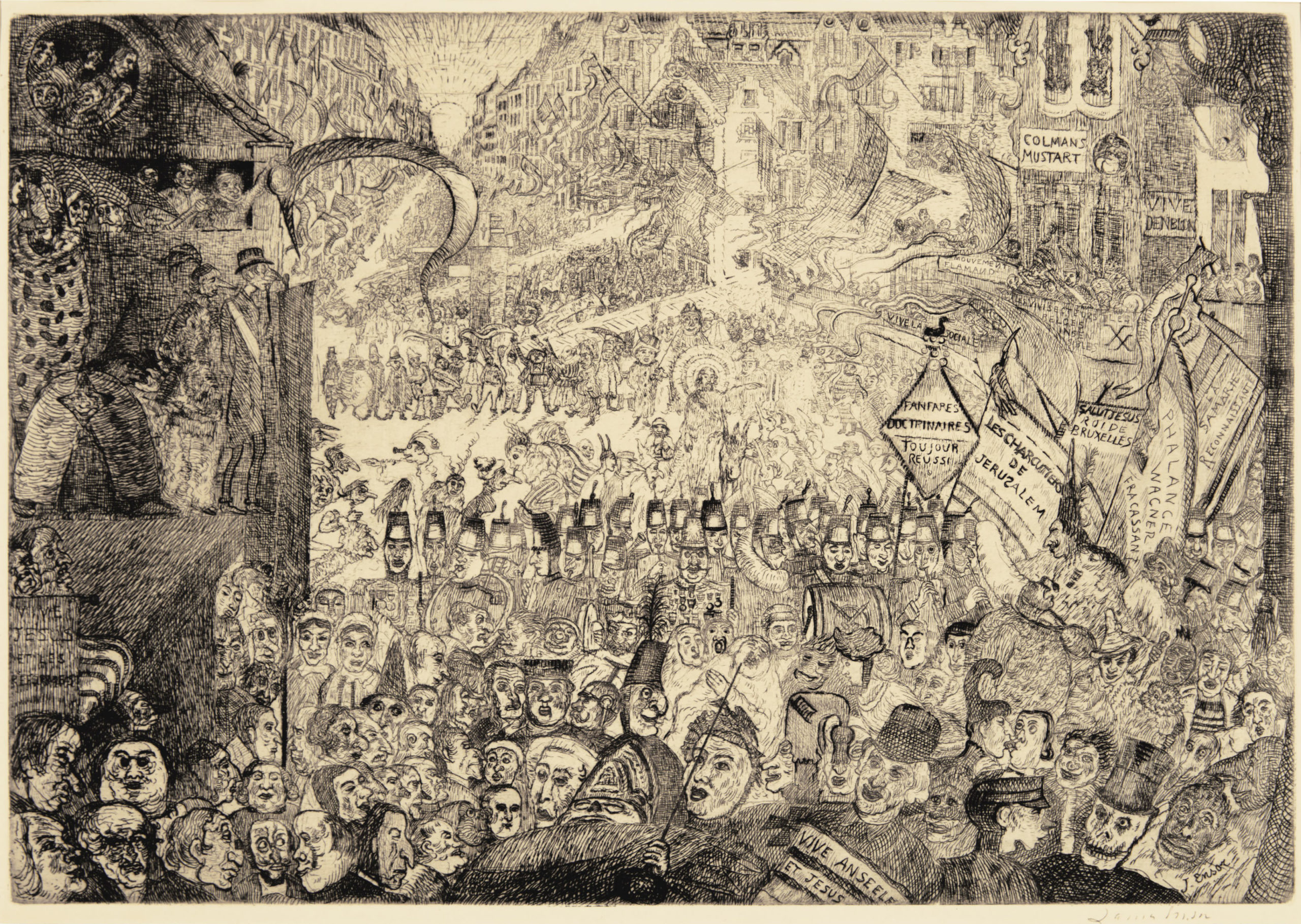

James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is one of the largest and most ambitious modern paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Over eight feet high and fourteen feet wide, it depicts a huge parade flooding down a wide street toward the viewer. The deep central space framed by reviewing stands and balconies suggests the stage of a proscenium theater. The lurid colors used to paint people, signs, and banners clash, and dozens of grotesque theatrical faces in the crowd, many wearing masks, compete for our attention. In the foreground the raucous mob threatens to spill out of the canvas and sweep us up into the chaos.

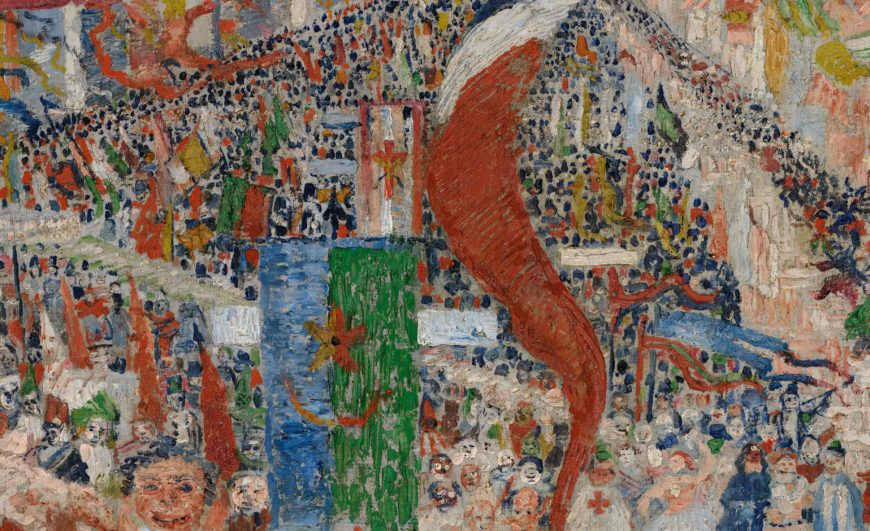

Crowds and banners (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, detail, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

The painting’s style and technique are as aggressive as its subject. The paint is applied in crude heavy strokes and slabs to create a rough, heavily-textured surface. Bright red dominates, and it is accompanied by its complement, green, as well as the other primaries blue and yellow. There is no shading, and the overall effect is flat and poster-like. The colors are brighter and lighter in the background, which sparkles with patterns of dots representing the distant crowds and rays of light that criss-cross the waving banners.

Humanity mocked

The painting’s title refers to the traditional subject of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, here transposed to contemporary Belgium. The painting is also reminiscent of the carnival parades of Mardi Gras, the Christian festival that precedes Lent. The small gold-haloed figure of Christ rides a donkey in the center of the painting’s upper portion behind the marching band. He is surrounded by a small group of masked figures whose long noses point up at him, and he raises his arm in a gesture of blessing. Most of the crowd, however, pays no attention to Christ.

Christ (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, detail, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Christ’s Entry into Brussels is far from being a conventional religious image of Christ as the savior of humanity. The painting mocks humanity, as well as human beliefs and institutions, both civic and religious. The grotesque parade is led by a bishop dressed in red with a gold miter who is marching out of the painting in the middle of the foreground.

Bishop (detail) James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

The sea of masks and faces behind him includes priests, government officials, soldiers, a military band preceded by a heavily-decorated leader, and caricatures of many types of ordinary citizens. A masked man dressed in the blue coat and white sash of the city’s mayor watches the parade from a reviewing stand on the right, accompanied by a group of elaborately-costumed masked figures. Ensor himself appears in profile as the yellow-clad figure in the tall conical red hat on the left.

Left: Self-portrait (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles); Right: Mayor on viewing stand (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Political critique or personal expression?

A red banner inscribed with the slogan “Vive la sociale” or “Long live the social [revolution]” stretches across the top of the painting and refers to contemporary politics and social reformers. Ensor’s sources for the painting included newspaper photos of an enormous socialist demonstration held in Brussels in 1886. The image of Christ had direct political significance as well; socialist politicians and writers in nineteenth-century France and Belgium frequently portrayed Christ as an exemplary social reformer who worked to improve the condition of the impoverished masses. Ensor is known to have been supportive of liberal social reforms and highly critical of powerful conservative institutions in Belgium, but Christ’s Entry into Brussels does not clearly support any particular political position. On the contrary, it seems to be a wholesale condemnation of both humanity and human ideologies.

Ensor created many works depicting scenes from the life of Christ, some of which were images of suffering in which he portrayed himself as Christ. These self-portraits display Ensor’s sense of persecution as an artist. Although he was a recognized leader among the Belgian avant-garde in the 1880s, he felt unfairly treated by critics and fellow artists. Some of his works were refused by Les XX, the Belgian avant-garde exhibition society he helped to found, and his anger and resentment are evident in many works.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels, a figure vomits on Les XX’s emblem painted in red on the green balcony above Ensor’s self-portrait.. Thus, among the many topics it addresses, the huge painting expresses Ensor’s personal bitterness toward the art world. It is also often interpreted as symbolically portraying the avant-garde artist as a Christ-like prophet misunderstood by the public.

Figure vomiting on the emblem of Les XX (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, detail, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

The northern tradition

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Procession to Calvary, 1564, oil on wood, 124.3 x 120.6 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Ensor painted Christ’s Entry into Brussels when he was twenty-eight. His earliest paintings were Realist and Impressionist in style and subject matter, but in the mid-1880s his work became increasingly idiosyncratic. He adopted subjects associated with prominent artists of the Northern Renaissance and Baroque tradition, including Bosch, Bruegel, Rembrandt, and Rubens. Christ’s Entry into Brussels echoes Bruegel’s Procession to Calvary, a painting in which Christ is also lost in a largely oblivious crowd.

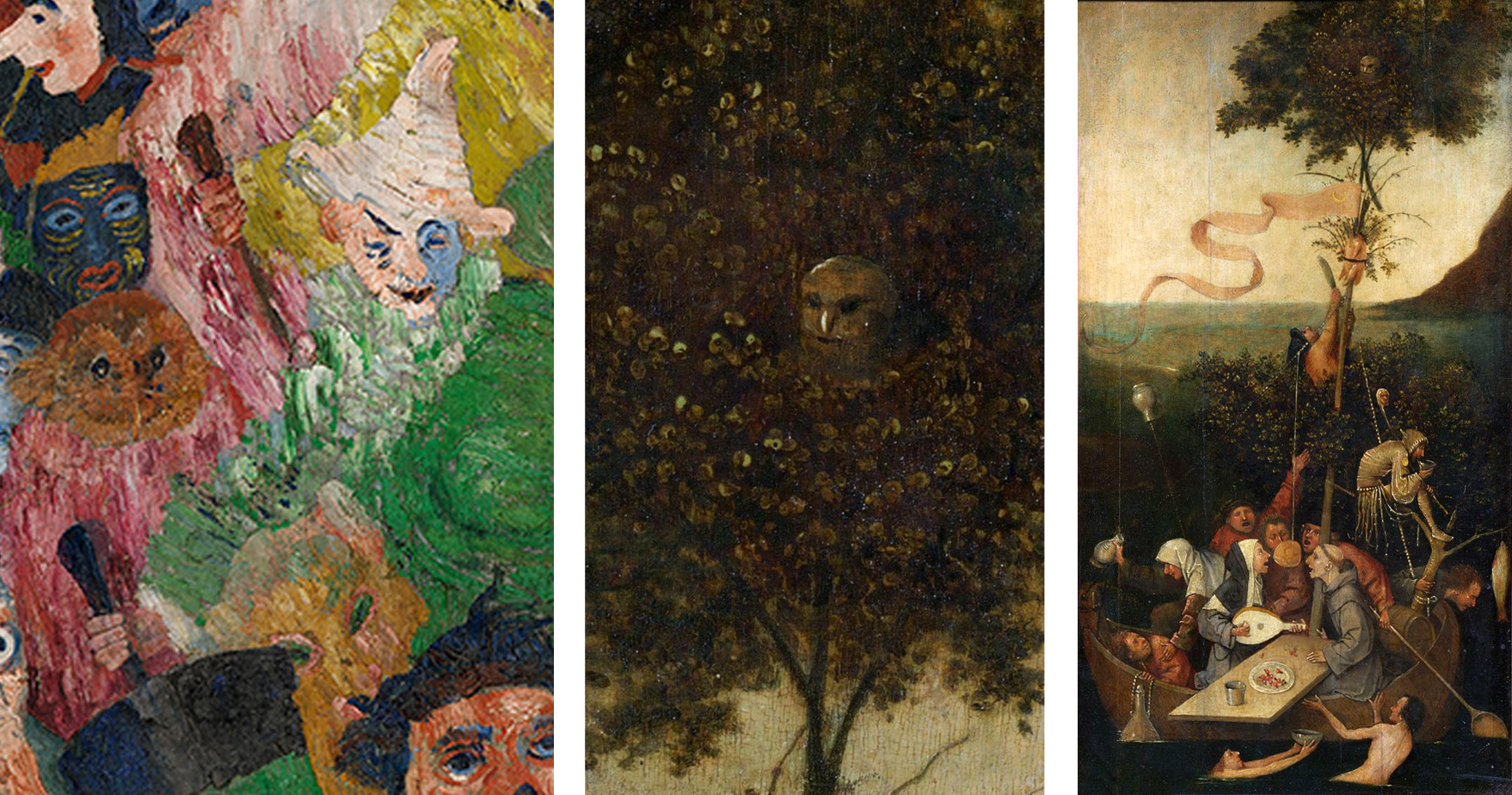

Left: Owl (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles); Center: Owl (detail) Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools, 1490-1500, oil on wood, 23 x 13 inches (Louvre, Paris) Right: Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools, 1490-1500, oil on wood, 23 x 13 inches (Louvre, Paris)

Ensor frequently borrowed fantastic figures and grotesque motifs from Northern Renaissance art, and like Bosch and Bruegel he reveled in the exposure of human folly. In his self-portrait in Christ’s Entry into Brussels Ensor extends his arm down towards the face of an owl, one of many faces in the crowd. While we now associate owls with wisdom, the owl is also a traditional symbol of foolishness. It appears often in this guise in Bosch’s paintings, including his Ship of Fools, where it peers out of the top of the tree.

Masks

The masks that are so prominent in Christ’s Entry into Brussels became a central subject for Ensor in the 1880s. His family owned a curiosity shop that sold papier-mâché Carnival masks in the seaside town of Ostend, making masks both personal and highly symbolic objects in Ensor’s work. Self Portrait with Masks shows him surrounded by a terrifying array of blindly staring masks, but his own portrait is also a sort of mask; it is directly modeled after self-portraits of the great Flemish Baroque painter Peter-Paul Rubens.

Left: James Ensor, Self Portrait with Masks, 1899, oil on canvas, 117 x 82 cm (Menard Art Museum, Komaki); Right: Peter Paul Rubens, Self Portrait, 1623, oil on panel, 85.7 x 62.2 cm (Buckingham Palace, Royal Collection, London)

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels even apparently unmasked figures have mask-like, caricatured faces suggesting that everyone wears some sort of mask. Ensor’s masked figures represent humanity as superficial, hypocritical, and grotesque. Masks also confer anonymity and allow people to act outside social laws without fear of being recognized and punished.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the theme of personal irresponsibility and freedom is enhanced by the association to a Carnival parade. During Carnival, society’s rules are dropped, and the usual social order is turned upside down; rich and poor switch roles, the beggar becomes king or queen for the day. Carnival is often described as serving as a sort of relief valve for the ordinary pressures of society, as well as a moment when underlying truths are exposed. In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the masks can be understood as revealing rather than hiding the true nature of humanity and human society.

Skeleton (detail), James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, detail, 1888, oil on canvas, 99 1/2 x 169 1/2 inches (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Skeletons

Skeletons were another central subject in Ensor’s art, and a skeleton figure wearing a top hat appears prominently in the lower left of Christ’s Entry into Brussels. It adds a macabre reminder of death’s presence in the midst of life, a traditional artistic theme known as memento mori that was very popular in Northern Baroque painting. In numerous works Ensor portrayed skeletons and masked figures in enigmatic scenes that mock the foolishness and cruelty of human behavior. Ensor’s skeletons frequently represent art critics persecuting him.

In Skeletons Fighting over a Hanged Man two skeletons wearing elaborate costumes duel over mannequins using a mop and broom for weapons. Masked figures carrying knives push through the doorways and seem to menace the duelists on both sides. In the left foreground, a third skeleton watches the combat with paintbrush in hand and a palette on his lap, reminding us that for Ensor his paintbrush was both his weapon and his claim to immortality.

James Ensor, Skeletons Fighting over a Hanged Man, 1891, oil on canvas mounted on panel, 23 ¼ x 29 1/8 inches (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp)

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is an ambitious and idiosyncratic painting that enlists multiple historical and contemporary artistic sources to address topics that range from the personal to broad social concerns. It was not publicly exhibited until 1929, but prints of it were widely circulated, and Ensor’s highly individualized art influenced many later modern artists, most notably those associated with Expressionism.