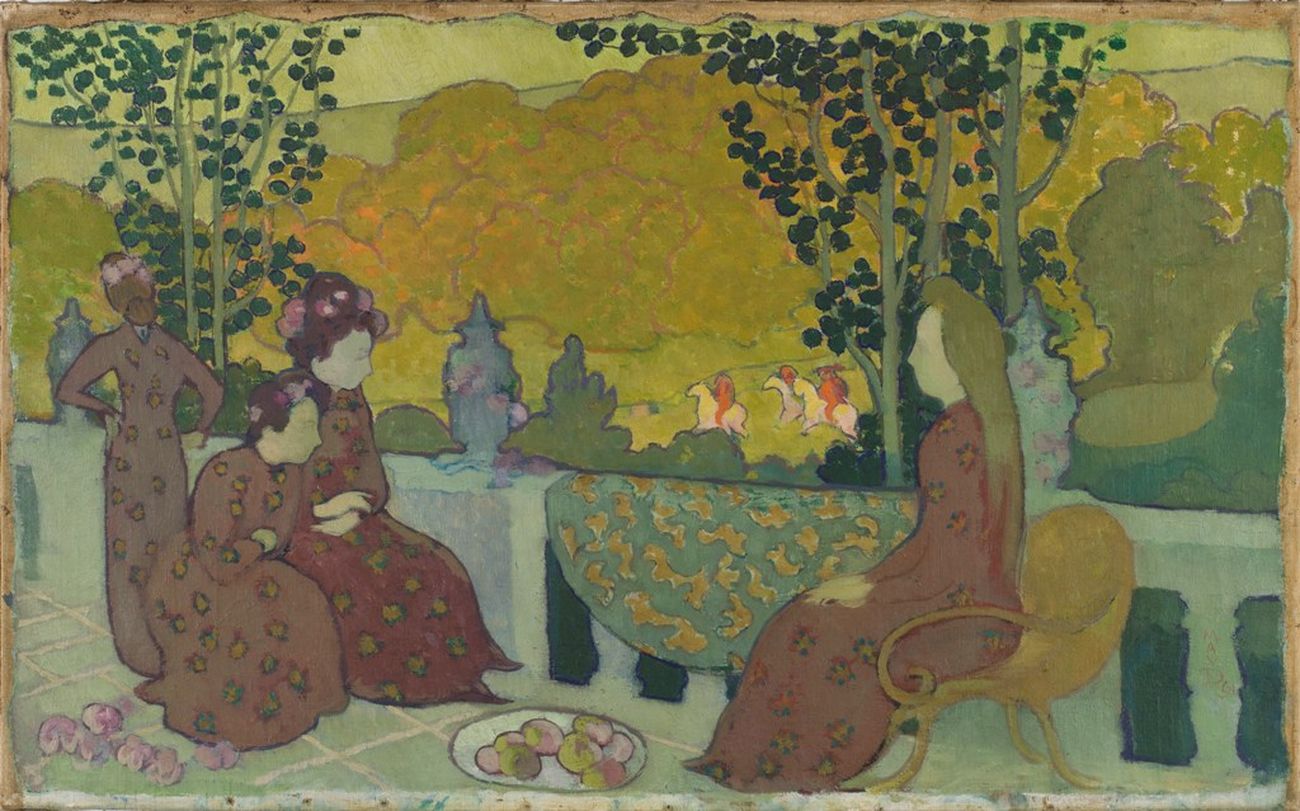

Édouard Vuillard, Public Gardens, 1894, distemper on canvas, 213.5 x 308 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

In 1894 the Nabi painter Édouard Vuillard decorated the living room of a Paris mansion with nine paintings depicting children and their nannies in the park. The three panels shown here form a symmetrical group in the traditional triptych format of an altarpiece, with two tall vertical panels framing a wider central panel. They present a single continuous view connected by a horizontal fence and distant forest.

In the foreground the composition is strongly asymmetrical, with most of the figures crammed into the left panel. Diagonals created by the painted patterns of light and shade on the ground enhance the dynamic asymmetry of the painting. The people form points of interest surrounding the empty expanse of sandy gravel in the center. Variegated patterns of foliage, clothing, and clouds are scattered across the paintings’ surfaces, while patches of flat color punctuate the composition and serve as visual anchors.

Abstract decorative forms

Vuillard’s emphasis on flat patterns and design is typical of Nabi painters, who embraced the implications of Maurice Denis’ statement: “A painting — before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote — is essentially a flat surface covered with colors arranged in a certain order.”[1] Nabi paintings do not allow viewers to get lost in the represented scene and forget that they are looking at colors applied to a surface. Instead, they display the tension between the represented scene and the paint that creates it by emphasizing abstract decorative forms over naturalistic details.

Maurice Denis, April (Panel for a young girl’s room), 1892, oil on canvas, 38 x 61.3 cm (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo)

In Maurice Denis’ April the landscape and figures are reduced to simple shapes, and the colors are flat and unmodulated. Denis further emphasizes the surface of the picture plane by depicting the distant hills in red tones rather than fading blues to represent the effect of atmospheric perspective.

A decorative arts tradition

April was made specifically to decorate a young girl’s room, and many Nabi paintings were designed as ensembles for specific locations. The seven-foot-tall panels of Vuillard’s Public Gardens created a wallpaper-like backdrop for a family’s living room. This integration of representational paintings into the decorative scheme of a room was markedly different from the conventional manner of framing paintings as if they were windows onto another world.

Germaine Boffrand, Salon de la Princesse, Hotel de Soubise, Paris, 1735 (photo: NonOmnisMoriar, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In embracing decorative painting the Nabis were participating in a well-established French tradition of decorative arts and luxurious artisanal production. During the eighteenth century Rococo paintings were designed as components of multi-media decorative ensembles for aristocratic salons, such as the Salon de la Princesse in the Hôtel de Soubise. In the nineteenth century the most prominent decorative paintings were murals in public buildings. The classicizing public murals of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes were admired by the Nabis as well as by many other Post-Impressionist and Symbolist artists.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, The Sacred Wood, mural in the Grand Amphitheater of the Sorbonne, Paris (photo: Sigoise, CC BY-SA 3.0)

They appreciated the suggestive qualities of Puvis’ dream-like images of introspective figures as well as his simplified forms and colors. Puvis’ limited range of muted pastel colors imitated the qualities of Italian Renaissance frescoes, and enhanced the flat decorative qualities of his paintings by softening contrasts and eliminating details. The Nabi painters adapted Puvis’ decorative approach to modern subject matter and used painting techniques that reflected the innovations of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in their bright colors, visible brushwork, and surface patterns.

The influence of Japanese art

Kano Koi, Blossoming Plum and Camellia in a Garden Landscape, Edo Period, ink, color and gold on paper, 167.9 x 382 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Washington)

The Nabis were also greatly influenced by Japanese art and design in their compositions as well as in their engagement with the decorative arts. Pierre Bonnard used the popular Japanese format of multi-panel folding screens for a number of works, including Nannies’ Promenade.

Pierre Bonnard, Nannies’ Promenade, Frieze of Carriages, 1899, color lithograph, each panel 137.2 x 47.6 cm (MoMA)

Like Vuillard’s Public Gardens, Bonnard’s screen is both representational and decorative. The subject of the works is similar, a modern scene of nannies and children, and in both works the asymmetrical composition spreads across several panels with the overall emphasis on flat patterns and ornamental design.

Designing for life

Paul Ranson, Rabbits, c. 1893, distemper on paper, design for wall paper, 23 5/8 x 29 ½ inches (Phillips Collection, Washington)

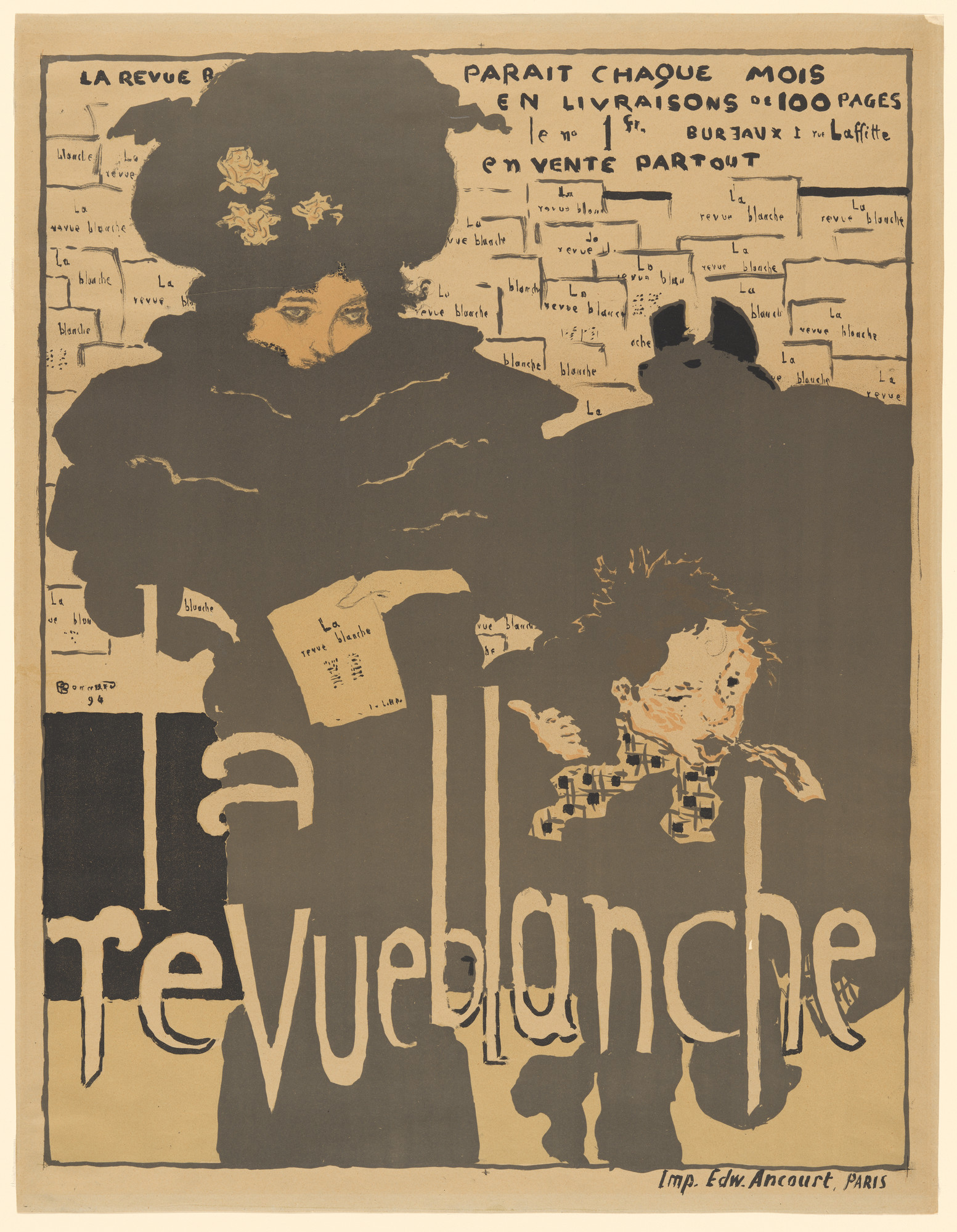

The Nabis’ embrace of the decorative arts was wide-ranging and included designs for wallpaper, tapestries, stained glass, and ceramics. They illustrated books, created posters, and designed costumes and sets for Symbolist theatrical productions. Pierre Bonnard’s poster for the Symbolist literary journal La Revue Blanche adapts the Nabi style of flat patterns and decorative design to the print medium of color lithography.

Pierre Bonnard, La Revue Blanche, 1894, lithograph, 80.7 x 61.9 cm (MoMA)

Through their many forms of artistic production the Nabis expanded art into all areas of life. This was a widely-shared goal among fin-de-siècle artists and designers, particularly those involved with the international movement known in France as Art Nouveau.

Ker-Xavier Roussel, The Garden, 1894, stained glass executed by Tiffany and Co., 48 7/8 x 36 5/8 inches (Phillips Collection, Washington)

The Nabis were closely associated with Art Nouveau through the art dealer Siegfried Bing, a leading promoter of both Art Nouveau and Japonisme. Bing exhibited Nabi art in his Paris gallery and commissioned work from them, including designs for stained glass windows to be made by Louis Comfort Tiffany’s American company.

Édouard Vuillard, The Chestnut Trees, 1895, distemper on cardboard, 110 x 70 cm (Dallas Museum of Art) Design for Tiffany window

The Nabis exhibited as a group through the 1890s. Their formalist approach to painting influenced many later modern painters, most notably the Fauves in the early 1900s. The Nabis also contributed to modernism’s breakdown of the traditional value distinctions between the fine and decorative arts. Their wide-ranging work in a variety of media was part of a trend in art and design that encompasses the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau in the nineteenth century and Russian Constructivism and the Bauhaus in the twentieth century.