Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm (Musée Marmottan, Paris)

Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in an embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.Louis Leroy, “Exhibition des Impressionnistes,” Le Charivari (25 April 1874), as translated in John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (1946)

The bright, burning orange sun rises in the distance, casting rays of light across a calm morning in the Port of Le Havre. The rippling waters of the port’s inlet create small waves that anticipate the day’s activity. Three fishing boats float into the distance, where construction of a dock is visible through the morning mist. The cool blue, green, and white hues dominating the landscape are interrupted by the sunlight that radiates across the water.

Industry and global exchange

Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise is best known for being the painting that established Impressionism as a new movement in art history, as it shocked critics who first saw it in an 1874 exhibition in Paris.

On the surface, the painting appears to capture a quiet morning at Le Havre, but a closer look offers insight into its context. The painting’s material, technique, and subject matter reflects the influence of modernity on artmaking at this time, and also highlights trade networks between France and Japan that gained momentum in the 1860s and 1870s. Monet’s Impression, Sunrise is not only an engaging study of the effects of light and color, but it also reveals a changing world of industry and global exchange in 19th-century France.

A postcard of the Norman port of Le Havre from around 1900, with the white Hôtel de l’Amirauté (where Monet painted Impression, Sunrise) at the center (Bibliothèque municipale du Havre)

Modernity en plein air

Monet’s painting was made shortly after he returned to France from London, where he lived for two years to avoid the Franco-Prussian War. Impression, Sunrise was one of several paintings Monet made during his visit to Le Havre, a major port city in Northern France where he spent most of his childhood. Although the perspective of the scene indicates that Monet painted from his window at the Hôtel de l’Amirauté, the painting captured the fleeting effect of a sunrise on the water.

The misty sky over Le Havre (detail), Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm (Musée Marmottan, Paris)

The expressive movement of Monet’s brush is evident in the streaks of orange, red, pink, gray, blue, and white pigment that blend together to form the misty sky over Le Havre. These painterly brushstrokes reflect a new technique called en plein air (“in open air”), which gained popularity in the 1860s. Artists that worked in this style left their studios to paint outdoors, using rapid brushstrokes to quickly capture the effect of light and color on the atmosphere.

Although Impression, Sunrise was painted in a room overlooking the port, Monet had started experimenting with the plein air technique by 1872, and an 1885 painting by John Singer Sargent shows him painting in this style.

John Singer Sargent, Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood, 1885, oil on canvas, 54 x 64.8 cm (Tate, London)

The palette in Monet’s left hand is loaded with fresh paint that he carried with him to this destination. He leans forward to add more pigment to the canvas on his easel, which is turned toward the viewer to reveal a loosely painted landscape. Sargent’s rendering also embraced plein air painting, as the artist worked quickly to capture his friend.

Artists who painted en plein air were influenced by new tools for art-making that developed as a result of the Industrial Revolution. John Rand’s collapsible paint tube, for example, changed the way paint could be stored. For centuries, artists had preserved their expensive pigments in pig’s bladders, but they were unable to be sealed, which meant that paint was sometimes wasted. The collapsible paint tube not only solved this problem because artists could open and close them with a cap, but they also improved the portability of materials. The canvases they painted out in the world were no longer preliminary sketches or studies, but the finished work of art.

Fleeting moments in paint and print

Monet’s composition for Impression, Sunrise was influenced by his interest in and collection of Japanese prints. Prior to 1853 (and for 200 years), Japan had been isolated from the rest of the world. In 1853, American warships were sent on a mission to Tokyo Harbor to pressure Japan to open trade negotiations with the United States and Europe. Japanese prints, fabrics, ceramics, and other art materials flooded European and American shops, and were snatched up by collectors looking for the latest fashionable items.

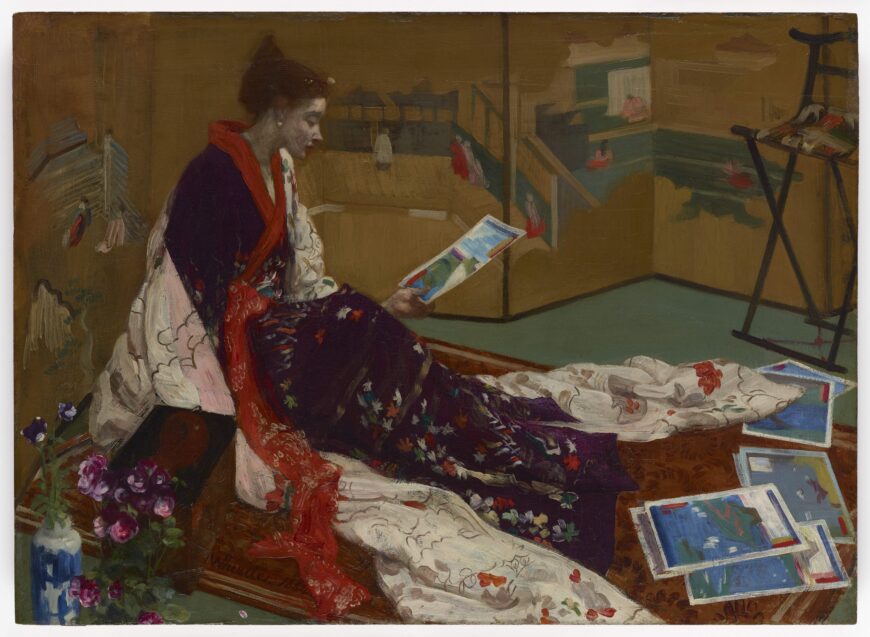

James McNeill Whistler, Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen, 1864, oil on wood panel, 50.1 x 68.5 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, D.C.)

James Whistler’s Caprice in Purple and Gold depicts a model dressed in a kimono gazing at a collection of prints. Whistler’s painting reflects the prevalence of japonisme, a term that describes the Euro-American fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics at this period. The folding screen creates the impression of a flattened background, which evokes the flatness and closely-cropped compositions of Japanese ukiyo-e prints.

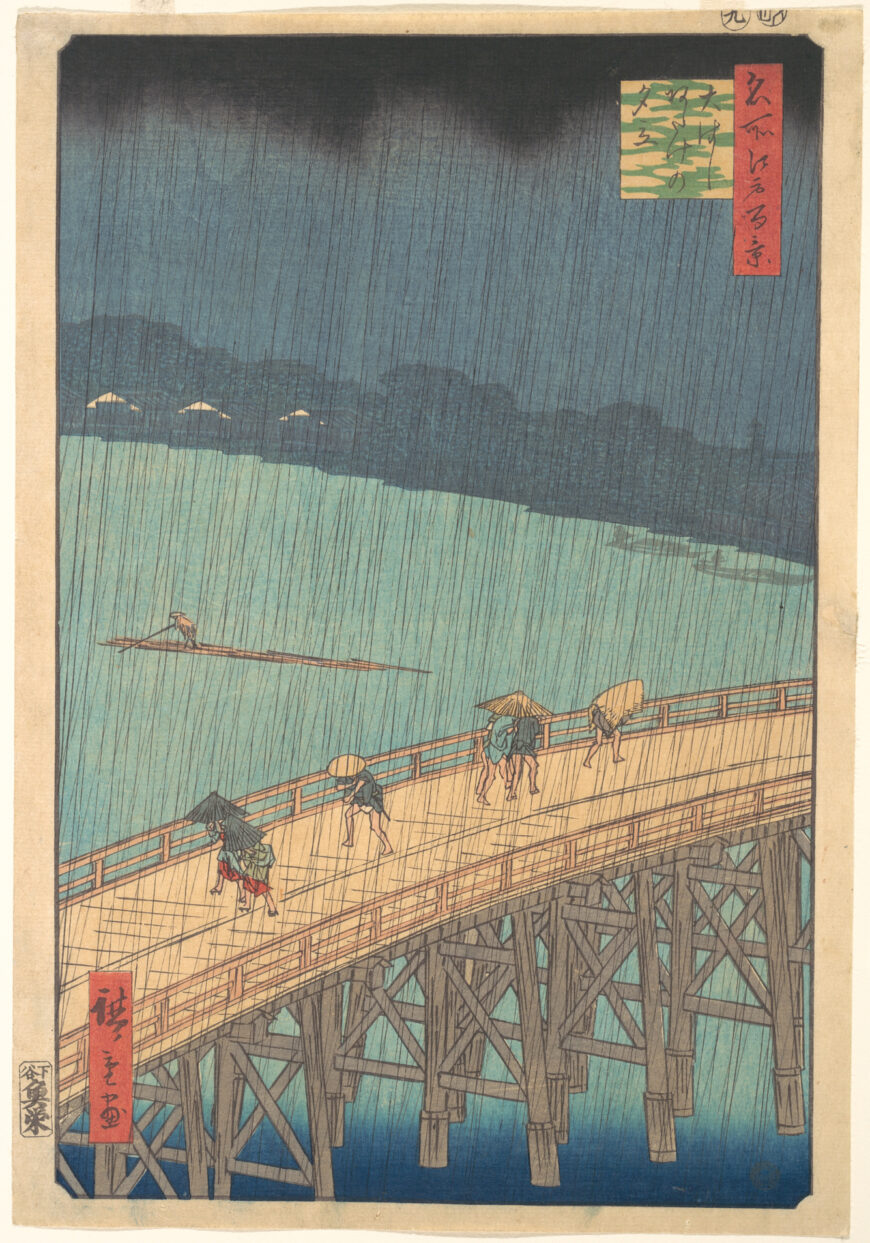

Utagawa Hiroshige, Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, woodblock print, ink and color on paper, 34 x 24.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Claude Monet started building his own collection of Japanese prints in the 1860s. A famous work in his collection was Utagawa Hiroshige’s “Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake.” Hiroshige’s scene captures a view of the Sumida River during a torrential downpour. People crossing the bridge in the foreground duck under parasols, hats, and blankets to protect themselves from the rain. Through the streaks of rain, a single figure is on the river, guiding their boat through the water. Hiroshige’s scene is closely cropped, giving the viewer a diagonal viewpoint toward the river. The artist uses varying shades of blue to show the sky, distant shore, and river, and dark lines create the impression of moving water and pouring rain.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm (Musée Marmottan, Paris)

Impression, Sunrise uses several techniques employed in Sudden Shower, indicating that Monet borrowed from Hiroshige’s print. Instead of using traditional techniques like linear perspective, Monet painted three boats at the center of the work to produce a diagonal line that implies receding space. The sky and water are only distinguishable from each other through the shadowy dock (the Quai au Bois) that stretches from one side of the painting to the other. The painterly brushwork creates an impression of flatness. Hiroshige and Monet both use a cool color palette to evoke the essence of a moment: whereas Hiroshige’s scene shows the power of the yūdachi, a powerful rainfall that darkened the daytime skies, Monet depicts the calm, misty start to a busy day at the sea port.

Industry and trade at the Port of Le Havre

Although Impression, Sunrise was neither Monet’s first, nor his only painting to feature Le Havre, it captures a period of growth for the port, indicative of France’s participation in global trade and commerce. In the 18th century, Le Havre underwent its first major expansion to increase France’s participation in the slave trade, and by the 19th century, it was rebuilt several times to meet the needs of a newly industrialized nation.

Eugène Louis Boudin, Port of Le Havre, 1887, oil on canvas, 65.4 cm. x 90.5 cm (Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick)

Eugène Louis Boudin’s 1887 painting shows Le Havre on a busy day, with boats making their way across the harbor as ships enter to escape the storm clouds billowing in the distance. The dock on the right side of the painting is filled with workers who have already unloaded a ship.

Monet painted several scenes of the port between 1865 and 1880, and they reveal the way that his style and technique developed over time. His 1867 painting of Le Havre shows a busy port scene en plein air, with several shades of green and white to indicate the motion of churning waves. By 1872, Monet had embraced singular, horizontal strokes of dark blue to imply the water’s movement in Impression, Sunrise.

Claude Monet, The Entrance to the Port of Le Havre (formerly The Entrance to the Port of Honfleur), c. 1867–68, oil on canvas, 50.2 x 61.3 cm (Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena)

As he painted Impression, Sunrise, the Quai au Bois was being reconstructed as part of a larger project to widen Le Havre’s entrance, and Monet emphasized this industrial progress in the form of cranes silhouetted against the morning sky. In another 1872 painting, Le Havre: Night Effect, Monet painted the same scene at night. Its predominant shades of black, blue, and gray are interrupted by touches of white, yellow, and red.

Claude Monet, The Port of Le Havre, Night Effect, 1872, oil on canvas, 60 x 81 cm (Museum Barberini, Potsdam)

Monet’s painterly technique used in the 1872 scenes of Le Havre visually evoked the transitory nature of port life in the 1860s and 70s: it highlights the constant ebb and flow of trade, commerce, and nature. Both paintings are recognizable in that they depict an identifiable subject—but their surfaces have been dematerialized. Monet’s painting is a collection of brushstrokes on a canvas support. It is not a representation of a sunrise but an impression of one.

“A Revolution in Painting!”

On April 15, 1874, eager visitors gathered in a studio on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris to view one hundred and sixty-five works by members of the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers. The exhibition took place in a private studio owned by the photographer Nadar, and represented a significant moment in the Parisian art world. The 1874 show highlighted a broad range of artworks that defied the rigid categories embraced by the traditional art world, and Impression, Sunrise was among the most notable of them.

The exhibition marked a public rejection of the Salon system in Paris, and established itself as independent from other official spaces dedicated to art. Although smaller venues existed in which artists could show their work, the Salon had been the primary venue for exhibiting since the 17th century. In the second half of the 19th century, artists more frequently showed their work in spaces free from the constraints of the Salon—but this traditional venue continued to wield significant power in the art world. Although the 1874 show is commonly referred to as “the first Impressionist exhibition,” it was populated by artists who worked in a variety of styles and formats. They consciously departed from Salon practices by hanging their works in two rows so that visitors could clearly see all of them.

Monet exhibited five paintings and seven pastels at the show. Impression, Sunrise captured the attention of critics who were shocked by the work’s sketchiness. In his review of the 1874 show, Louis Leroy disparaged Monet’s painting by comparing it to “wallpaper,” implying that the work had no value or purpose beyond decoration. [1]

Monet’s loose brushwork and the subject matter of a modern working port did not reflect the traditional characteristics for high art. It does not depict the mythological or battle scenes embraced by French history paintings, nor does it express an overt moral or political message. Instead, it captures a fleeting moment in time using rapid brushwork and bright colors.

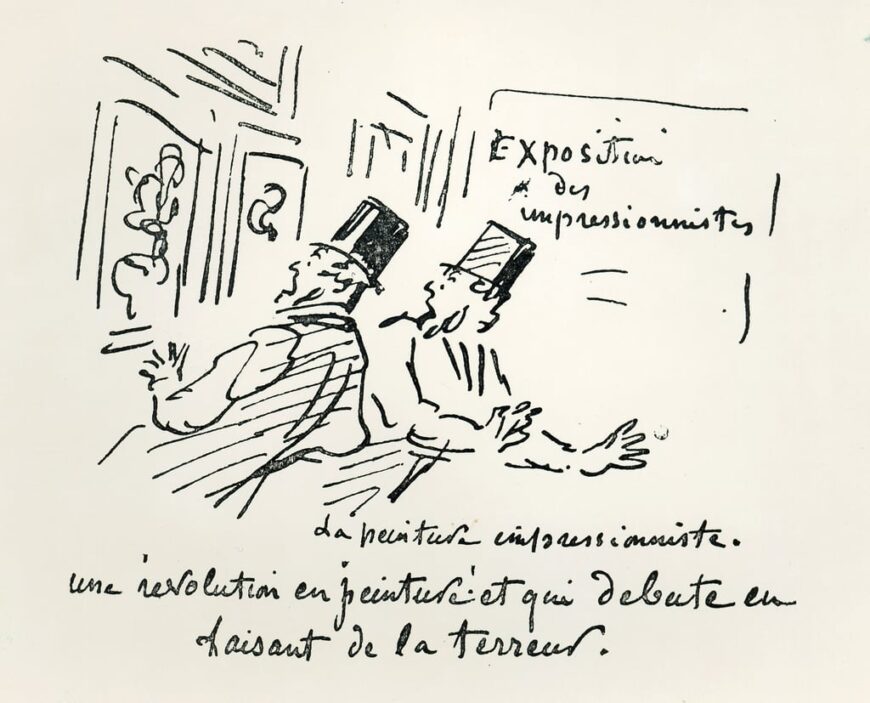

Cham (Amedee Charles Henri de Noe), Caricature of the first Impressionist Exhibition in Paris, “Revolution in Painting! And a terrorizing beginning,” 1874, engraving (Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris)

An 1874 cartoon depicts men gasping in horror at the framed paintings in the show. The curved lines on the canvases implies that they are painted en plein air. One figure exclaims, “A Revolution in Painting! And a terrorizing beginning.” Other visitors to the exhibition celebrated Monet’s work for its modern characteristics. Jules-Antoine Castagnary emphasized his ability to capture a subject using an innovative technique, arguing that it depicted “not a landscape, but the sensation produced by a landscape.” [2]

On the surface, Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise captures a quiet morning in the port of Le Havre, but a closer look at the work offers insight into many changes taking place in 19th-century Europe. Monet’s work depicts a moment of growth for the port, indicative of France’s participation in global trade and commerce. Moreover, its flattened composition not only reflects Monet’s embrace of new, industrial art materials, but also provides insight into the artist’s collection and study of Japanese prints. Monet’s inclusion of this work in the 1874 exhibition reveals a new moment of painting that departs from past traditions.

Notes:

[1] “Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in an embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.” Louis Leroy, “Exhibition des Impressionnistes,” published in Le Charivari (25 April 1874), translated in John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1946 and reproduced on Artchive).

[2] “These are everyone’s personal notes. The common concept which unites them as a group and gives them a collective strength in the midst of our crumbling epoch is the determination not to search for a smooth execution, but to be satisfied with a general aspect. Once the impression is captured, they declare their work is done. The adjective Japonais, which was first applied to them, was meaningless. If one wants to characterize them with a single word that explains their efforts, one would have to create the new term of ‘Impressionists.’ They are Impressionists in the sense that they render not a landscape but the sensation produced by a landscape. This very word has entered their language: not landscape but impression, in the title given in the catalogue for Mr. Monet’s Sunrise. From this point of view, they have left reality behind for a realm of pure idealism.” Jules-Antoine Castagnary, exhibition review, Le Siècle (April 29, 1874), reproduced in Monet’s Impression Sunrise: The Biography of a Painting (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2014), p. 19.

Additional resources

This painting at the Musée Marmottan

Port of Le Havre History from the Territorial Department of Le Havre

Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886 (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1996).

Karin Breuer, Japanesque: The Japanese Print in the Era of Impressionism (New York: Prestel, 2010).

Heinrich Christoph, Claude Monet: Capturing the Ever-Changing Face of Reality (Los Angeles: Taschen, 2015).

Christine M. E. Guth, Alicia Volk, and Emiko Yamanashi, Japan and Paris: Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the Modern Era (Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2004).

Nina Nikolaevna Kalitina, Claude Monet (New York: Parkstone Press International, 2011).

Marianne Mathieu and Dominique Lobstein, editors, Monet’s Impression Sunrise: The Biography of a Painting (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2014).

Catherine Morris, The Essential Claude Monet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999).

Martha Ward, “Impressionist Installations and Private Exhibitions,” The Art Bulletin, volume 74, number 4 (1991), pp. 599–622.

Heinz Widauer, et al., Claude Monet: A Floating World (Vienna: The Albertina Museum, 2018).