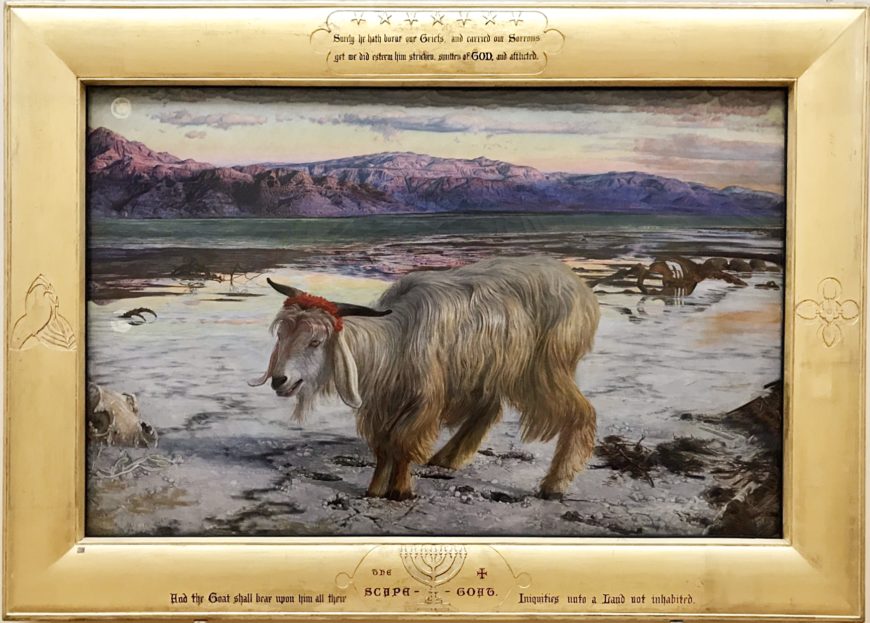

William Holman Hunt, The Scapegoat, 1854–1856, oil on canvas, 86 × 140 cm (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight)

William Holman Hunt, London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company albumen carte-de-visite, c. 1865 8.9 x 5.7 cm (National Portrait Gallery, London)

In 1854 William Holman Hunt traveled to Jerusalem and the area around the Dead Sea in search of inspiration for religious subjects. Hunt, who was himself a deeply religious man, considered a trip to the land of Christ’s birth essential for the creation of religious painting. He was one of the strictest adherents to the belief in “truth to nature,” the idea that artists look to the visible world directly when they paint (an idea that was central to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—a group that included Hunt). The area around the Holy Land was increasing popular as a tourist destination due to its Biblical associations and the many archaeological excavations being conducted by Europeans and Americans due to their colonial connections to this part of the globe.

At the time, a trip to the Dead Sea was very dangerous. According to a later account by the artist, “the whole country to the south of Jerusalem had become disturbed …each day brought worse tidings, and I was strongly urged to postpone a project of going to stay at so remote a spot.” [1] Hunt was undeterred and by the time he returned to England he had created a series of paintings that challenged his contemporaries. The most unusual of these was The Scapegoat, a picture that was greeted with confusion when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856.

The subject

As described in the Book of Leviticus (in the Hebrew Bible), one white goat was sacrificed in the temple, while another was sent into the wilderness to carry away the sins of mankind. The picture illustrates a tradition from the The Talmud carried out on the annual Day of Atonement. A red filet of beef, which was supposed to turn white after the sins were washed clean, was tied to the animal’s horns before it was sent into the desert to illustrate the words of Isaiah 1:18 “Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow.”

Remarkable in its stark reality, The Scapegoat is a meticulous exercise in both landscape and animal painting. The shaggy coat of the lone goat is so minutely detailed that the viewer can almost feel the texture. Head lowered, the goat stares out of the canvas, its eyes rolled upwards towards heaven, clearly exhausted and uncomfortable in the inhospitable surroundings. Its hooves crunch through the salt encrusted ground, and the skeletal remains of other creatures point to the ultimate end awaiting this unfortunate animal. In contrast to the bleak foreground, the distant mountains and beautifully colored sky beckon the viewer, while still serving as a metaphor for the imminent death of the goat. The religious symbolism of the painting also looks to the New Testament, as in Hunt’s view the goat is also a reminder of the fate of Christ, who died for the sins of mankind. To emphasize this connection to the goat, rather than the lamb most commonly associated with Christ, the artist created a specially designed gold frame inscribed with two Biblical quotations: “Surely he hath borne out Griefs and carried our Sorrows; Yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of GOD and afflicted (Isaiah 53:4) and “And the Goat shall bear upon him all their iniquities unto a Land not inhabited (Leviticus 16:22). Both of these Old Testament verses can be interpreted as foreshadowing Christ’s sacrifice.

The difficulties of painting from life

Detail, William Holman Hunt, The Scapegoat, 1854–1856, oil on canvas, 86 × 140 cm (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight)

Hunt also traveled into the wilderness to create the picture. In October of 1854, he visited the Dead Sea with a party of Englishman and decided that this unusual place, with its low elevation and high level of salt content, was the perfect backdrop for the painting he had in mind. He returned in November of the same year, this time with only Arab companions even though his command of their language was rudimentary at best, which isolated Hunt from his traveling companions and those he encountered in his travels. They camped at a place called Oosdomm, which had recently been proposed as the site of Sodom, the biblical city destroyed due to its evil ways. Hunt spent 17 days going back and forth between the camp and the setting of his painting, about a 2-mile trek, carrying his canvas. The area was considered quite dangerous and in letters home and his journal, Hunt recounts more than one occasion where he was placed in a potentially hazardous situation, such as when he was pelted by stones, hitting both the artist and his horse. [2] In an effort to speed up and vacate the area, Hunt even worked on the Sabbath, something the religious artist did not normally do.

The goat proved to be another difficulty for the painter. Apparently, he took a rare white goat with him on his expedition, although it is unclear whether or not he actually took it with him on his daily treks from the camp to the actual site. While several drawings of the goat done at the time exist, the goat is not mentioned in Hunt’s Journal until after his return to Jerusalem when he records that the goat was ill. Eventually the goat died, providing more hardship in finishing the painting as white goats were both rare and expensive. The replacement goat posed in his studio surrounded by rocks, mud, and crusty salt brought back from the site.

The painting’s reception

On Hunt’s return to England after his journey to the Holy Land, audiences were unsure of how to interpret The Scapegoat. Was it a work of profound religious significance or just an unusual animal picture? Hunt tried to emphasize the religious nature of his subject by including two Biblical quotations carved into the picture’s frame: “Surely he hath borne our Griefs and carried our Sorrows; Yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of GOD and afflicted” (Isaiah 53:4) and “And the Goat shall bear upon him all their iniquities unto a Land not inhabited” (Leviticus 16:22).

William Holman Hunt, The Scapegoat, 1854–1856, oil on canvas, 86 × 140 cm (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight)

Even if some were unsure of the meaning of the picture, no one could deny the mastery of both subject and execution. Hunt’s friend Ford Madox Brown wrote in his diary “Hunt’s Scapegoat requires to be seen to be believed in. Only then, can it be understood how, by the might of genius, out of an old goat, and some saline encrustations, can be made one of the most tragic and impressive works in the annals of art.” [3] In The Scapegoat Hunt created one of the most unusual paintings of the Victorian period, a blend of detail and realism typical of Pre-Raphaelite artists and the religious spirit of a deeply devout artist.

Notes

- William Holman Hunt, “Painting, ‘The Scapegoat’” The Contemporary Review Vol. LII, 1887, p. 21.

- William Holman Hunt, “Painting, ‘The Scapegoat’” The Contemporary Review Vol. LII, 1887, p. 23.

- Virginia Surtees, ed, The Diary of Ford Madox Brown (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), p. 174.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Lady Lever Art Gallery

George Landow, Replete with Meaning: William Holman Hunt and Typological Symbolism

The Scapegoat on the Frame Blog