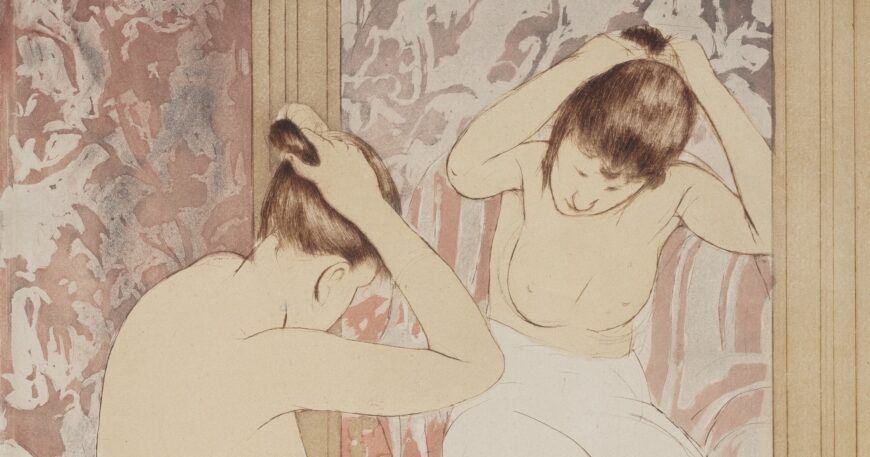

Mary Cassatt, The Coiffure, 1890–91, color drypoint and aquatint on laid paper, 43.2 x 30.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Kitagawa Utamaro, Two Young Women Kneeling Back to Back, Dressing Their Hair in Mirrors, woodblock print (Leiber Collection, New York)

In April of 1890, the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris showcased an exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints. These ukiyo-e images, “pictures of the floating world,” as they were evocatively called, were comprised mostly of scenes of urban bourgeois pleasure—geishas, beautiful women, sumo wrestlers, kabuki actors—and pictures of the natural beauty around Edo (present day Tokyo)—the mists of Mount Fuji, cherry blossoms, rain showers, and surging waves along the port of Kanagawa.

Ever since Commodore Matthew C. Perry helped to open imperial Japan to Western trade in 1853, Europe had become fascinated with Japanese culture. Artists like Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet (recall Monet’s Japanese bridge in his gardens at his estate in Giverny), Vincent van Gogh, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, were among the many who incorporated elements of Japanese design into their work. Some of them also frequented the bustling antique shop on the Rue de Rivoli, La Porte Chinoise, that specialized in Japanese woodblock prints, jades, lacquers, and porcelains. The craze of Japonisme went to such heights that in 1885, the English opera team of W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan staged their most popular show, a comic opera set entirely in imperial Japan, The Mikado.

Among the audience at the exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts that April was the American expatriate painter, Mary Cassatt. Cassatt’s close friend, Edgar Degas, was a great admirer of Japanese art and had recently seen the exhibition with Camille Pissaro. Cassatt was spellbound. In a letter written that week to her friend, the painter Berthe Morisot, she wrote, “You who want to make color prints wouldn’t dream of anything more beautiful. I dream of doing it myself and can’t think of anything else but color on copper…P.S. You must see the Japanese—come as soon as you can.” [1]

Kitagawa Utamaro, Takashima Ohisa Using Two Mirrors to Observe Her Coiffure, c. 1795, woodblock print, ink and color on paper, 36.3 x 25 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

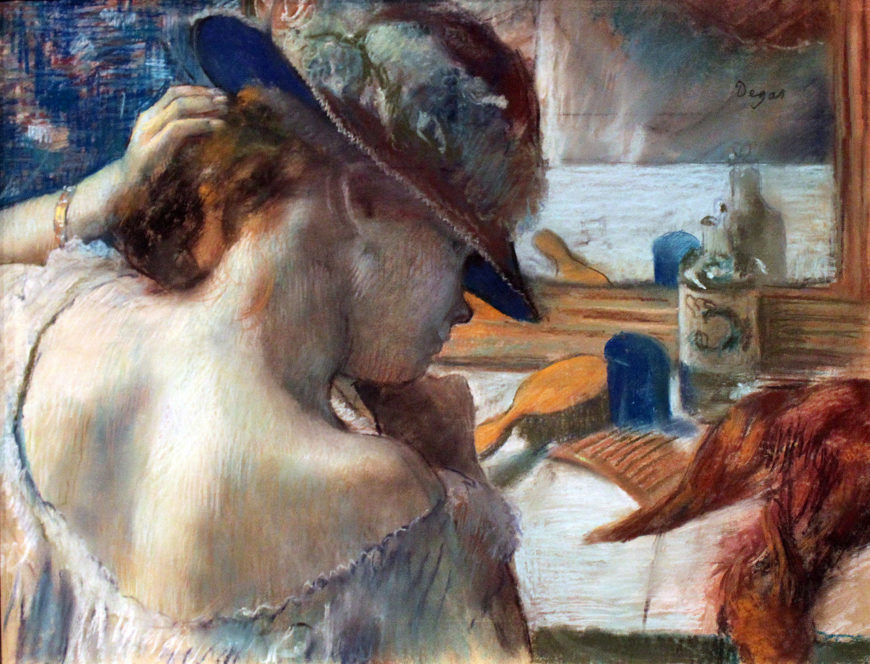

This drypoint etching, The Coiffure, of a woman adjusting her hair is one of the hundreds that Mary Cassatt made in her in-home studio in the summer and fall of 1890 and in the winter of 1891. It was inspired in part by a woodblock print in her personal collection, Kitagawa Utamaro’s boudoir image of the daughter of a prosperous Edo businessman, Takashima Ohisa Using Two Mirrors to Observe Her Coiffure. La Coiffure also has its art historical roots in Old Master paintings of women bathing and the odalisque though it departs from those conventional models to become a tightly crafted exercise in form and composition.

C. Wintz, La coiffure française illustrée, 1911, print (New York Public Library)

The word “la coiffure” evokes a precise image, one of wealthy women in glamorous settings. The ritual of grooming, dressing, and preparing one’s hair from the seventeenth and eighteenth century court days of Anne of Austria and Marie Antoinette was passed down to nineteenth-century ideals of femininity and beauty.

To wear an elaborate hairstyle such as those depicted in this magazine illustration by C. Wintz one needed to have a maid to help with one’s hair. “La coiffure” was part of a specific lifestyle. Yet the woman in Cassatt’s print is tending to her hair alone. Perhaps what we are seeing is a working woman getting ready to start her day. The counterpoint of the print’s title and the reality of its subject matter characterizes the ironic tension within the image.

Woman adjusting her bun (detail), Mary Cassatt, The Coiffure, 1890–91, color drypoint and aquatint on laid paper, 43.2 x 30.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

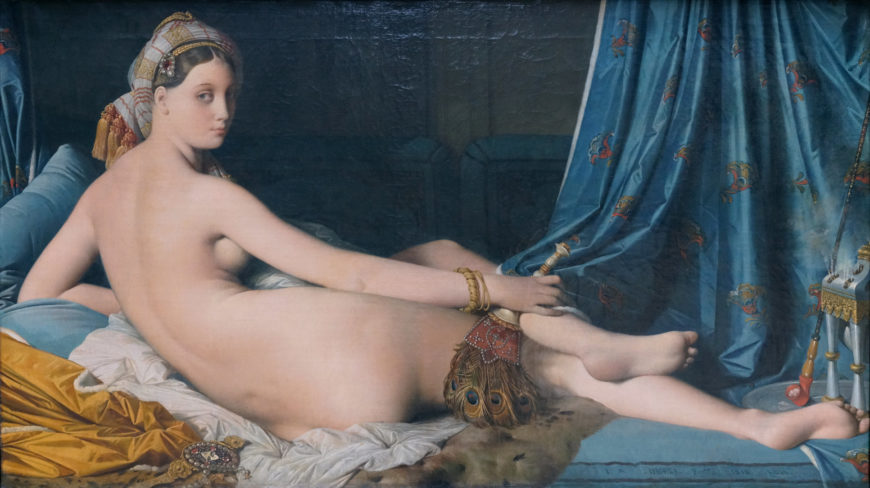

The woman in Cassatt’s La Coiffure sits in a plush armchair in front of mirror, her head focused downward, her back arched, as she adjusts her bun. The voyeuristic element to the scene is drawn from precedents in works by Rembrandt van Rijn (Bathsheba at Her Bath, 1654) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (La Grand Odalisque, 1814), which Cassatt studied at the Louvre when she was a young student in the mid 1860s.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The woman in La Coiffure, unlike Rembrandt’s Bathsheba or Ingres’ Odalisque, is not sexualized. Though her breasts are exposed, her chest and the details of her body are deliberately muted into an overall structure of curves and crisp lines. This is an exercise in clarity and tone where the subject, the woman’s body, is a compositional element in the picture—as vividly realized as the other significant patterns of the room—the wallpaper, the fabric of the armchair, and the carpet.

Woman (detail), Mary Cassatt, The Coiffure, 1890–91, color drypoint and aquatint on laid paper, 43.2 x 30.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

As the viewer, we are placed at a slight leftward angle from the woman in the chair so that we see her through her reflection in the mirror while she is looking away from it. The downward gaze is similar to that of the model in the Utamaro, is done partly in homage to the modesty of the female subject in the ukiyo-e prints (artists were always aware that their works were made for a male-dominated market and designed them to be enticing) and partly as a study of shape and line, so that the viewer, realizing that he or she is not looking at a psychological portrait, could focus more intently on the compositional elements of the work. The prints provided artists with an opportunity to showcase their skill in concision—using no more than is necessary to convey an idea—the way a haiku poet showcases similar skill within the three lines and seventeen syllables of the poem.

The curve of the woman’s sloping back and neck echoes the curves of the chair which stand in contrast to the vertical lines of the mirror—a compositional counterpoint that further enhances the tension within the tight composition. The limited color palette of shades of rose, brown, and white enables us to focus closely on the form and clarity of line. It also mimics the quality of pastels, which Cassatt, like her friend Edgar Degas, often liked to use. Through the process of the drypoint and aquatint etching, La Coiffure combines Cassatt’s propensity for hazy shading and soft tones with a bold sharpness in line allowing the artist to integrate the qualities of two disparate media.

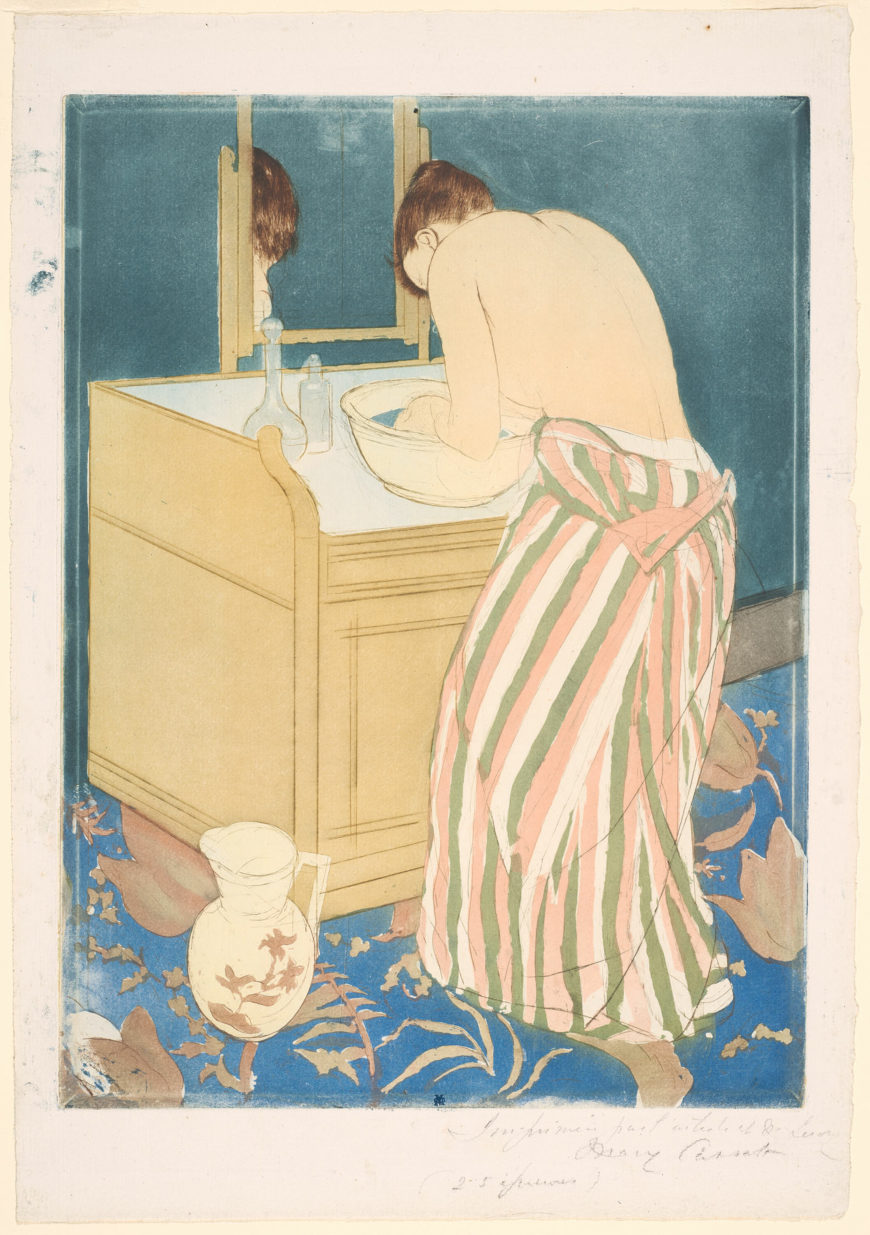

Mary Cassatt, Woman Bathing, 1890–91, color aquatint, with drypoint from three plates, on off-white laid paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

Her desire to emulate the haziness, sensual, and suggestive possibilities of pastels is what motivated Cassatt not to use woodblock printing but intaglio. First, Cassatt carved her designs onto a smooth copper plate with a fine metal needle. Then the plate would be dusted with a powdered resin and heated until the resin melted in tiny mounds that hardened as they cooled. Acid was then added on to the metal plate biting the channels along the resin droplets. The deeper penetration of acid produced richer, darker tones, while a lighter application of acid produced lighter shades of color and a variety of nuanced gradients could be generated within a single print. Once Cassatt had replicated a certain number of images from a plate, she would incise the plate with a needle so that no one could use the same image again.

The companion piece to La Coiffure is Woman Bathing, another image of a woman, bare-chested and half-dressed, grooming before a mirror.

Cassatt was inspired in part by some of Degas’ pastels of women grooming. In Cassatt’s prints, the time-honored boudoir scenes we see in Titian and Giovanni Bellini become de-eroticized and re-appropriated as skilled exercises in form, shading, and line. In the spirit of ukiyo-e and Impressionism, these prints capture fugitive, fleeting moments of the busy lives of the Parisian bourgeois and working class.

Cassatt’s motivation in making the prints was to make her art more accessible for a large audience. She believed that everyone, regardless of income or social position, should be able to experience art and to own works they enjoy:

I believe [nothing] will inspire a taste for art more than the possibility of having it in the home. I should like to feel that amateurs in America could have an example of my work, a print or an etching, for a few dollars. That is what they do in France. It is not left to the rich alone to buy art; the people—even the poor—have taste and buy according to their means, and here they can always find something they can afford.

[2]This philosophy of art for the masses wasn’t always popular with Mary Cassatt’s contemporaries, like John Singer Sargent and the art historian Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), who viewed Cassatt’s printmaking as a dilution of her precious talent. Yet Cassatt understood that as the world was changing with the twentieth century’s new industries and technology, more and more people would have the income, education, and ability to experience art in ways they hadn’t been able to before. The proliferative possibilities of the print and its evocative potential to convey so much in such a small space was just the art form to reach a wider audience.