In the decades following the French Revolution and Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo (1815) a new movement called Romanticism began to flourish in France. If you read about Romanticism in general, you will find that it was a pan-European movement that had its roots in England in the mid-eighteenth century. Initially associated with literature and music, it was in part a response to the rationality of the Enlightenment and the transformation of everyday life brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Like most forms of Romantic art, nineteenth-century French Romanticism defies easy definitions. Artists explored diverse subjects and worked in varied styles so there is no single form of French Romanticism.

Intimacy, spirituality, color, yearning for the infinite

Even when Charles Baudelaire wrote about French Romanticism in the middle of the nineteenth century, he found it difficult to concretely define. Writing in his Salon of 1846, he affirmed that “romanticism lies neither in the subjects that an artist chooses nor in his exact copying of truth, but in the way he feels…. Romanticism and modern art are one and the same thing, in other words: intimacy, spirituality, color, yearning for the infinite, expressed by all the means the arts possess.”

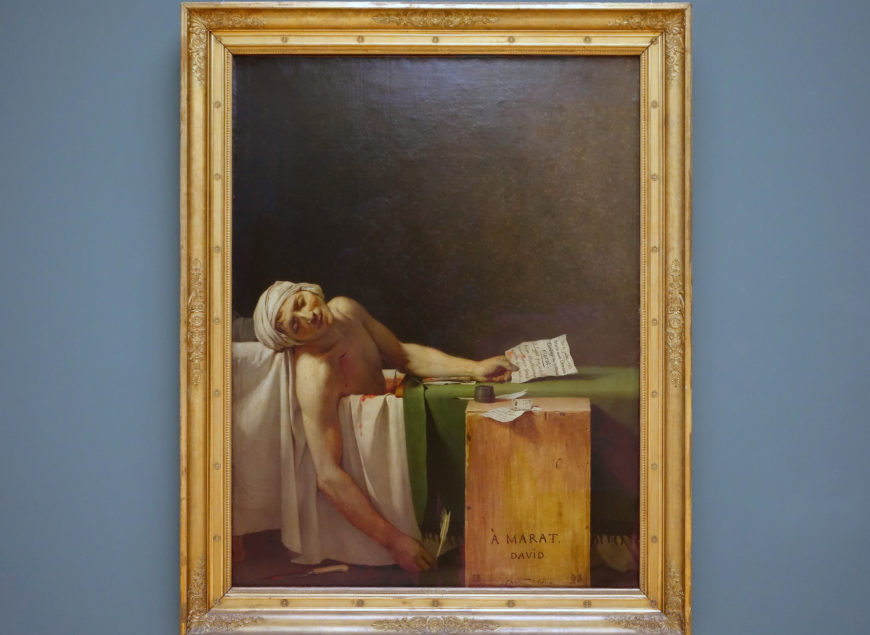

Jacques-Louis David, Death of Marat, 1793, oil on canvas, 165 x 128 cm (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One might trace the emergence of this new Romantic art to the painting of Jacques-Louis David who expressed passion and a very personal connection to his subject in Neoclassical paintings like Oath of the Horatii and Death of Marat. If David’s work reveals the Romantic impulse in French art early on, French Romanticism was more thoroughly developed later in the work of painters and sculptors such as Theodore Gericault, Eugène Delacroix and François Rude.

In 1810, Germaine de Staël introduced the new Romantic movement to France when she published Germany (De l’Allemagne). Her book explored the concept that while Italian art might draw from its roots in the rational, orderly Classical (ancient Greek and Roman) heritage of the Mediterranean, the northern European countries were quite different. She held that her native culture of Germany—and perhaps France—was not Classical but Gothic and therefore privileged emotion, spirituality, and naturalness over Classical reason. Another French writer Stendhal (Henri Beyle) had a different take on Romanticism. Like Baudelaire later in the century, Stendhal equated Romanticism with modernity. In 1817 he published his History of Painting in Italy and called for a modern art that would reflect the “turbulent passions” of the new century. The book influenced many younger artists in France and was so well-known that the conservative critic Étienne Jean Delécluze mockingly called it “the Koran of the so-called Romantic artists.”

The direct expression of the artist’s persona

The first marker of a French Romantic painting may be the facture, meaning the way the paint is handled or laid on to the canvas. Viewed as a means of making the presence of the artist’s thoughts and emotions apparent, French Romantic paintings are often characterized by loose, flowing brushstrokes and brilliant colors in a manner that was often equated with the painterly style of the Baroque artist Rubens. In sculpture artists often used exaggerated, almost operatic, poses and groupings that implied great emotion. This approach to art, interpreted as a direct expression of the artist’s persona—or “genius”—reflected the French Romantic emphasis on unregulated passions. The artists employed a widely varied group of subjects including the natural world, the irrational realm of instinct and emotion, the exotic world of the “Orient” and contemporary politics.

Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, oil on canvas, 193 x 282″, 1818–19 (Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Man and nature

The theme of man and nature found its way into Romantic art across Europe. While often interpreted as a political painting, Théodore Géricault’s remarkable Raft of the Medusa (1819) confronted its audience with a scene of struggle against the sea. In the ultimate shipwreck scene, the veneer of civilization is stripped away as the victims fight to survive on the open sea. Some artists, including Gericault and Delacroix, depicted nature directly in their images of animals. For example, the animalier (animal sculptor) Antoine-Louis Barye brought the tension and drama of “nature red in tooth and claw” to the exhibition floor in Lion and Serpent (1835.)

Antoine Louis Barye, Lion and Serpent, cast in 1835, 135 x 178 x 96 cm (Louvre, Paris) (photo: Yann Caradec, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Not solely reason, but also emotion and instinct

Théodore Géricault, Portrait of a Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy, also known as The Hyena of the Salpêtrière, c. 1819–20, 72 x 58 cm (Musee des Beaux-Arts de Lyon)

Another interest of Romantic artists and writers in many parts of Europe was the concept that people, like animals, were not solely rational beings but were governed by instinct and emotion. Gericault explored the condition of those with mental illness in his carefully observed portraits of the insane such as Portait of a Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy (The Hyena), 1822. On other occasions artists would employ literature that explored extreme emotions and violence as the basis for their paintings, as Delacroix did in Death of Sardanapalus (1827–28.)

Eugène Delacroix, who once wrote in his diary “I dislike reasonable painting,” took up the English Romantic poet Lord Byron’s play Sardanapalus as the basis for his epic work Death of Sardanapalus (below) depicting an Assyrian ruler presiding over the murder of his concubines and destruction of his palace. Delacroix’s swirling composition reflected the Romantic artists’ fascination with the “Orient,” meaning North Africa and the Near East—a very exotic, foreign, Islamic world ruled by untamed desires. Curiously, Delacroix preferred to be called a Classicist and rejected the title of Romantic artist.

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, oil on canvas, 12′ 10″ x 16′ 3″ / 3.92 x 4.96m (Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Whatever he thought of being called a Romantic artist, Delacroix brought his intense fervor to political subjects as well. Responding to the overthrow of the Bourbon rulers in 1830, Delacroix produced Liberty Leading the People (below, 1830). Brilliant colors and deep shadows punctuate the canvas as the powerful allegorical figure of Liberty surges forward over the hopeful and despairing figures at the barricade.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (July 28, 1830), September–December 1830, oil on canvas, 260 x 325 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

François Rude, La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792), 1833–6, limestone, c. 12.8 m high, Arc de Triomphe de l’Etoile, Paris (photo: Storm Crypt, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

That intensity of emotion, so characteristic of French Romantic art, would be echoed if not amplified by the sculptor François Rude’s Departure of the Volunteers of 1792 (La Marseillaise) (1833–6). Its energetic winged figure of France/Liberty, a modern Nike, seems to scream out as she leads the native French forward to victory in one of the very few Romantic public monuments.

Today, French Romanticism remains difficult to define because it is so diverse. Baudelaire’s comments from the Salon of 1846 may still apply: “romanticism lies neither in the subjects that an artist chooses nor in his exact copying of truth, but in the way he feels.”

Additional resources:

Romanticism on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Legacy of Jacques Louis David

Romantic Circles (University of Maryland)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”RomanticFrance,”]