A Day at the Races

The Derby Day by William Powell Frith captures the excitement of one of the premier events in British horse racing, The Derby (pronounced “dar-bee”) held annually at Epsom Downs in Surrey. His large-scale canvas illustrates the event during the Victorian era, capturing the milling crowd, festive atmosphere, and general excitement of the day. The horse race in the background takes a decided back seat to the many personalities in the congested throng of people in the foreground. The crowd, which presents a cross-section of Victorian society, is what captures the attention of the viewer.

Thimble rigger (detail), William Powell Frith, The Derby Day, 1856–58, oil on canvas, 101.6 × 223.5 cm (Tate Britain)

The large painting contains representatives from all social classes. On the left side, a well-dressed group of men make bets on the sleight-of-hand tricks of a thimble rigger at a makeshift table. Nearby a ruddy-faced young man in a country drover’s smock has his hand in his pocket, while an anxious woman tries to stop him from making an unwise bet on the swindler’s game. To the other side of the trickster’s table, a young man stands checking his empty pockets, the victim of a pickpocket.

Right side (detail), William Powell Frith, The Derby Day, detail of the scene around the thimble rigger, 1856–58, oil on canvas, 101.6 × 223.5 cm (Tate Britain)

On the far right, an unhappy-looking young woman seated in a carriage tries her best to ignore both the advances of a fortune-teller and her equally bored male companion, who leans against the vehicle assessing a barefoot girl selling flowers with a predatory gaze.

Center (detail), William Powell Frith, The Derby Day, 1856–58, oil on canvas, 101.6 × 223.5 cm (Tate Britain)

In the center of the painting, children sprawl on the ground. The top-hatted men mix not only with well-dressed women, but also with a woman holding a baby begging coins from the more affluent people in the carriages. The viewer’s eye is attracted to a pair of tumblers dressed in white. While the older of the two holds out his arms to “catch” the other, the child’s attention is distracted by the picnic being spread in front of the carriages by a footman. It is a stark reminder of the differences in diet between rich and poor during the period. It is also an indication of the Victorian preoccupation with the issue of class mixing, a reality of modern life, but one of which many Victorians were wary.

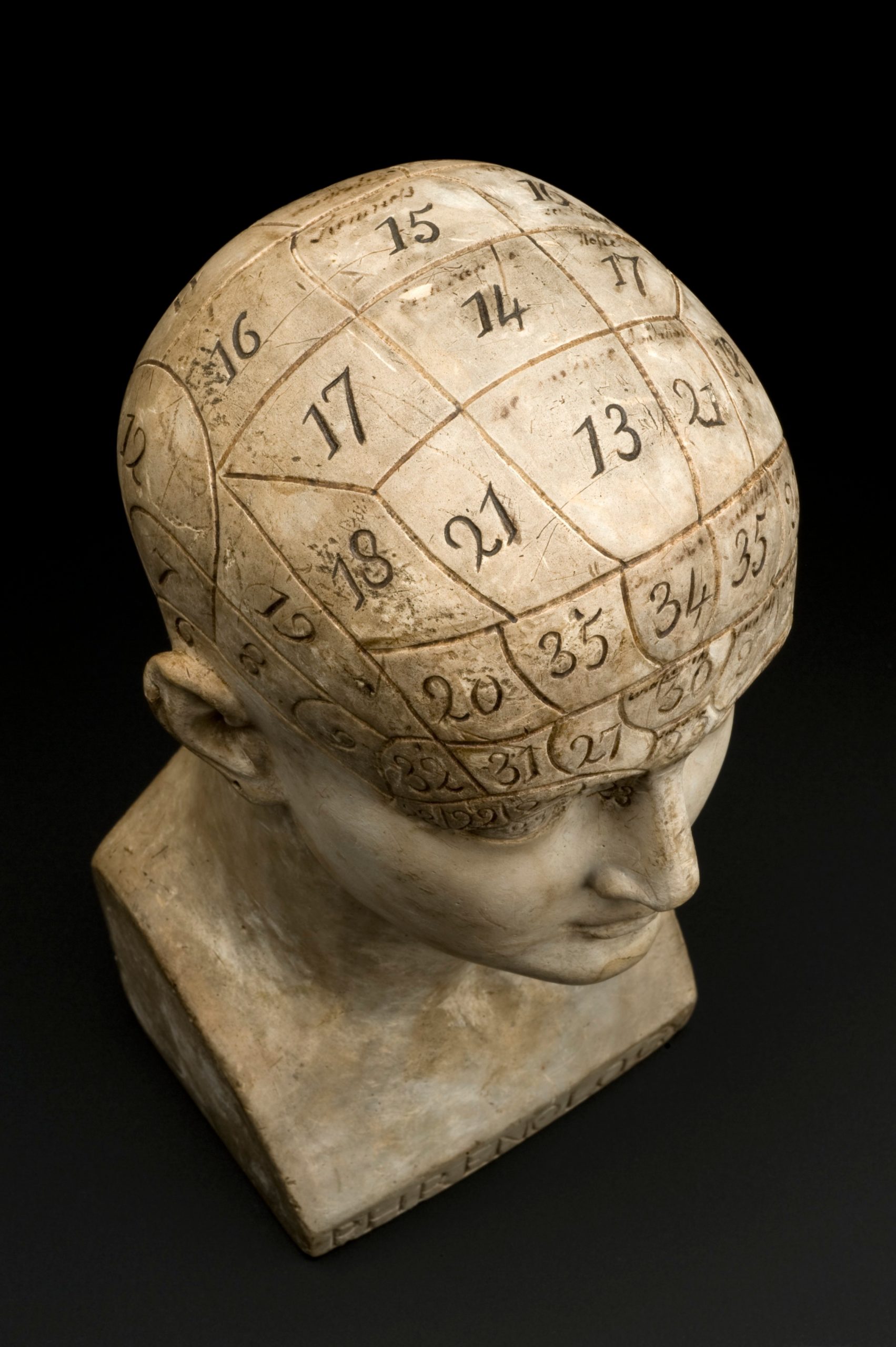

Earthenware phrenological bust, areas are marked off with an impressed line, by J. De Ville, London, 1821 (Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0)

The Social Spectrum

Another element employed by Frith to create identifiable “types” was the Victorian interest in phrenology, or the study of the shape of the skull. Developed in the late 18th century, phrenologists took detailed measurements of the head and looked for variations such as bumps or indentations to determine particular character traits. Although largely discredited as a “science” as early as the 1840s, phrenology was a popular topic in Victorian lecture halls, and even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert invited a phrenologist to “read” the heads of their children.

Another popular idea was that of physiognomy or the idea that one’s character or personal characteristics can be seen in the body, particularly in the face. Scholars have pointed out that Frith used these ideas in his paintings to distinguish between, for example, a decent working man and a shopworker mimicking the middle class he aspires to join. For Frith, this was another way, besides dress, to categorize the individuals in his modern life ensemble. And for the Victorian audience, these pseudo-sciences were a quick, although completely inaccurate, way to classify the wide variety of people they came into contact with in the new industrial society.

William Powell Frith, Ramsgate Sands (Life at the Seaside), 1851–54 , oil on canvas, 77.0 x 155.1 cm (Royal Collection Trust)

It was this attention to the social spectrum that enthralled Victorian viewers. Frith began his career painting literary scenes and portraits, but he is best known as a commentator on modern life. The first of his great modern life subjects, Life at the Seaside: Ramsgate Sands, was painted in 1854 after a family holiday to the seaside. The picture was immediately purchased by Queen Victoria. Another of his well-known paintings, The Railway Station of 1862, depicts the interior of Paddington Station. Again, Frith captured modern Victorian life, not only in the mixing of social classes, but in the still fairly new mode of transportation (the first railway opened in Britain in 1825) and the state-of-the-art train station designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Such pictures showed the Victorians as they liked to see themselves, as a prosperous, progressive, and technologically advanced society.

William Powell Frith, The Railway Station, c.1862–1909, oil on canvas, 54.1 x 114.0 cm (Royal Collection Trust)

When Derby Day was displayed at the Royal Academy, so many people flocked to see it that a police constable was stationed by the canvas to keep it from being damaged by the jostling crowds. The Art Journal in October 1858 described the painting as “a popular subject with a large section of the English people, having its upper extremity in the drawing-rooms of Belgravia, and its lower in the darkest nooks of Whitechapel; and within these lie diversely-charactered and many-shaded varieties of society.” (p. 296) Everyone wanted to have a look at the cast of characters Frith created. Today their variety is equally compelling and provides the modern viewer with a fascinating glimpse into Victorian life.

Additional resources

From Charles Dickens to Scenes of Victorian Life: The Works of William Powell Frith on ArtUK

William Powell Frith at Tate Britain

Mary Cowling, The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Pamela Fletcher, “Happiness Lost: William Powell Frith and the Painting of Modern Life,” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, vol. 33, no. 2, (2011) , pp. 147-160.

Phrenology on the Victorian Web

Mark Bills and Vivien, eds, William Powell Frith: Painting in the Victorian Age (Yale University Press, 2007).