William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott, c. 1888–1905, oil on canvas, 74 1/8 X 57 5/8 inches (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

A Lady Cursed

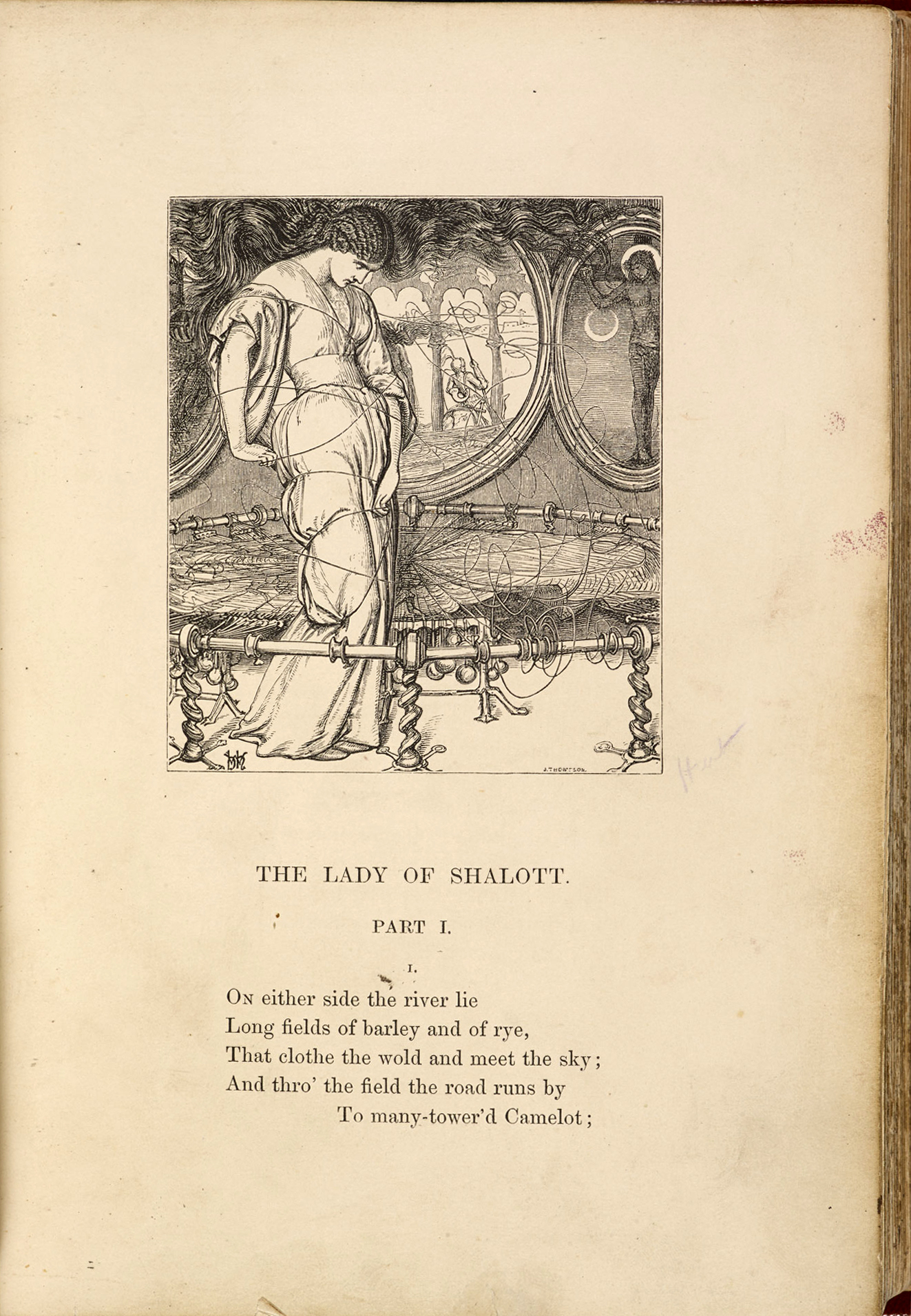

In the 1880s, William Holman Hunt turned to the poetry of Sir Alfred, Lord Tennyson, a favorite Victorian literary source, in his painting The Lady of Shalott. Hunt’s painting is a virtuoso performance, using the meticulous detail of Pre-Raphaelitism to capture the most dramatic moment in the story. The painting was based on a drawing for a lavish edition of Tennyson published in 1857 known as the Moxon Tennyson (after the publisher).

William Holman Hunt’s illustration of The Lady of Shallot, Moxon edition of Tennyson’s Poems, 1857 (The British Library)

The Victorians loved nothing better than a beautiful, tragic heroine, preferably one in medieval clothing, which explains their enduring fascination with Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott. One of his many poems based on the legends of King Arthur, Tennyson tells the story of a lovely lady confined to “Four gray walls, and four gray towers,” and cursed to constantly weave scenes that she can only observe through a mirror. As the poem explains:

No time hath she to sport and play:

A charmed web she weaves alway.

A curse is on her, if she stay

Her weaving either night or day,

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be;

Therefore she weaveth steadily,

Therefore no other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

Unfortunately for the lady, her routine of constantly weaving reflections is quite literally shattered when she observes Sir Lancelot riding by and actually looks out the window rather than at the shadowy images in the mirror.

She left the web, she left the loom

She made three paces thro’ the room

She saw the water-flower bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look’d down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Knowing that the end is near, the final part of the poem recounts how the lady writes a message for those that will find her body, gets into a boat, and floats down the river to Camelot. In this, Tennyson’s poem ends as did many, many other stories popularized during the era, with the untimely demise of the lovely heroine.

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888, oil on canvas, 153 × 200 cm (Tate Britain)

The subject was frequently illustrated, the most familiar example being John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott, which depicts a beautiful but stricken looking lady dying as she slowly floats down the river. In selecting this of the part of the story, Waterhouse was not alone, as the vast majority of renditions of this subject focused on the trip down river, with the lady either already dead or about to die.

In contrast, Hunt illustrated the most active part of the poem, when the lady actually looks out the window, causing the mirror to crack. According to the text, “she made three paces thro’ the room,” and in Hunt’s figure, the swinging arms and the wild, wind-blown look of her flowing hair create the sensation of a slow rhythmic dance. The lady struggles to remove threads of her tapestry, which “out flew the web and floated wide,” creating long colored strings that bind the figure. Much of this can also be seen in the original drawing and were elements not appreciated by Tennyson himself who complained that her hair was like a “tornado” and that the threads encircling her body were an addition to the actual text of the poem.

Mirror (detai;), William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott, c. 1888–1905, oil on canvas, 74 1/8 X 57 5/8 inches (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

Hercules, shoes and irises (detail), William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott, c. 1888–1905, oil on canvas, 74 1/8 X 57 5/8 inches (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

Symbols and Meanings

In the painting, Hunt added many symbolic references. The cracked mirror behind the lady’s head shows Lancelot on his way to Camelot and the river that will take her on her final journey. The subject of the tapestry she weaves, Sir Galahad delivering the Holy Grail to King Arthur, provides a virtuous counterpoint to Lancelot, whose adultery with Queen Guinevere ultimately brings down Camelot. To one side of the mirror, a decorative panel depicting Hercules trying to pluck a golden fruit in the Garden of Hesperides is reminiscent of Renaissance relief sculpture, something Hunt saw much of during an earlier stay in Florence. The same can be said for the decorative tile floor, which is similar to that used by Hunt in his earlier painting Isabella or the Pot of Basil begun during his stay in Florence.

Hunt was a religious man, and included elements that may be interpreted as Christian symbolism—a pair of empty shoes and two purple irises. In the Bible shoes are often removed before walking on sacred ground. For example, a similar device is used in the famous Northern Renaissance painting by Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, which was a favorite of the Pre-Raphaelites. The delicately painted irises are associated with faith, hope, and wisdom, and for a Victorian audience intimately aware of the language of flowers, this inclusion may have had special meaning for the tragic lady who was “half sick of shadows,” and in the throes of making a life-changing decision.

Feminist scholars have noted that the story can be seen as a cautionary tale of what happens to women who flout the rules; in this case it is the lady’s obvious sexual desire for Lancelot that drives her decision to actually look out the window and bring the curse upon herself. And although a moralistic meaning would certainly have appealed to Hunt, his depiction of the lady is not unsympathetic. The reflection of the bright sunshine in the mirror is in sharp contrast to the darkness around the lady’s face and upper torso, while her lower half is bathed in light. His lack of overt condemnation of her actions is reminiscent of his more charitable approach towards what Victorians saw as the sin of prostitution in his earlier painting The Awakening Conscience. Although as a reader one must wonder how she ended up cursed in a tower in the first place, we are forced to admire her decision to free herself from her prison.

William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott, c. 1888–1905, oil on canvas, 74 1/8 X 57 5/8 inches (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

The Lady of Shalott is a powerful example of later Pre-Raphaelitism. At a time when many artists were moving towards the ideas of Aestheticism where beauty is more important than subject, Hunt’s picture exhibits his meticulous attention to detail combined with his desire to include a narrative. His focus on the climatic action of the story, rather than the passivity of the lady’s death, grips his viewer with the moment of decision that will change the course of her life. Although Victorian painting abounds with images of women who, by the end of the story, will end up dead, Hunt’s portrayal of his subject shows a woman unwilling to accept the drudgery of her life and ready to make a change, no matter what the cost.

Additional resources