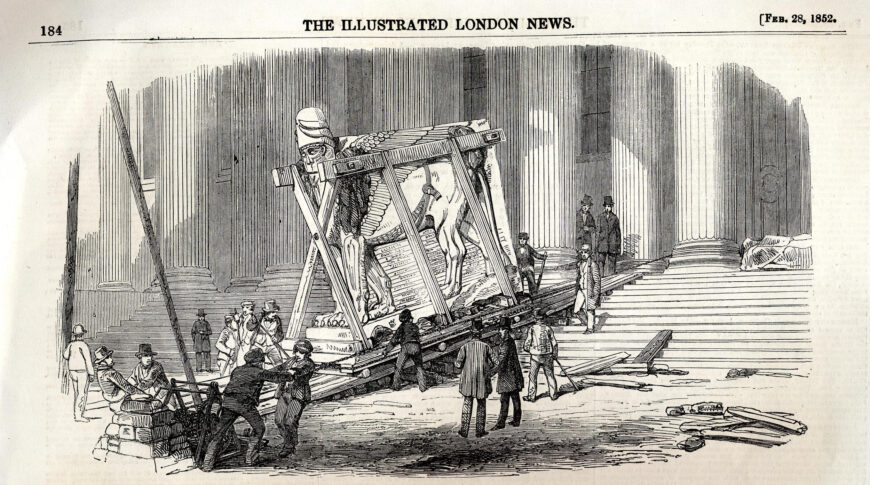

“Reception of Nineveh Sculptures at the British Museum,” Illustrated London News (February 28, 1852) (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London), p. 184

A winged lion with a human head is carted into the grand portico of the British Museum, something never seen before in London: the arrival of a lamassu, an ancient Assyrian guardian figure more than two thousand years old. Clearly this was a newsworthy event in 1852—for those who could not be there to watch, the News provided an engraving of the arrival of these majestic creatures entering the museum.

Sir Austen Henry Layard (an archaeologist) and his protégé Hormuzd Rassam, a Christian Iraqi, discovered this lamassu and other remarkable large-scale sculptures in Iraq and transported them to the British Museum. [1] The sculptures sparked a wave of interest in ancient Assyria and in the region traditionally called the ancient Near East. In Victorian Great Britain, Assyrianizing art, jewelry, and architecture were produced in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. They reflected a growing interest in archaeology and in ancient Western Asia, as well as the British Empire and capitalism. The study of the art and architecture that adapts and reinterprets ancient art and architecture is typically called reception studies.

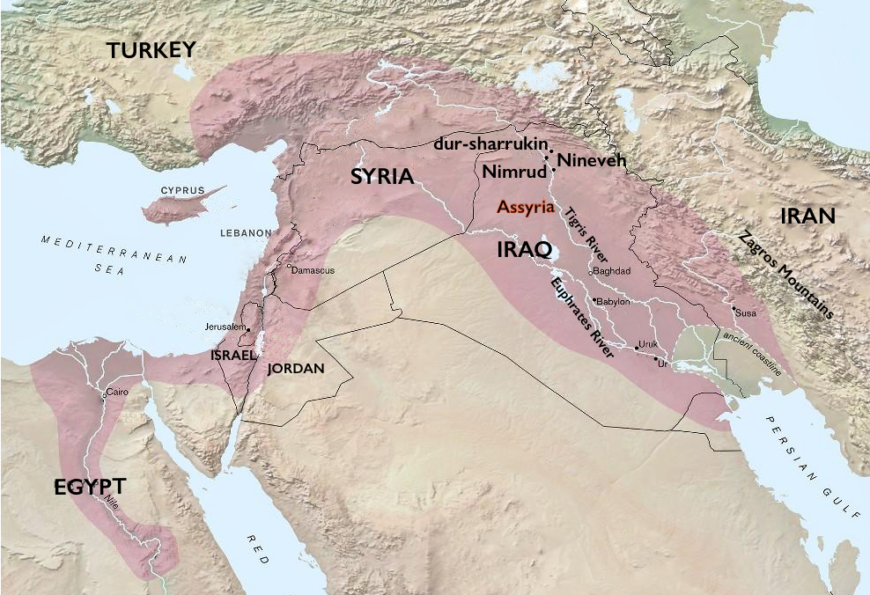

Map of the Assyrian empire at its greatest extent during the reign of Ashurbanipal (668 B.C.E. to c. 627 B.C.E.)

Working under the auspices of the British Consul at Constantinople, Layard made major discoveries at Nineveh and Nimrud in modern-day Iraq between 1845 and 1851. Layard was largely a self-made and self-educated man. He was not the first to excavate major sites from the ancient Assyrian Empire. While far from perfect, from the perspective of modern archaeology, Layard’s excavations were more systematic than many of his peers. A talented draftsman, he drew plans and made illustrations of the reliefs and statues he unearthed. He also imagined what these spaces could have looked like through colorful reconstructions. An excellent writer and self-promoter, Layard published several books about his discoveries, including the large-scale, beautifully illustrated Monuments of Nineveh (1849) and Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon (1853). His findings were made accessible to the larger public through the affordable and abridged Layard’s Nineveh (1851). This book and the newspaper reports fueled popular interest in ancient Assyria and Mesopotamia.

The “Nineveh” Court at the Crystal Palace at Sydenham

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations was held in London in 1851 and is considered the first World’s Fair. Known as the Crystal Palace, it was re-erected in 1854 in the London suburb of Sydenham. This second Crystal Palace contained ten Fine Arts Courts. Of these courts, which included Egyptian, Pompeian, Greek, and Roman sculptural courts, the largest was the Assyrian or “Nineveh” Court. Samuel Laing, who chaired the company that opened the Crystal Palace, called it an “illustrated encyclopedia,” one that was aimed at all levels of British society, including the working classes.

The inclusion of casts of Assyrian art at the Nineveh Court was grounded in the concerns of Victorian Great Britain and was fueled by three men: James Fergusson, Owen Jones, and Layard. James Fergusson was a noted architect and architectural historian who designed the court. Owen Jones was one of the most important architecture and design theorists of 19th-century Britain and a driving force behind the creation of the Fine Arts Courts at the Crystal Palace. Layard served as an advisor and authored the court’s eighty-page guide.

Francis Bedford, “Exterior of the Assyrian Palace” from Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham (London: Day and Son, 1854) (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven)

The court was an immersive space; almost like virtual reality before such a thing existed. The Nineveh court was in fact a combination of Mesopotamian and Persian architectural elements, fusing Layard’s discoveries at Nineveh and Nimrud with discoveries from Susa, Persepolis, and Khorsabad. The casts used in the court were taken from sculptures and bas-reliefs in the Louvre and British Museum.

The goal of the Assyrian Court and the other courts was to educate the public. Fergusson firmly believed that Assyria and its architecture should be part of the public’s understanding of the past. For Fergusson and Layard, Assyria was artistically important and should be viewed as a point in history that Victorian progress could be compared against. By calling it the Nineveh Court, the organizers were connecting the art on exhibit to the Bible. Perhaps the most well-known mention of Nineveh is from the Book of Jonah, whose mission was to preach to the city and to encourage its inhabitants to repent (Jonah 3:1–10). By framing it as the Nineveh court, Fergusson and Layard put ancient Assyrian art, architecture, and culture into a framework that the British public would understand.

While the casts in the court were smaller versions of the original reliefs and sculptures, Layard’s guide proclaimed the archaeological accuracy of the individual elements, stating that the court’s design came from “Mr. Fergusson, who has especially devoted himself to the study of Assyrian architecture, and has spared no pains to examine and compare every fragment of architectural ornament and detail, as well as every monument, which might throw light upon the subject, discovered during the researches of M. Botta and the Author in Assyria.”

The court’s reliefs and lamassus were painted. The reliefs and statues that arrived at the British Museum had been painted but their color had faded. The application of color to the casts was another example of an attempt at archaeological accuracy. The inclusion of color also reflected the aims of Owen Jones. His Grammar of Ornament (1856), one of the most important 19th-century design sourcebooks, emphasized color and historical designs and sought to interject them into Victorian design and aesthetics. Improving British design was a major concern of the mid-19th century, as leading members of the British artistic and design community were concerned that Britain was falling behind other European powers. In response to this fear, the Government School of Design was established in 1837, the first-ever design school in Britain. The 1851 and 1854 Crystal Palaces both sought to showcase British design and products. The Victoria and Albert Museum was founded originally as the Museum of Manufactures in 1852, as a direct consequence of the World’s Fair and this desire.

The design, art, architecture, and color of the Assyrian Court were grounded in the concerns of the day: it sought to educate the public about ancient Assyria as well as provide models for contemporary architecture and design principles. Some of the Crystal Palace’s more “refined” or sophisticated critics, such as Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, did not appreciate the use of color. The Spectator magazine did not approve of the use of red, blue, and yellow with white. The fact that ancient sculptures were brightly painted is still a major point of contention today; certain scholars and members of the public remain unwilling to accept that archaeology, material science, and scholarship have demonstrated that the ancient world was full of vibrant color.

During the first year of operation, the Crystal Palace had 1,332,000 visitors while the British Museum, where many of the original Assyrian statues were displayed, only had 395,564 visitors. While the display of “Assyrian” Court and the other ancient courts were quasi-accurate at best, they did more to educate—and entertain—a wider section of the British population, making the discoveries and ancient cultures more accessible to those who could not visit the British Museum or felt that they were not welcome there. The court brought ancient Assyria and ancient Western Asia home to the British public. While it was never explicitly stated, such a court also legitimized the British involvement in the archaeology and politics of Western Asia. Layard and Fergusson became the interpreters of ancient civilizations, and the court popularized and democratized archaeology and the study of the past, but it also claimed interpretation and ownership of these sites for the British, who had assumed the position of being a global power. [2] Thus, these reinterpretations can be seen through the lens of Orientalism, the idea that European nations sought to control regions in the “East” (i.e. the Middle East or West Asia and North Africa) through archaeology, travel, imperialism, industrialization, mass production, and colonization.

Parian wares: lamassus for the middle classes

As the ranks of the British middle class swelled, so too did their purchasing power, and objects in the style of Assyrian sculptures became popular to display in one’s home. They spoke to one’s learnedness, sophistication, and cultural standing. But how to make these on a mass scale? In 1844, the English pottery firm Copeland & Garrett developed Parian ware, a type of porcelain that takes its name from Parian marble but because it could be cast or molded, it was perfect for the mass production of small-scale figures for the middle classes.

Aaron Hays, Parian Book-ends in the form of a winged, human-headed bull, Parian porcelain, 22 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Aaron Hays, who worked at the British Museum as an attendant, was an amateur sculptor. Working with Alfred Javis, another British Museum attendant, he created small statues that were modeled on the colossal guardian figures from Nimrud and Sargon’s Palace at Khorsabad. They became used as bookends. He also sold lion paper weights and a relief plaque of Ashurbanipal and his queen in a garden scene. The figures were adapted to suit Victorian aesthetics and were more life-like and less formalized than the actual sculptures. [3] In addition to the book ends, other figures including Sennacherib, Sardanapalus, and his queen, as well as a vase, were sold as souvenirs at the British Museum. These figures are the precursors to the book ends that one can still purchase today from the British Museum or the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jewelry

Another manifestation of the craze for Assyrian art was found in the production of high-end Assyrian-style jewelry for aristocratic ladies and newly-minted British millionaires. This type of jewelry was being produced as early as the 1850s. Examples were on display at the Great Exhibition of 1851, but most surviving examples come from the 1860s and 1870s.

Assyrian-style Bracelet, 1872, gold and enamel, 3 x 6 cm, produced by Backes & Strauss Ltd (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The firm of Backes & Strauss Ltd produced a gold bracelet with applied and enameled relief in navy blue, brown, gold, red, and light green. We see Assyrian archers and charioteers hunting lions, while a palm tree provides shade and two ominous vultures circle looking for carrion. A thin band of engraved foliage frames this scene. This design was based on the hunting reliefs in the British Museum, but was originally from Ashurbanipal’s 7th century B.C.E. palace in Nineveh. These bracelets were designed in what scholars call the “archaeological style.” They were meant to be archaeologically informed (but not entirely accurate)—like the architecture and reliefs of the Assyrian Court at the Crystal Palace. The designers likely worked from quasi-accurate line drawings that were circulating in popular publications rather than the reliefs themselves. The designs embellished the ancient models to make them suitable to Victorian tastes. In this case, the vultures and palm tree are 19th-century additions. While the figures were Assyrian, their organization and the composition of the scene were also very Victorian. Other bracelets showed kings with killed lions, while brooches and golden studs featured winged guardian figures, or even integrated ancient cylinder seals. The most famous example of Assyrian-style jewelry was a set of a necklace, earrings, and bracelet that Layard commissioned for his wife, Enid, for their marriage, from Phillips Brothers & Sons. They were composed of ancient cylinder seals from his excavations mounted in a modern gold setting.

Lady Layard’s Necklace, 1900–1800 B.C.E. with gold setting dating to the 1850s C.E., gold, stone, excavated and commissioned by Sir Austen Henry Layard (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

While the taste for Assyrianizing art, architecture, and jewelry did not last much beyond 1880, its popularity for three decades in the middle of the 19th century demonstrates the importance of archaeological discoveries in shaping later aesthetics. The debates over the use of color at the Nineveh Court at the Crystal Palace also reflect that the interpretation of ancient art and architecture is often shaped and influenced by present debates and considerations.

Notes:

[1] Layard had permission from the Ottoman Empire to export his finds.

[2] Assyria made other appearances at World’s Fairs. At the famous Paris Exposition of 1889, for which the Eiffel Tower was constructed, the architect Charles Garnier included an Assyrian house in his “Histoire de l’habitation humaine” exhibition. This exhibit included examples of historical houses from civilizations that he believed had contributed to the history of architecture. While no more architectural reproductions were created for World’s Fairs, objects from ancient Western Asia and the “Holy Land” (lands mentioned in the Bible) were displayed at American and European World’s Fairs.

[3] Although the Parian porcelain was intended to evoke marble, the original statues were carved from gypsum, leading some scholars to argue that the faux Parian material was a way to make these works appear more classical, and thus more favorable. Greek Art was viewed as the apex of artistic production by many at this time.

Additional resources

Overview of Assyria on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Charlotte Gere and Judy Rudoe, Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World (London: British Museum, 2010).

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains (London: John Murray, 1849).

Austen Henry Layard, The Nineveh Court in the Crystal Palace (London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans, 1854).

Kevin McGeough, “Progress, Design, and Hyperreal Spectacle: The Ancient Near East in Nineteenth-Century Expos, Fairs, and Geographical Amusements,” Near Eastern Archaeology, volume 85, number 1 (2022), pp. 54–65.

Kevin McGeough, “Assyrian Style and Victorian Materiality: Mesopotamia in British Souvenirs, Political Caricatures, and the Sydenham Crystal Palace,” Art/ifacts and Artworks in the Ancient World, edited by Karen Sonik (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), pp. 415–46.

Judy Rudoe, “Assyrian-style Jewellery,” Antique Collector (April, 1989), pp. 42–48.

Erhan Tamur, “From ‘Near East’ to ‘Western Asia’: A Brief History of Archaeology and Colonialism,” The Morgan Library & Museum (blog).