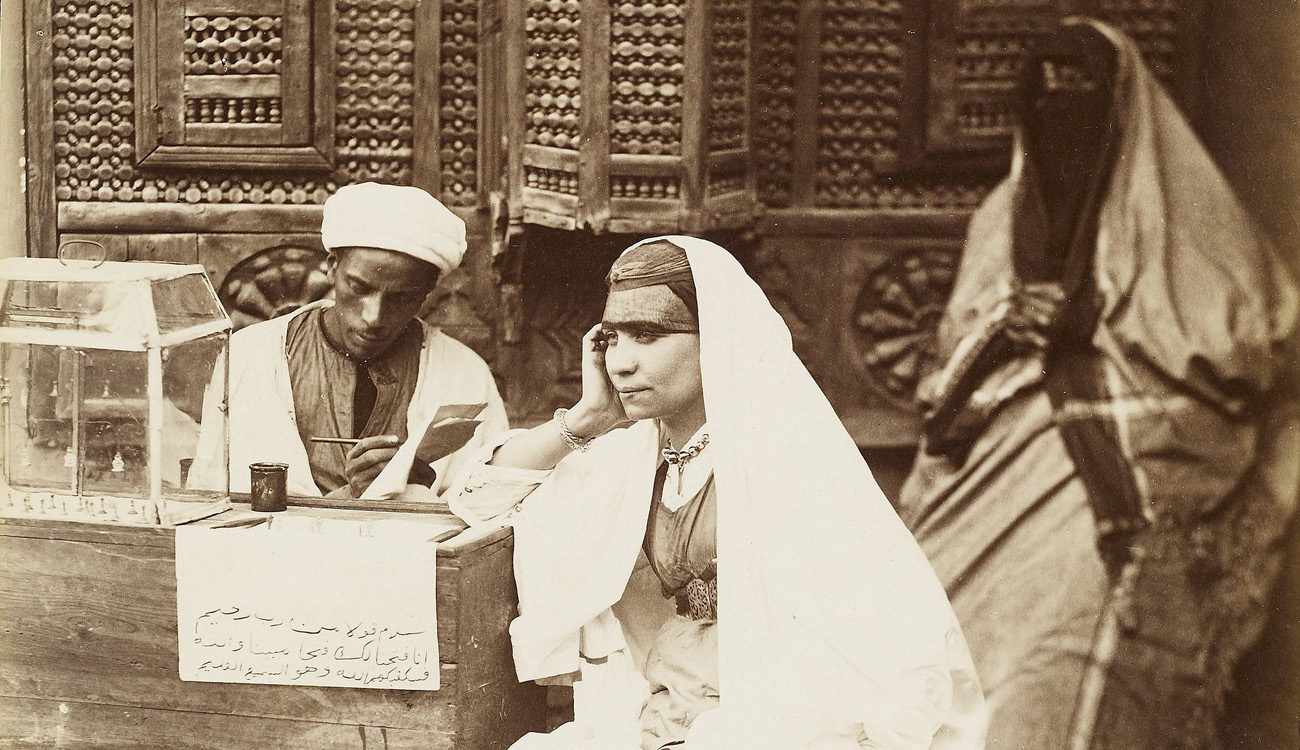

Ecrivain public (public scribe), detail, about 1872, Otto Schoefft. Unmounted albumen print, 24.7 x 19.5 cm. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.R.3. Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photography Collection

I first became interested in Orientalist, mainly Egyptian, photographs of the nineteenth century when I saw several original prints in the collection of Bernd Stiegler, a colleague and friend at the University of Konstanz. Intrigued, I began to study exhibition catalogues and illustrated books on the subject. The same names came up again and again as the makers of these vintage prints: the Greek Brothers Zangaki, the Frenchmen Félix Bonfils and Emile Bechard, the Italians Antonio Beato and Luigi Fiorillo, the Turk of Kurdish ancestry Pascal Sébah and—less frequently—a certain Otto Schoefft.

Wondering if more of these pictures existed, I googled these names—and an avalanche of images appeared. Try it yourself. Here you can discover a rich, appealing distant world: the world of the pharaonic monuments alongside the Nile, sometimes the Nile itself with its crocodile-hunters and their (mostly stuffed) victims, and also the world of the Egyptian working people of 150 years ago. For me, these images were more than interesting; their gold-enhanced sepia tone gave them a special allure.

Clicking on one of the thumbnails in my Google searches typically led either to the page of an anonymous eBay seller, or—much better—to a museum collection with an important fund of Orientalist photographs. I regularly landed at the Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photograph Collection housed at the Getty Research Institute, a particularly rich and well-balanced anthology assembled by one of the leading specialists in the field, Ken Jacobson. Each item in this important collection is now accessible through the Research Institute’s Primo Search. The website allows free download of the images at excellent quality, and every item is furnished with reliable information. (One should not forget: behind a seriously digitized collection of photographs there is the enormous time-consuming work of cataloguing—which includes measuring, describing, dating, and attributing—done by scholars specialized in the field.)

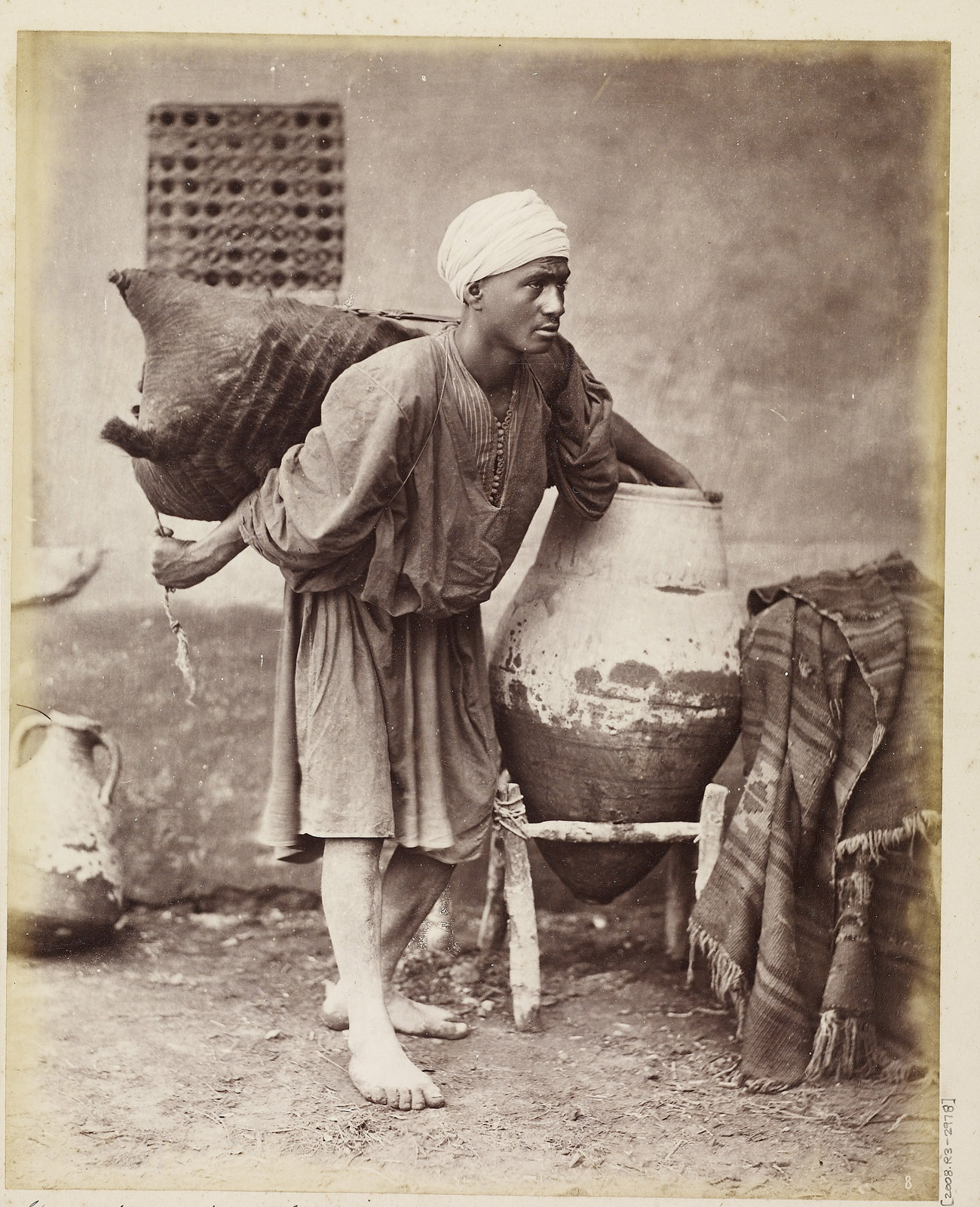

The images that interested me most were early photographs, produced between about 1865 and 1880, showing the multiracial population of Cairo in their everyday occupations. The Sakkah, for example, carried, barefoot, a heavy burden of Nile water in a goat skin to households, where it was filtered in a large vessel before use.

Sakkah (water carrier), Egypt, about 1872, Otto Schoefft. Albumen print mounted on period card, 24.7 x 19.5 cm. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.R.3. Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photography Collection

The earliest prints showed people in staged studio situations, but from about 1870 on, the photographs were normally taken outside the studio walls. When I went through these images, I discovered that one object is surprisingly often represented: a latticed wooden screen the Egyptians call mashrabiyah. It appears regularly as an ornamental backdrop, but sometimes also as an important element in the story.

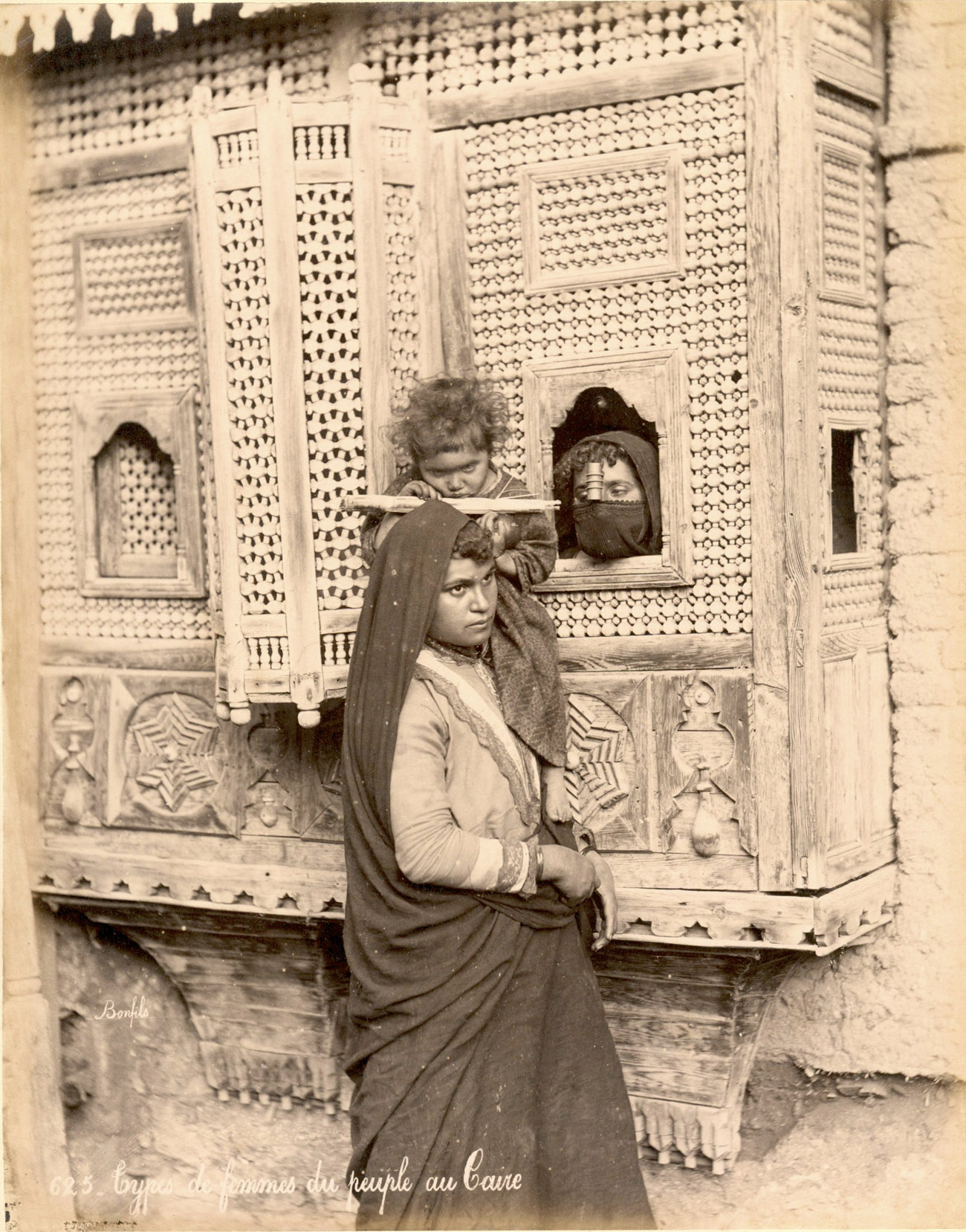

Types de femmes du people au Caire (Types of women from the people of Cairo), about 1880, Félix Bonfils. Personal collection of the author. Digital image courtesy of Felix Thürlemann

The traditional medieval quarters of the city of Cairo were characterized by this kind of construction, which adorned houses like oriels. The mashrabiyahs were attached to the rooms reserved for the inner circle of the family: the pasha and his wife or wives and children, the so-called harem. No male stranger was ever admitted to these rooms. The function of the mashrabiyah can be compared with that of a one-way mirror in our culture. It permits you to see out without being seen. The mashrabiyah screen allowed Egyptian women to observe life in the street or in the courtyard of the house without being perceived by any foreign male person. At the same time, it had two additional functions, important in the hot climate of Egypt: it provided shade and let the cooling air pass through.

Cairo street, about 1875, Zangaki Brothers. Albumen print mounted on period card, 20.5 x 27.7 cm. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.R.3. Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photography Collection

For a foreigner visiting Cairo, these screens with their refined workmanship—they are composed of small turned pieces of wood assembled according to traditional designs—were visually very attractive objects, but at the same time impenetrable to his eyes. Every screen stopped his view and entangled it in its complicated patterns. The tourist knew that behind each one, ‘real’ Egyptian family life took place; at times he felt he was being observed by someone behind the screen, but he couldn’t return the view. To fill the visual void, the westerner had to rely on his fantasies of harem life, for which opera libretti and novels offered, fortunately, enough material. For the photographer the same, of course, was also true.

If we compare nineteenth-century photographs showing scenes of everyday life with the documentary photographs of Cairo streets—most photographers produced works in both genres—we realize that the ones claiming to depict everyday life, like the photograph by Félix Bonfils above, are in fact completely staged. There was no reason for a woman to wear a veil inside the house. Moreover, it would have been impossible for her to see passers-by in the street at eye level, as the young woman with the child on her shoulder does. In reality, all the mashrabiyas were at least ten feet above street level.

In the staged scenes of foreign photographers, which were realized with the aid of paid individuals willing to be photographed, the mashrabiyah screen becomes to a certain extent permeable. Very often we see a person stretching his or her head through a small window, and sometimes even interacting with the people “in the street.” These images tried, in accordance with European values, to establish a kind of communication between the visible street life and the private life of the Egyptian people, although the latter remained to a large extent hidden, not only to foreigners but even to fellow Egyptians.

Femmes arabes sur Baudet (Arabic women on donkeys), about 1875, Zangaki Brothers. Unmounted albumen print, 20.5 x 27.7 cm. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.R.3. Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photography Collection

The little family scene by the Zangaki Brothers inscribed “Femmes arabes sur Baudet” (Arabic women on donkeys) is a characteristic example of this approach. We see two veiled women ready to depart from home. One of them sits on a grey ass conducted by a little black boy; the other, holding a child in her lap, on a white one. A girl stretches her head and right arm through a very small window inserted in the mashrabiyah screen of the house behind, probably to say goodbye to the company. This scene too, could never have happened like this in real life. It is enacted in an arranged artificial Cairo, whose elements, foremost the mashrabiyah fixed at much too low a level and the decorated door panel inserted in a vaulted niche, appear in dozens of other photographs signed “Zangaki.”

In effect, the Zangaki Brothers had, in the backyard of their studio in Cairo, built another, smaller Cairo, a kind of Arabian Disneyland composed of a few elements considered characteristic for the medieval city that the tourists were interested in—among them, of course, a mashrabiyah. Here, without being disturbed, they could stage their little stories with a small set of models who, on orders from the photographers, changed their clothes according to their changing roles.

And here’s another intriguing thing. When one looks closely at different photographs signed by different photographers working in Cairo, one discovers, again and again, an identical wooden screen. The mashrabiyah represented in the Bonfils picture reproduced above must be the exact same screen as the one we see in numerous Zangaki photographs. It is recognizable by a small little lacuna, a missing piece of turned wood, next to the window on the right. The Zangaki brothers, at a certain time, must have put their backyard studio at the disposition of their colleague Félix Bonfils from Beirut while he worked in Cairo to produce a set of genre photographs.

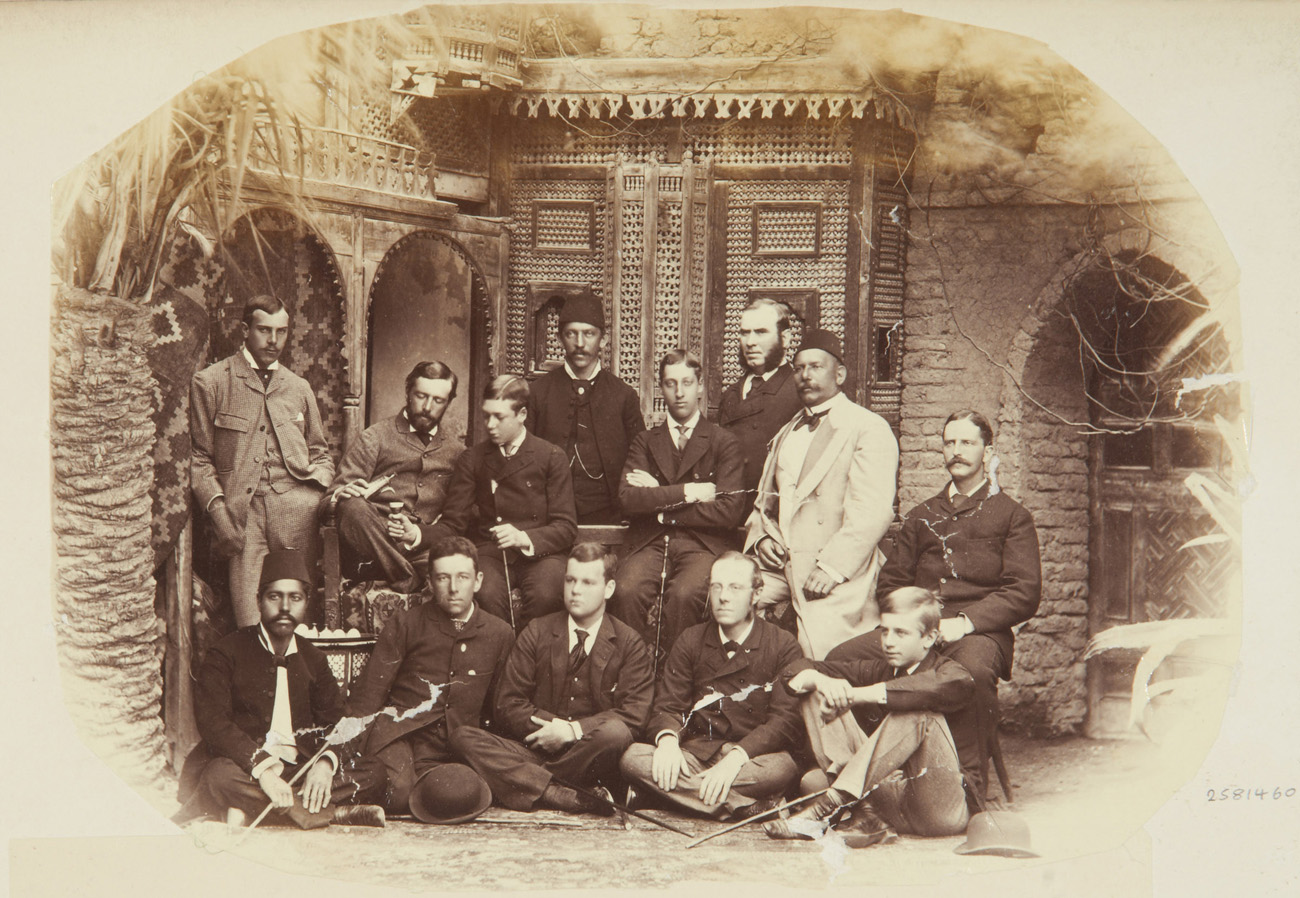

And the story does not end here. In early 1882 prince George, the future king of England, arrived with his brother Albert Victor and their escort in Cairo as the last station of a world tour on board the H.M.S. Bacchante. From the diary entry written by the princes, we learn that toward the end of their stay in the Egyptian capital, on March 22, the entourage of thirteen went to a photographer named “Schoeffet” to sit for a group photograph. The result still exists today, in two slightly different versions, in an album of the royal photographic collection housed in the Round Tower of Windsor Castle.

What a surprise: We know this place already! The photographer—his real name was Otto Schoefft—used, as a stage for his group portraits, the same Cairo-in-miniature employed by the Zangaki Brothers and then by Félix Bonfils. In the princely document, the mashrabiyah, together with some other characteristic architectural elements, has a precise function. It tells the viewer that the persons in the photograph have paid a visit to the land and to the monuments of Egypt.

Group portrait, “the party of the Bacchante,” datable to march 22, 1882, Otto Schoefft. Albumen print, 15.5 x 21 cm. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

This essay originally appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0)

Additional resources:

Felix Thürlemann, Das Haremsfenster (The Harem Window) (Wilhelm: Fink, 2019)