A rare night landscape

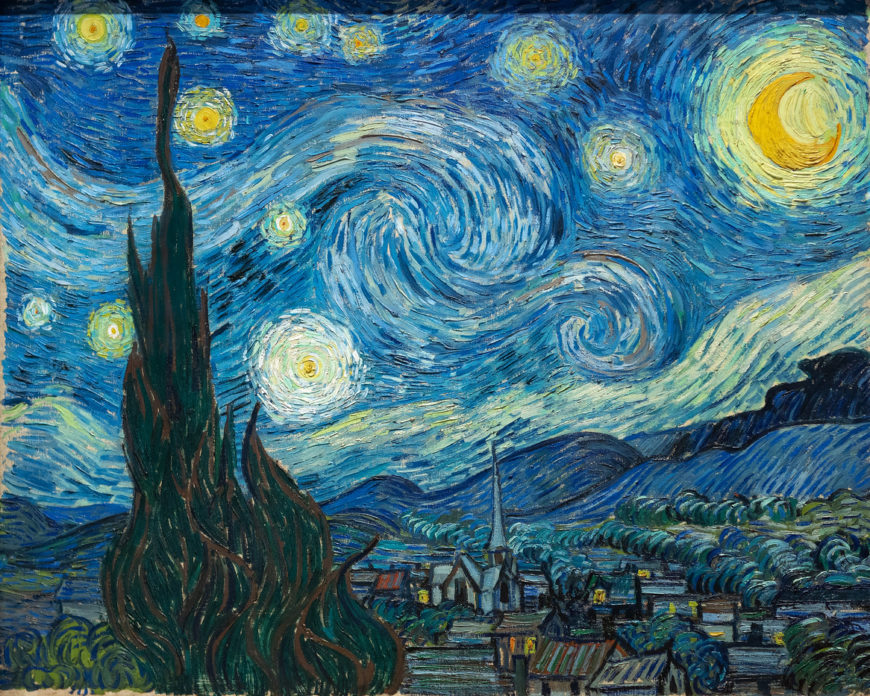

The curving, swirling lines of hills, mountains, and sky, the brilliantly contrasting blues and yellows, the large, flame-like cypress trees, and the thickly layered brushstrokes of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night are ingrained in the minds of many as an expression of the artist’s turbulent state-of-mind. Van Gogh’s canvas is indeed an exceptional work of art, not only in terms of its quality but also within the artist’s oeuvre, since in comparison to favored subjects like irises, sunflowers, or wheat fields, night landscapes are rare. Nevertheless, it is surprising that The Starry Night has become so well known. Van Gogh mentioned it briefly in his letters as a simple “study of night” or ”night effect.”

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

His brother Theo, manager of a Parisian art gallery and a gifted connoisseur of contemporary art, was unimpressed, telling Vincent, “I clearly sense what preoccupies you in the new canvases like the village in the moonlight… but I feel that the search for style takes away the real sentiment of things” (813, 22 October 1889). Although Theo van Gogh felt that the painting ultimately pushed style too far at the expense of true emotive substance, the work has become iconic of individualized expression in modern landscape painting.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night over the Rhone, 1888, oil on canvas, 72 x 92 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Technical challenges

Van Gogh had had the subject of a blue night sky dotted with yellow stars in mind for many months before he painted The Starry Night in late June or early July of 1889. It presented a few technical challenges he wished to confront—namely the use of contrasting color and the complications of painting en plein air (outdoors) at night—and he referenced it repeatedly in letters to family and friends as a promising if problematic theme. “A starry sky, for example, well – it’s a thing that I’d like to try to do,” Van Gogh confessed to the painter Emile Bernard in the spring of 1888, “but how to arrive at that unless I decide to work at home and from the imagination?” (596, 12 April 1888).

As an artist devoted to working whenever possible from prints and illustrations or outside in front of the landscape he was depicting, the idea of painting an invented scene from imagination troubled Van Gogh. When he did paint a first example of the full night sky in Starry Night over the Rhône (1888, oil on canvas, 72.5 x 92 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), an image of the French city of Arles at night, the work was completed outdoors with the help of gas lamplight, but evidence suggests that his second Starry Night was created largely if not exclusively in the studio.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Location

Following the dramatic end to his short-lived collaboration with the painter Paul Gauguin in Arles in 1888 and the infamous breakdown during which he mutilated part of his own ear, Van Gogh was ultimately hospitalized at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, an asylum and clinic for the mentally ill near the village of Saint-Rémy. During his convalescence there, Van Gogh was encouraged to paint, though he rarely ventured more than a few hundred yards from the asylum’s walls.

Saint-Paul-de-Mausole near Saint-Rémy, France (photo: Emdee, CC BY-SA 3.0)

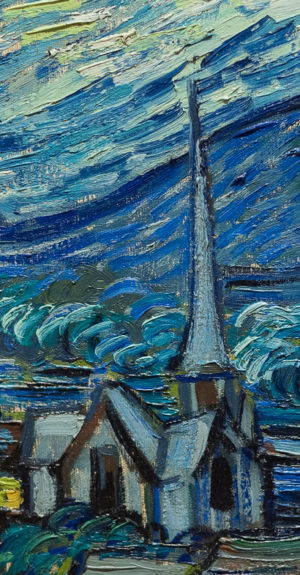

Church (detail), Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm. (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Besides his private room, from which he had a sweeping view of the mountain range of the Alpilles, he was also given a small studio for painting. Since this room did not look out upon the mountains but rather had a view of the asylum’s garden, it is assumed that Van Gogh composed The Starry Night using elements of a few previously completed works still stored in his studio, as well as aspects from imagination and memory. It has even been argued that the church’s spire in the village is somehow more Dutch in character and must have been painted as an amalgamation of several different church spires that van Gogh had depicted years earlier while living in the Netherlands.

Van Gogh also understood the painting to be an exercise in deliberate stylization, telling his brother, “These are exaggerations from the point of view of arrangement, their lines are contorted like those of ancient woodcuts” (805, c. 20 September 1889). Similar to his friends Bernard and Gauguin, van Gogh was experimenting with a style inspired in part by medieval woodcuts, with their thick outlines and simplified forms.

Stars (detail), Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The colors of the night sky

On the other hand, The Starry Night evidences Van Gogh’s extended observation of the night sky. After leaving Paris for more rural areas in southern France, Van Gogh was able to spend hours contemplating the stars without interference from gas or electric city street lights, which were increasingly in use by the late nineteenth century. “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big” 777, c. 31 May – 6 June 1889). As he wrote to his sister Willemien van Gogh from Arles,

It often seems to me that the night is even more richly colored than the day, colored with the most intense violets, blues and greens. If you look carefully, you’ll see that some stars are lemony, others have a pink, green, forget-me-not blue glow. And without laboring the point, it’s clear to paint a starry sky it’s not nearly enough to put white spots on blue-black. (678, 14 September 1888)

Van Gogh followed his own advice, and his canvas demonstrates the wide variety of colors he perceived on clear nights.

Invention, remembrance and observation

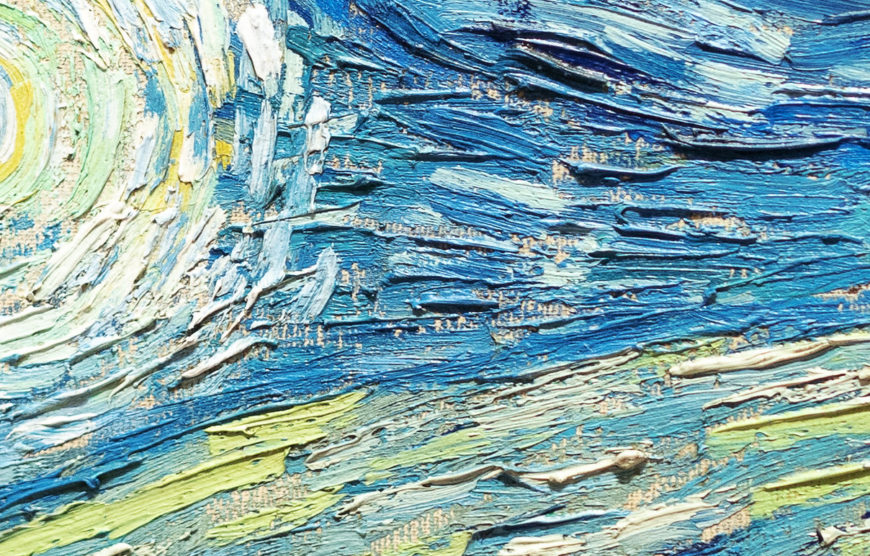

Impasto and brush strokes (detail), Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Arguably, it is this rich mixture of invention, remembrance, and observation combined with Van Gogh’s use of simplified forms, thick impasto, and boldly contrasting colors that has made the work so compelling to subsequent generations of viewers as well as to other artists. Inspiring and encouraging others is precisely what Van Gogh sought to achieve with his night scenes. When Starry Night over the Rhône was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, an important and influential venue for vanguard artists in Paris, in 1889, Vincent told Theo he hoped that it “might give others the idea of doing night effects better than I do.” The Starry Night, his own subsequent “night effect,” became a foundational image for Expressionism as well as perhaps the most famous painting in Van Gogh’s oeuvre.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Google Art Project

The Starry Night from MoMA Multimedia

This painting from MoMA Learning

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”VGSN,”]