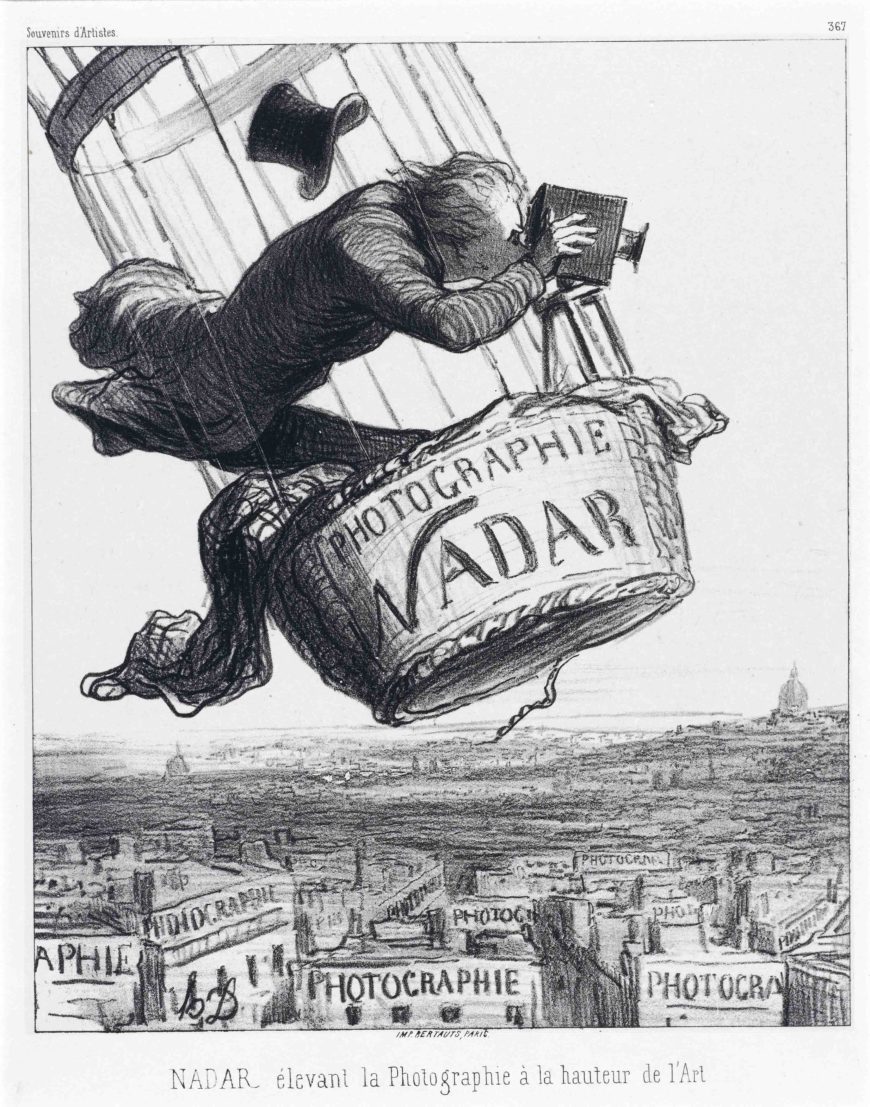

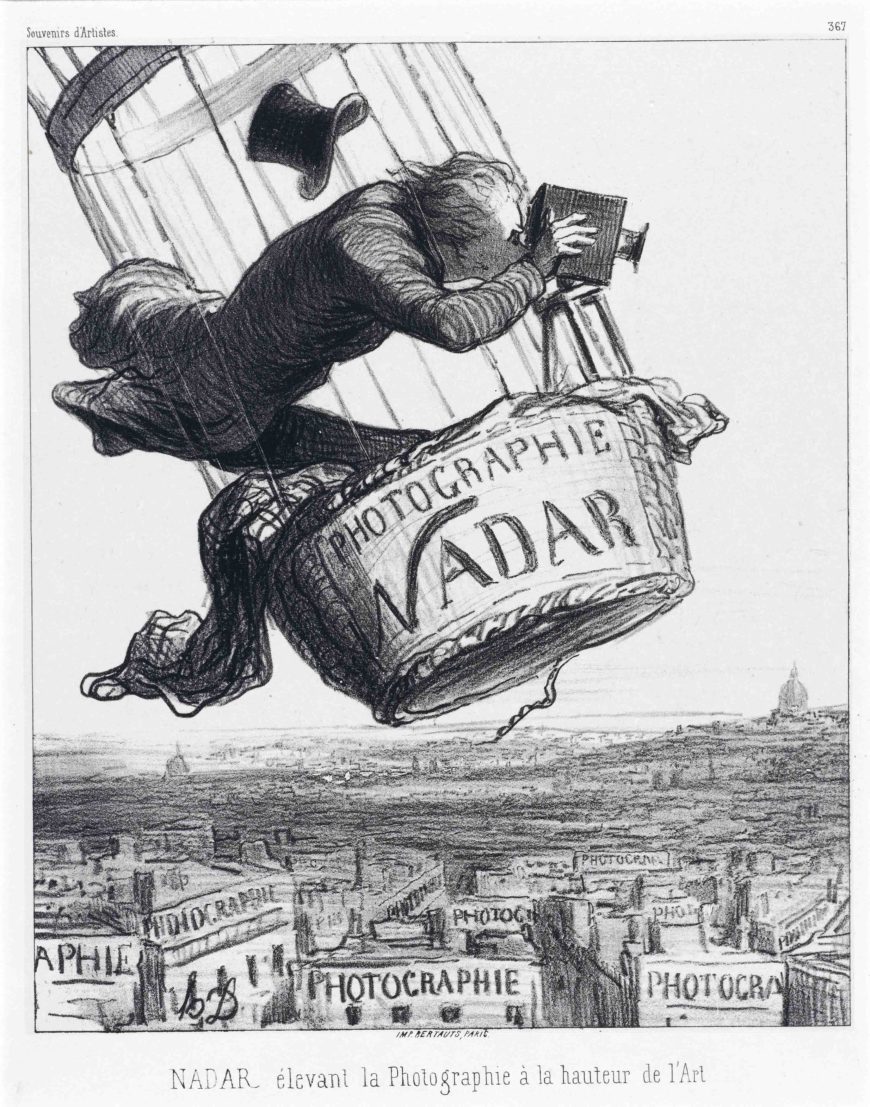

Honoré Daumier, Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of an Art, 1862, lithograph from Souvenirs d’Artistes, 44.8 × 30.9 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Elevating photography

When Honoré Daumier immortalized Nadar—famed photographer, writer, and caricaturist—photographing wildly while aloft in his hot air balloon in 1862, photography was just 23 years old. The invention of the daguerreotype had been announced in Paris in 1839. Although immensely popular in its early years, it was not reproducible and was eventually replaced in the 1850s by the new albumen process, which promised both fidelity to nature and the possibility of multiple prints.

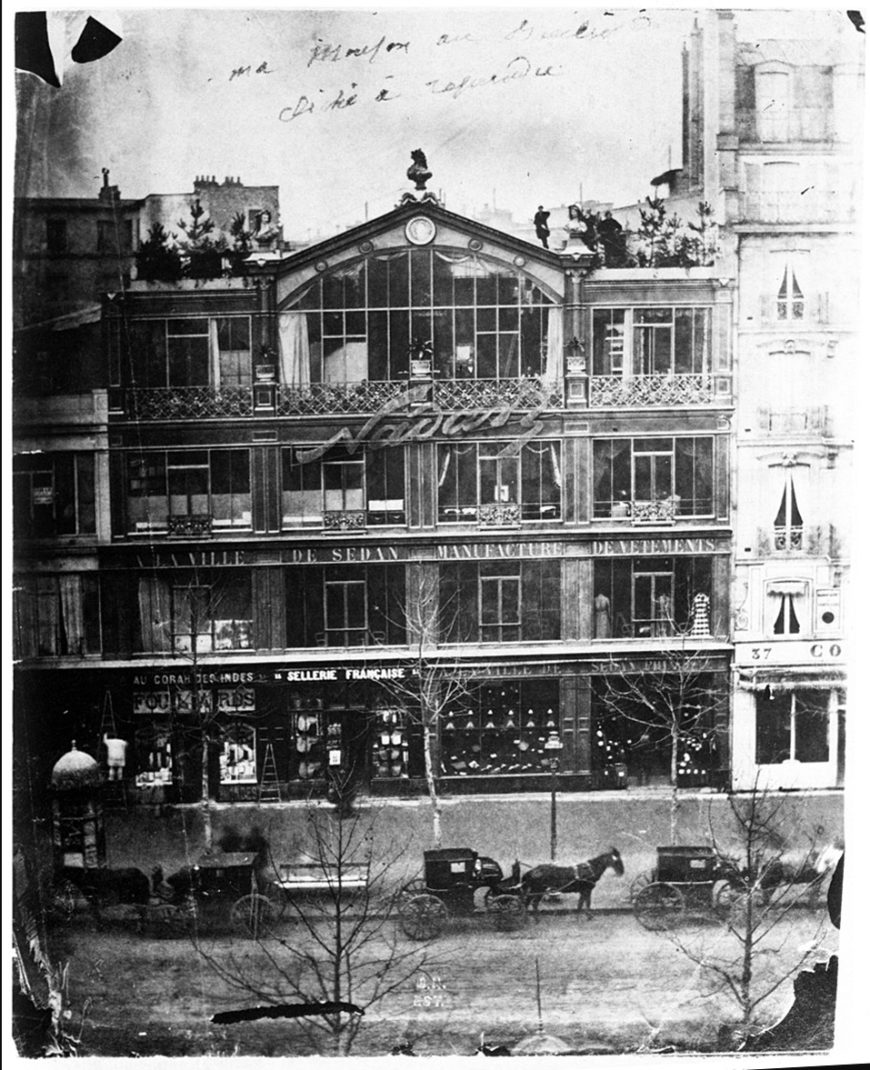

Despite the medium’s infancy, Daumier’s lithograph leads the viewer to believe that 1862 Paris was teeming with photography studios (suggested by the word “Photographie” on nearly every visible building façade). And this was only a small exaggeration as there were approximately 400 photography studios operating in Paris by the end of the 1860s. We are to assume, then, that photography and photography studios so inundated Second Empire Paris that Nadar has taken to the air to one-up his photographic rivals. He is so enraptured by this aerial feat that he is oblivious to the viewer’s presence and the gust of wind that has removed his hat. The balloon, which seems to barely contain the enthusiastic photographer, is adorned with the phrase “Photographie Nadar” in the same cursive script that appeared on the façade of his lavish studio on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. This is a reminder to the 19th-century viewer that Nadar’s concerns were as much about self-promotion as they were about the status of photography. From his aerial position high above the streets of Paris, Nadar has undoubtedly elevated photography, but how has he succeeded, as Daumier tells us in his caption, at elevating photography to an art?

What’s in a name?

Nadar, born Gaspard-Félix Tournachon in Paris in 1820, changed his name in his youth as an expression of his rebellious streak that stayed with him throughout his life. Although his name change might seem unremarkable, for Nadar his name was attached not only to his art, but also to a persona that he worked hard to cultivate. The name “Nadar” was the name he had chosen for himself and the name he later went to court to keep. When his brother Adrien, whose struggling photography studio Nadar had helped to save from financial ruin, began using the name “Nadar” to sell photographs and portrait sittings (even changing the name of the studio to “Tournachon Nadar and Company”) Nadar went to court to defend his exclusive right to the name “Nadar.”

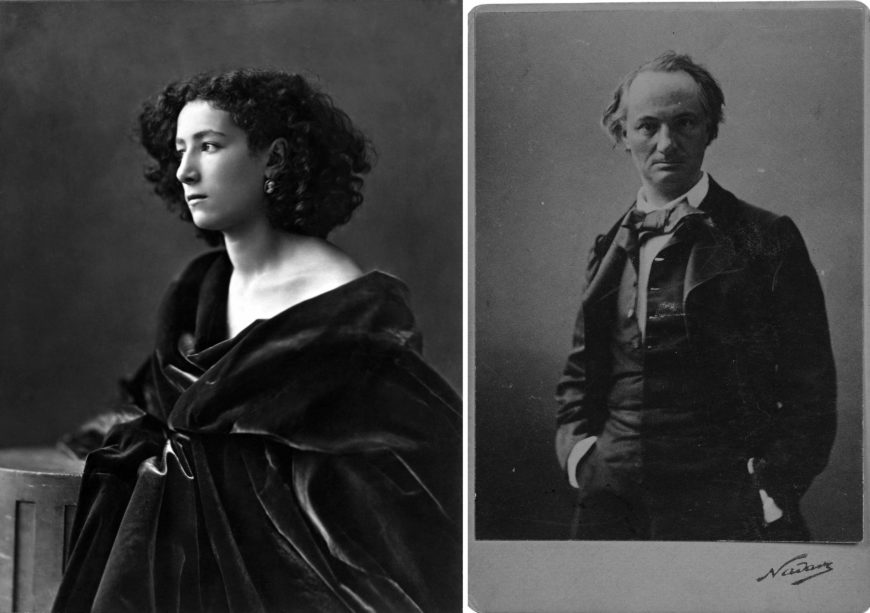

Left: Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt, 1864, gelatin silver print, 21.2 x 16.2 cm (Getty Center); right: Nadar, Charles Baudelaire, 1855 (public domain)

In his statement to the court, the renowned portraitist, who photographed such celebrities as actress Sarah Bernhardt, novelist Georges Sand, poet Charles Baudelaire, and countless others, made clear that the name “Nadar” was synonymous with art rather than industry: “What can’t be learned [about photography], it’s the sense of light, it’s the artistic appreciation of the effects produced by different and combined qualities of light, it’s the applying of this or that effect according to the nature of the face that you have to reproduce as an artist.” [1]

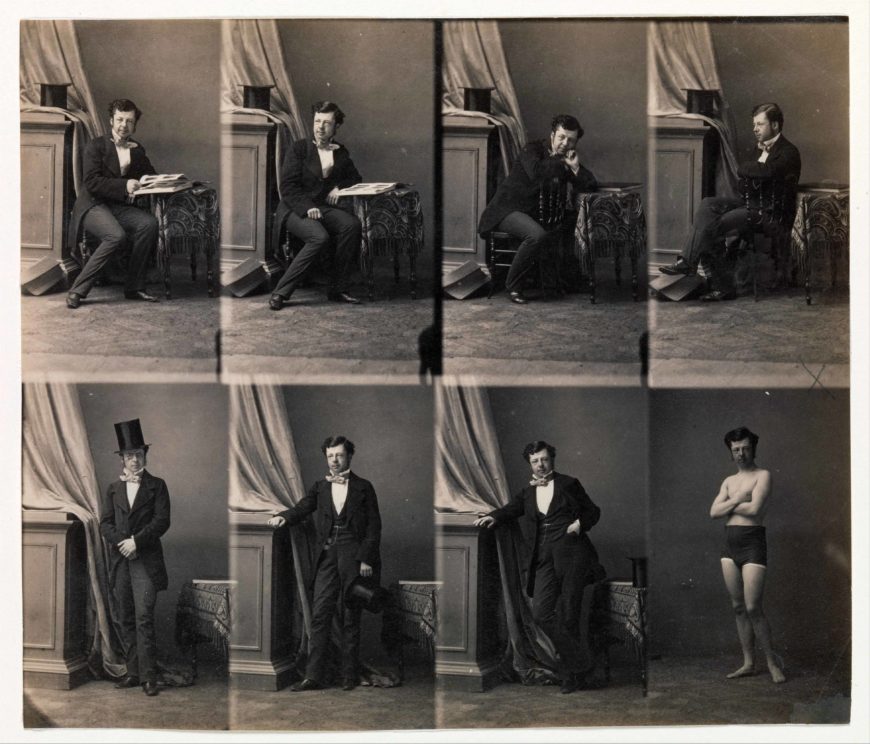

The carte-de-visite, developed by Disdéri, revolutionized photographic portraiture as a quick and mass producible medium. Made in a camera with multiple lenses, the resulting carte-de-visite images were cut and pasted to small cards. This new, faster, and less expensive approach to portraiture allowed for different poses, props, and backgrounds, and was arguably more concerned with industry than art. André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, Prince Lobkowitz, 1858, carte-de-visite, albumen silver print from glass negative, 20.0 x 23.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

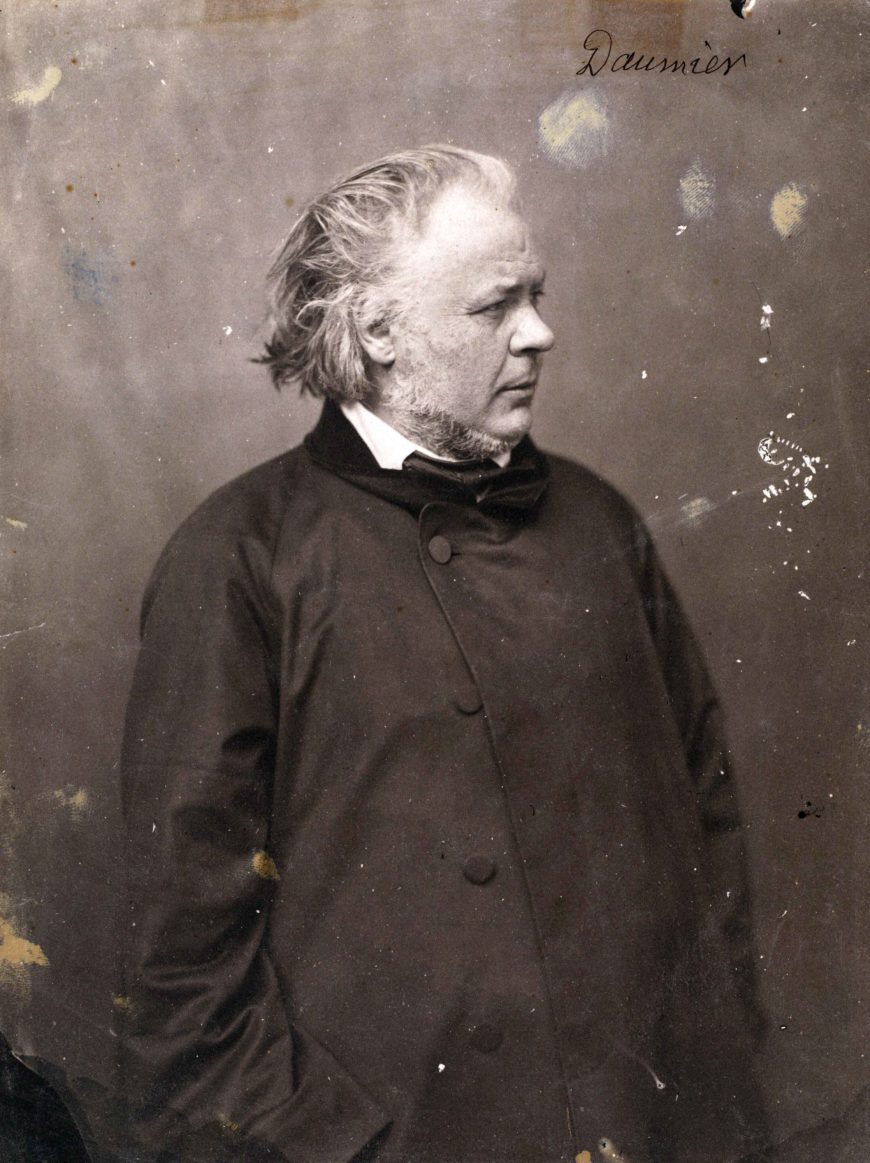

Nadar, Honoré Daumier, 1856–58, salt print from glass negative, 24.4 x 17.9 cm (National Gallery of Art)

So, almost from the start of his photographic career, Nadar equated his work with art rather than industry or science, thus differentiating it from the workaday products of most Parisian photography studios (the very same studios Nadar soars over in Daumier’s print). As demonstrated in his portrait of actress Sarah Bernhardt or his portrait of Daumier, Nadar’s photographic portraits broke many of the rules of traditional studio photography: he worked with larger plates, charged more for his prints, made minimal use of props, used strong lighting, and posed his sitters in such a way as to capture their personality. He also cultivated a bohemian and celebrity clientele. In his emphasis on creativity and those factors that defined his practice as a portrait photographer, he was making the argument that photography could indeed be an art.

Art vs. industry

In the 1850s, a growing divide emerged between those who viewed photography as an art and those who viewed it as an industry (or profession). This period saw, perhaps not surprisingly, the beginnings of a commercial photography boom that brought both artists and entrepreneurs to the new medium. As a technical medium made possible by a thorough knowledge of chemistry and processes, photography could be learned and, standardized. But that did not necessarily translate to artistic expression.

Charles Baudelaire famously referred to the photographic craze of the 1850s as “industrial madness,” believing that photography amounted to little more than a servile representation of nature and that, if allowed to continue unchecked, could easily corrupt high art as the domain of beauty and imagination. [2] Nadar himself was unconvinced; speaking in 1856, he asserted: “Photography today is more than a science: It has raised itself to the heights of art.” [3] For Nadar, this meant not just capturing a likeness, but capturing something of the personality and attitude of his sitters, a skill he cultivated as a caricaturist.

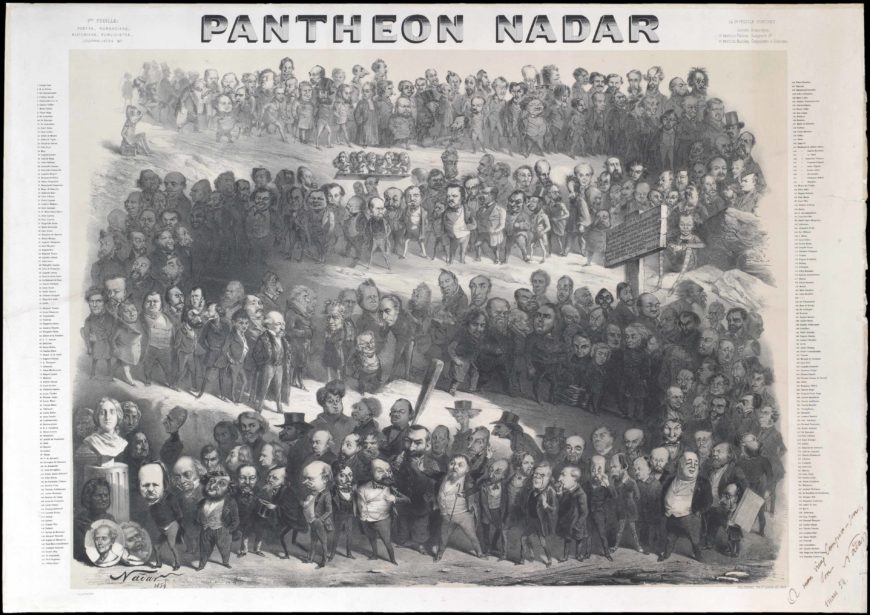

Nadar, Nadar’s Pantheon (Panthéon Nadar), 1854, lithograph, 81.9 x 114.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

His lithograph Panthéon Nadar (Nadar’s Pantheon), the culmination of his work as a caricaturist, included 250 caricatures of prominent Parisian authors, all with identifying characteristics and exaggerated expressions. It was this interest in the psychology of his subjects (and with celebrity) that ultimately brought Nadar to portrait photography. It would surely also have interested Nadar that lithography and photography were new industrial techniques with far-reaching artistic potential when properly exploited.

Daumier and the satirical press

Honoré Daumier, Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of an Art, 1862, lithograph from Souvenirs d’Artistes, 44.8 × 30.9 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Famed painter, sculptor, and printmaker, Honoré Daumier was a progressive working-class artist who came to prominence in the 1830s with his bitingly satirical prints (lithographs) that took on everything from politics and the powerful to commentaries on Parisian society and the state of the arts. Daumier was a longtime contributor to the satirical anti-monarchist journal Le Charivari, which published mocking caricatures of everyday life even after the 1835 ban on political satire. He left Le Charivari in 1860, and subsequently created a series of lithographs for his friend Etienne Carjat’s short-lived illustrated newspaper, Le Boulevard. An important reflection of Second Empire Paris, Le Boulevard included texts and illustrations by some of the most renowned artists and writers of the day—Charles Baudelaire, Victor Hugo, Champfleury, Daumier, and Gustave Doré, among them. Delivered to the publisher as lithographic stones, Daumier’s illustrations for Le Boulevard included several humorous observations about the current state of the arts in Paris.

Daumier’s Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of an Art was among the now famous lithographs published by Le Boulevard in the early 1860s. With characteristic wit, Daumier refers not only to Nadar’s literal elevation of photography and his championing of the artistic possibilities of the medium, but also the recent court decision that recognized photography as an art (and thus subject to the same copyright restrictions as other established fine arts).

![Nadar, [Nadar with His Wife, Ernestine, in a Balloon in his studio], ca. 1865, printed 1890s.](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/nadar-balloon-870x1000.jpg)

Nadar, [Nadar with His Wife, Ernestine, in a Balloon in his studio], c. 1865, printed 1890s, gelatin silver print from glass negative, 9 x 7.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Notes:

[1] Nadar quoted in: Maria Morris Hambourg, Nadar (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995), p. 25.

[2] Charles Baudelaire, “Photography” (1859), reprinted in Beaumont Newhall, ed., Photography: Essays & Images (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1980), pp. 112–113.

[3] Nadar quoted in: Anne McCauley, Industrial Madness: Commercial Photography in Paris, 1848–1871 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), p. 120.

Additional resources

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, “The Nadars, a Photographic Legend”

Maria Morris Hambourg, Nadar (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995).