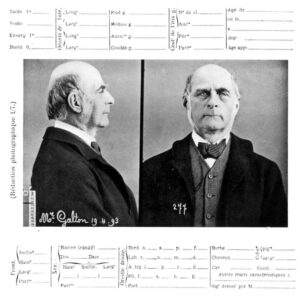

This identity card, consisting of profile and frontal portrait photographs, paired with the dimensions of various parts of the subject’s body, was among thousands used by police stations in France, Great Britain, Germany, and the United States in the late nineteenth century to help police and victims identify repeat offenders. It featured (but was not limited to) measurements of the offender’s height, age, arm span and arm length, the shape of their heads, ears, noses, foreheads, lips, the length of the middle finger, as well as their eye color and iris patterns, in addition to any peculiar identifying characteristics such as birthmarks or scars.

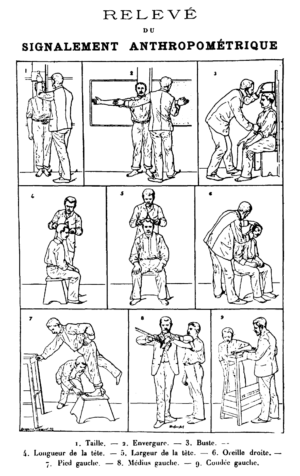

These illustrations instruct law-enforcement officials on the proper collection of several measurements for Bertillon’s anthropometric identification system. The accuracy of the system depended on uniform approaches to collecting these biometrics. Alphonse Bertillon, Frontispiece of Identification Anthropométrique: Instructions Signalétiques (1893).

Developed by French police officer Alphonse Bertillon in the 1870s, and published as a book in 1893, the “Bertillon System” paired anthropometric measurements with “mug shots,” police booking photographs featuring a shoulder-up views of the front and side of a subject before a plain background. [1] Bertillon—who was from a family of respected statisticians—hypothesized that no two people likely shared the same body proportions and appearance, and he suggested that the combination of photographs and dozens of body measurements would help identify frequent criminals with greater accuracy than other methods—such as the “mug shot” alone, or fingerprinting (then an emerging approach to criminal identification). [2] Within ten years of testing his system in Paris (in advance of its publication), an additional 5,000 repeat criminals had been identified using the Bertillon System [3]. Pickpocketing incidents fell dramatically in Paris, a decline attributed to Bertillon. [4] The system was deemed not only a successful means for identifying criminals but was declared such an effective crime deterrent that police departments in Belgium, a destination for Paris’s wayward pickpockets, quickly adopted it. [5]

Approaches to human classification

Before developing his “mug shot”/anthropometric system, Bertillon, who worked in 1879 as an Assistant Clerk for the Paris Police, copied verbal descriptions of criminals onto index cards, and found that job not only tedious, but lacking in tangible specificity when it came to describing human appearances. He turned to photography to help provide a more “signaletic,” subjectivity-free, accurate, visually specific, description of the criminals than words alone could convey. “Mug shot” daguerreotypes were first made and used by law-enforcement agencies as early as the mid-to-late 1840s in Belgium and England, just a few years after the invention of photography was announced to the world in 1839. [6] From the origins of the medium, its ability to capture human likenesses was noted, celebrated, and harnessed for various fields of science, including anthropology and criminology. It enabled the creation of archives of multiple images for the purpose of studying photographic subjects’ commonalities and differences.

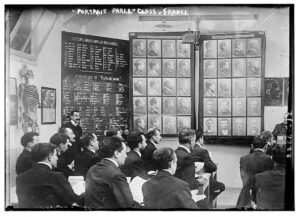

In his system, Bertillon combined the “mug shot” photographs with objective biometrics to capitalize on the strengths of verbal description, body measurements, and photography’s ability to describe the external appearances of subjects with what he argued was a high degree of fidelity. Over time, the combination of fingerprinting, a smaller set of body measurements, and the “mug shots” have remained a part of criminal identification by law-enforcement worldwide. A similar combination of words, measurements, and “mug shots” evolved as the standard for state and national identification cards, driver’s licenses, and passports—all of which have expanded governments’ archives far beyond police files to include almost all adult citizens.

Photographer Unknown, Class on the Bertillon System, France, 1911 (Library of Congress)

Defining Criminal “Types”: Galton, eugenics, and Bertillonage

Photography’s utility for creating an archive for identifying human “types,” or “typologies,” was noted by photographer and theorist Allan Sekula, who wrote that this use of the medium was especially common in the late nineteenth century, due to the popular pseudo-sciences of physiognomy and phrenology. [7] Physiognomy (assessing a person’s character from their outer appearance) and phrenology (measuring bumps on the skull to predict the mental capacities of the subjects) gave Victorian-era scientists license to use Bertillon’s system to discriminate against photographic subjects on the basis of their appearance, race, gender, economic position, and more. Although Bertillon acknowledged that it might be dangerous for his system to be used to predetermine the physical appearances of criminals and more carefully police a particular constituency—something we today might call “stereotyping” or “racial profiling”—his archive was of great interest to others who were eager to put it to use in that way. [8] In Minneapolis, a disproportionate number of Black women were cataloged using Bertillon’s system from 1915–19, were far more frequently charged and sentenced to a work house for being “alley workers,” or prostitutes, than their white counterparts. Comments on one suspect’s police record reveal the anti-Black racist attitudes that prevailed in the early 20th century: “[She was] one of the numerous colored women who infest south Minneapolis, robbing white men in alleys, etc.” [9]

The subject of Bertillon’s identification card, Francis Galton, was a respected founder of the Eugenics movement, which advocated for the select breeding of only those people who possessed desirable hereditary traits (being white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant—the same background as most the eugenicists). Galton used photography to help provide visual examples of corresponding mental and moral qualities (both positive and negative), as he simultaneously advocated for the Bertillon system. Photography allowed Galton to give enduring, tangible, visual form to “generic mental images,” or the mental impressions we form about groups of people—perhaps better known as “stereotypes.” [10]

Francis Galton, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development (Frontispiece of Book) (detail), 1883, albumen silver print from glass negative, 20 x 11/8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

For example, in the 1883 book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, Galton superimposed the “mug shots” of eight men (see top portrait, right) and four (see bottom portrait, right) arrested men to create a composite image that gave tangible visual form to the stereotype of the “criminal,” so those types of individuals could be physically identified, avoided, and “Othered” by society as moral deviants. Galton’s ideas were furthered by Italian physician and criminologist Cesare Lombroso, who suggested that criminality was an inborn characteristic with physical markers that included a large jaw, a sloping forehead, an asymmetrical face or head, unusually large or small ears, a flattened, hawkish, or upturned nose, fleshy lips, high cheekbones, hard shifty eyes, long arms, inherited moles or birthmarks, a light beard or baldness, physical defects, and other physical deviances from the statistical norm promoted by eugenicists. Lombroso’s findings—as well as physiognomy, phrenology, and the Eugenics movement—were gradually debunked and generally dismissed as settled science by the late 1930s, but implicit biases in policing based on people’s outward appearances’ connections to inner morality and character have survived.

Notes:

[1] Alphonse Bertillon, Identification Anthropométrique: Instructions Signalétiques (Geneva: Melun Administrative Printing, 1893). For a vivid description of the use of Bertillon’s system, please see: Ida M. Tarbell, “Identification of Criminals: The Scientific Method in Use in France,” McClure’s Magazine, Vol. 2, Issue 4 (March 1894): pp. 355–69.

[2] Nicolas Quinche and Margot Pierre, “Paul-Jean Coulier (1824-1890): A Precursor in the History of Fingermark Detection and Their Potential Use for Identifying Their Source,” Journal of Forensic Identification, Vol. 60, Issue 2 (March/April 2010): pp. 129–134.

[3] Tarbell, “Identification of Criminals…,” p. 368.

[4] Tarbell, “Identification of Criminals…,” p. 368.

[5] Tarbell, “Identification of Criminals…,” p. 368.

[6] Randy Kennedy, “Grifters and Goons, Framed (and Matted),” The New York Times (Sept. 15, 2006). Accessed Jan. 2, 2023.

[7] Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October, No. 39 (1986): p. 3.

[8] Tarbell, “Identification of Criminals…,” p. 369.

[9] “Frances McRaven,” Bertillon Ledgers, Tower Archives, Minneapolis City Hall, Minneapolis, MN.

[10] Francis Galton, Generic Images (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1879), p. 166.

Additional resources

Kris Belden-Adams, Eugenics, ‘Aristogenics,’ Photography: Picturing Privilege (New York: Routledge, 2020).

Elizabeth Edwards, “Evolving Images: Photography, Race and Popular Darwinism,” in D. Donald and J. Munro, eds. Endless Forms, Darwin, Natural Sciences and the Visual Arts (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2009), pp 166–93.

Anne Maxwell, Picture Imperfect: Photography and Eugenics, 1879–1940 (East Sussex, U.K.: Sussex Academic Press, 2008).

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October, No. 39 (1986): p. 3.

Ida M. Tarbell, “Identification of Criminals: The Scientific Method in Use in France,” McClure’s Magazine, Vol. 2, Issue 4 (March 1894): pp. 355–69.