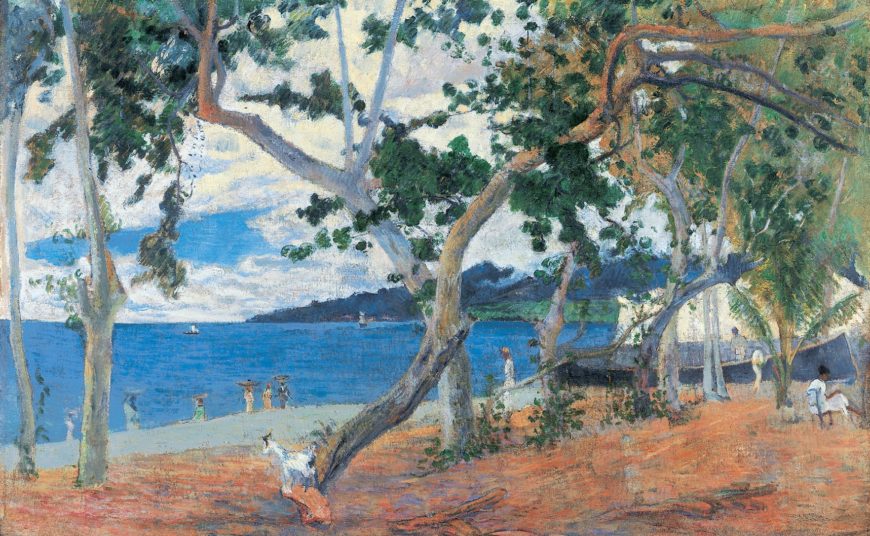

Paul Gauguin, Coastal Landscape From Martinique (The Bay of St.-Pierre, Martinique), 1887, oil on canvas, 50 × 90 cm (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen)

When you think of Paul Gauguin, you probably think of exoticized visions of the South Pacific or colorful scenes of the Breton countryside. What you most likely do not immediately think of is the Caribbean. However, before he painted famous works like Vision after the Sermon and Spirit of the Dead Watching, the artist spent several months in Martinique, a French possession in the Lesser Antilles. While on the island, Gauguin painted numerous works that portray Martinique as a lush landscape filled with local women and tropical fruits. These colorful works provide an unexpected link to Caribbean art and can serve as a case study in the history of travel and depictions of Martinique in the nineteenth century.

From Panama to Martinique

Gauguin’s journey began on April 10, 1887, when he and his friend Charles Laval boarded the steamship Canada heading for Panama. Both were artists searching for something new, beyond what they viewed as the constraints of modern life in France. Gauguin—whose finances were running low—was particularly fed up with life in Paris, which he called “a desert for a poor man.”[1]

In Panama, the pair hoped to find employment that would offer them new horizons in which to create. Unfortunately, Panama did not match their idealistic expectations: the landscape had been drastically altered by the construction of the Panama Canal, disease was rampant, and stable work was hard to find. After many difficult weeks, Gauguin and Laval left Panama for Martinique hoping to find more ideal conditions. They arrived on June 11, 1887 and rented a hut on a sugar plantation, near the island’s cultural and economic capital of Saint-Pierre.

People, Fruits, and Landscapes

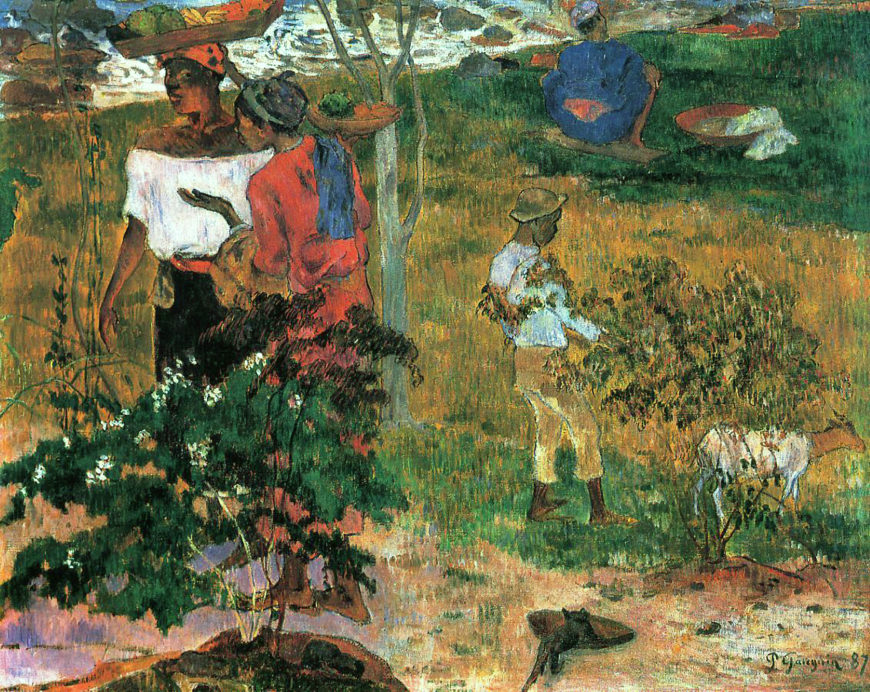

Although they were close to the city, the two artists focused on the tropical landscape, as seen in Gauguin’s The Mango Trees, Martinique. Here, Gauguin depicts a group of women picking fruit in a grove of trees. Gauguin uses short strokes and varying shades of green and orange to paint the tropical vegetation which includes a recognizable papaya tree in the left foreground. The women wear traditional clothing: long, loose dresses or skirts, beaded necklaces, and madras headscarves.

Paul Gauguin, The Mango Trees, Martinique, 1887, oil on canvas, 86 × 116 cm (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam)

All of the figures in the scene are of African descent, reflecting a major demographic on the island. Like many Caribbean islands, Martinique was shaped by a plantation economy fueled by the forced labor of people who were kidnapped and transported from Africa during the transatlantic slave trade. Although slavery was abolished in 1848, descendants of enslaved people formed a large part of the island’s working class, including plantation workers, who worked alongside new arrivals from Africa and Asia in often wretched conditions.

Near the center of the composition, a woman balances a basket on her head, a practice that fascinated those visiting the Caribbean. In Martinique, the women who carried goods from the countryside to markets this way were known as porteuses. These women were a popular subject for artists and writers traveling to Martinique—including Gauguin and Laval. Because of where they lived, the artists would have seen many local women picking fruits or passing through on their way to Saint-Pierre.

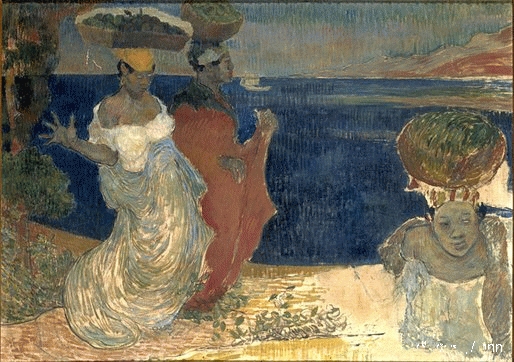

Charles Laval’s Women by the Sea also shows a group of porteuses walking along the coast. As in The Mango Trees, the women in the scene wear traditional dresses, skirts, and headscarves. Rather than a grove of trees, Laval provides a clear view of the Bay of Saint-Pierre with the Mount Pelée volcano rising in the distance. Laval also builds his composition using directional strokes of paint, but animates his figures in a more dramatic way. The porteuse on the left extends her forearm and fingers, while her tray of fruits bends under its own weight—a contrast to Gauguin’s peaceful figures.

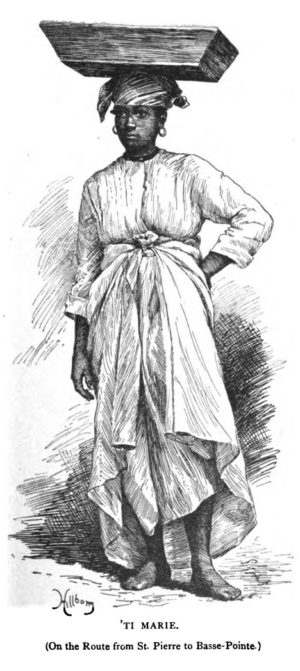

“‘Ti Marie,” engraving in Lafcadio Hearn, Two Years in the French West Indies (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1890), p. 107.

Idealized Caribbean Labor

A common element in Gauguin and Laval’s work in Martinique is the depiction of working Afro-Caribbean women—notably porteuses. Although they certainly were a part of contemporary Martinique, both artists overwhelmingly favored them in their paintings. A recent exhibition catalogue noted that the artists created a vision of an island inhabited almost entirely by porteuses.[2]

Images of these figures were popular well before Gauguin and Laval arrived. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century painters depicted porteuses in bustling cityscapes and as staffage (small figures included in landscape paintings, often to mark scale) in picturesque views for elite local patrons and audiences in France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Caribbean travel books and magazines featured images of porteuses in their illustrations, which were seen by thousands of readers in France and the United States. Two Years in the French West Indies (published in 1890) by American travel writer Lafcadio Hearn included an entire chapter on porteuses, which featured an engraved illustration. Like the figures depicted by Gauguin and Laval, the barefoot woman wears a loose, long dress, madras turban, and balances a tray on her head.

The popularity of porteuses may be due to the unfamiliar and seemingly idealized nature of their labor. Although in reality they travelled dozens of miles along mountainous paths with heavy loads on their heads, porteuses could be viewed as independent workers in harmony with nature—arguably heightened by the animals in the compositions. Compared to depictions of work on sugar plantations—which incidentally are largely absent from images depicting Martinique—the porteuses offered a female subject that would please audiences and cast the island as an exotic idyll.

Gauguin, Laval, and the Conventions of Depicting Martinique

Although Gauguin and Laval adhered to certain conventions of depicting Martinique, their work also stands out. The artists’ chose to focus exclusively on Afro-Martiniquan people. Many paintings, photographs, and engravings emphasized the ethnic diversity on the island, especially varying shades of skin tone. Illustrated books often featured images of different (mostly female) “ethnic types,” from dark-skinned negresses to light-skinned mulâtresses (note that these terms have derogatory connotations in English, but are more descriptive—if still problematic—in a French Caribbean context). In contrast, Gauguin and Laval largely avoided the depiction of different racial “types” and depicted an exclusively dark-skinned population. Whether this was a conscious choice or for another reason, the artists’ figures go beyond the tradition of the ethnic showcase.

While Gauguin’s choice to focus on women is hardly surprising, the fact that the figures are not blatantly eroticized is also significant, given the artist’s reputation. Unlike the lounging, nude figures Gauguin later painted in Tahiti, the Martiniquan figures are fully clothed, working women. In the Martinique landscape paintings, they seem to inhabit a tropical Arcadia that are also genre scenes depicting work and rest.

Paul Gauguin, Coming and Going, Martinique, 1887, oil on canvas, 72.5 × 92 cm (Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

Conclusion

Gauguin and Laval’s journey to Martinique is a lesser-known chapter in the history of nineteenth-century French painting that connects to the country’s Caribbean colonies. Like many artists who travelled to Martinique, the two artists depicted porteuses and lush tropical landscapes. However, the unique style of their works, as well as their nearly exclusive focus on Afro-Caribbean figures stands out. While Gauguin will likely continue to be remembered for his colorful (and increasingly problematized) views of the Pacific, maybe next time you hear his name you’ll think of a small French island in the Caribbean.

Notes:

- Paul Gauguin, Letters to His Wife and Friends, ed. Maurice Malingue, trans. Henry J. Stenning (Boston: MFA Publications, 2003), p. 75.

- Joost van der Hoeven, “Martinique Experienced,” Gauguin and Laval in Martinique (Bussum: Thoth Publishers, 2018), p. 68.

Additional Resources

“Gauguin and Laval in Martinique,” Van Gogh Museum

Maite van Dijk, Joost van der Hoeven, et al. Gauguin and Laval in Martinique (Bussum: Thoth Publishers, 2018).

Paul Gauguin, Letters to His Wife and Friends, ed. Maurice Malingue, trans. Henry J. Stenning (Boston: MFA Publications, 2003).

Lafcadio Hearn, Two Years in the French West Indies (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1890).

Kay Dian Kriz, Slavery, Sugar, and the Culture of Refinement: Picturing the British West Indies, 1700–1840 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

Joost van der Hoeven, “Martinique Experienced,” Gauguin and Laval in Martinique (Bussum: Thoth Publishers, 2018), pp. 58–75.