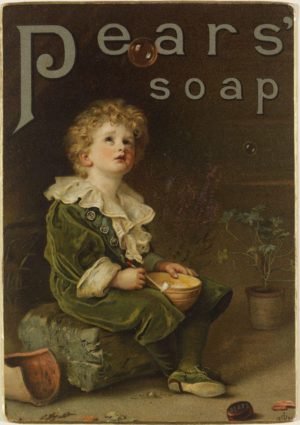

John Everett Millais, Bubbles, 1886, oil on canvas (Unilever, on long loan to Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool)

The innocence of childhood

Victorian art is often dismissed as an overly sentimental and cutesy style of painting, and nowhere are these qualities more apparent than in Bubbles by John Everett Millais. Painted in 1886, Bubbles captures the innocence of childhood with all the technical mastery of a mature and talented artist. But the painting also raises questions about the importance of serious subject matter, Victorian taste, and the relationship between art and advertising in the 19th century.

Jean Siméon Chardin, Soap Bubbles, c. 1733–34, oil on canvas, 61 x 63.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bubbles is in fact a portrait of Millais’s four-year-old grandson William Milbourne James. According to the artist’s biography written by his son J.G. Millais, the picture was produced “simply and solely for his own pleasure. He was very fond of his little grandson Willie James — a singularly beautiful and most winning child — and seeing him one day blowing soap bubbles through a pipe, he thought what a dainty picture he would make.” [1]

In the painting the angelic looking, red-cheeked young boy looks up at the floating bubbles, his blond curls creating a halo around his head. Seated in a dingy, non-descript background, he is dressed in a velvet suit with a ruffled lace collar, not the most practical clothing for a small boy. The various textures in the painting are beautifully recreated, as is the bubble, which the biography says was created with a sphere of crystal the artist had made “to get the lights and colors right,” because actual bubbles were too momentary to paint. The bubbles themselves echo back to the tradition of the “vanitas painting,” symbolic of the fragility and fleeing nature of human existence (think, for example, of Chardin’s Soap Bubbles). And the association of the bubbles with the young boy remained so ingrained that young Willie, who as an adult rose to be an admiral in the Royal Navy, was called “Bubbles” for the rest of his life.

Did Millais sell out?

By the time this was painted in 1886, Millais was one of the most prominent artists of the Victorian age. Bubbles, which was originally going to be titled A Child’s World, is typical of many of Millais’s paintings of the period and exemplifies the reasons for his popularity with the Victorian audience. His many pictures of beautiful children, in both contemporary and historical dress, masterfully capture the innocence of childhood. Millais’s artistic virtuosity is evident, and combined with the wistful nature of the subjects, the artist’s paintings were calculated to pull at Victorian heartstrings. It is no wonder that Millais was a financially successful and sought after painter.

A few years before, Millais’s painting of a charming girl in an 18th-century costume, Cherry Ripe, had taken the Victorian art world by storm. The painting sold for £1,000 to the editor of the art journal The Graphic, William Luson Thomas. In December 1880 the magazine offered prints of the painting made by engraver Samuel Cousins, selling at least 500,000, with an estimated additional 500,000 people unable to obtain a copy. The incredible popularity of the image meant that according to J. G. Millais, “Thanks to the engraver’s and woodcutter’s art, Cherry Ripe found its way into the remotest parts of the English-speaking world, and everywhere that sweet presentment of English Childhood won the hearts of the people. From Australian miners, Canadian backwoodsmen, South African treckers, . . . came to the artist letters of the warmest congratulation.” [2] For an artist with a wife and eight children to support, this popular and financial success must have been welcome.

J. G. Millais explained that Bubbles was purchased for The Illustrated London News by Sir William Ingram, and the artist expected it to be reproduced in a similarly commercial manner as Cherry Ripe. Copyright to the image was also ceded to Ingram. In 1887 the painting (along with the copyright) was sold to the Thomas Barratt, managing director of Pears Soap. Known as “the father of modern advertising” Barratt added the company logo to the picture and began using the image to advertise its signature product.

Proof of advertisement for Pears Soap, adapted from a painting by Sir John Everett Millais, Bubbles, c. 1888 or 1889, color lithograph, 16.5 x 11.6 cm (V&A)

According to J. G. Milllais, at first the artist was “furious,” but ultimately “admitted that the work was admirably done,” but expressed “his regret at the purpose to which it was to be turned.” The younger Millais also offers his opinion that “the example they set has tended to raise the character of our illustrated advertisements, whether in papers or posters, and may possibly lead to the final extinction of such atrocious vulgarities as now offend the eye at every turn.” [3] Others were not so forgiving and a spirited debate over “high art” in such a pedestrian use as advertising continued. The novelist Marie Corelli included a reference to this in her 1895 The Sorrows of Satan when one of the characters laments “the fame of Millais as an artist was marred when he degraded himself to the level of painting the little green boy blowing bubbles of Pears Soap.” [4] After discussion with the artist, Corelli removed the offending phrase from later editions of the novel, but the sentiment of the time was clear. Millais was stepping into new artistic territory.

A famous artist

In his own lifetime, Millais’ fame as an artist far outshone that of his early Pre-Raphaelite comrades. Millais’ election as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1853 was, according to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the end of the PRB. One wonders what Rossetti (who died in 1882) would have thought of a painting like Bubbles or Millais’ election as President of the Royal Academy in 1896, although he was only to serve for 6 months before his death at age 67. Of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, John Everett Millais was the one to stray farthest from the original ideals of the brotherhood. Much of his later work, which mainly consisted of portraits, child subjects, and moody landscapes is far different from his earlier Pre-Raphaelite choices of medieval and literary subjects and historical star-crossed lovers. His handling of the paint itself also changes, becoming more fluid and far less detailed. These changes moved him away from his early Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, however, in doing so he became one of the greatest artists of the Victorian period.