Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884-86, oil on canvas, 207.5 x 308.1 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

Just a dozen years after the debut of Impressionism, the art critic Félix Fénéon christened Georges Seurat as the leader of a new group of “Neo-Impressionists.” He did not mean to suggest the revival of a defunct style — Impressionism was still going strong in the mid-1880s — but rather a significant modification of Impressionist techniques that demanded a new label.

Fénéon identified greater scientific rigor as the key difference between Neo-Impressionism and its predecessor. Where the Impressionists were “arbitrary” in their techniques, the Neo-Impressionists had developed a “conscious and scientific” method through a careful study of contemporary color theorists such as Michel Chevreul and Ogden Rood. [1]

A scientific method

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette, 1876, oil on canvas, 131 x 175 cm (Musée d’Orsay)

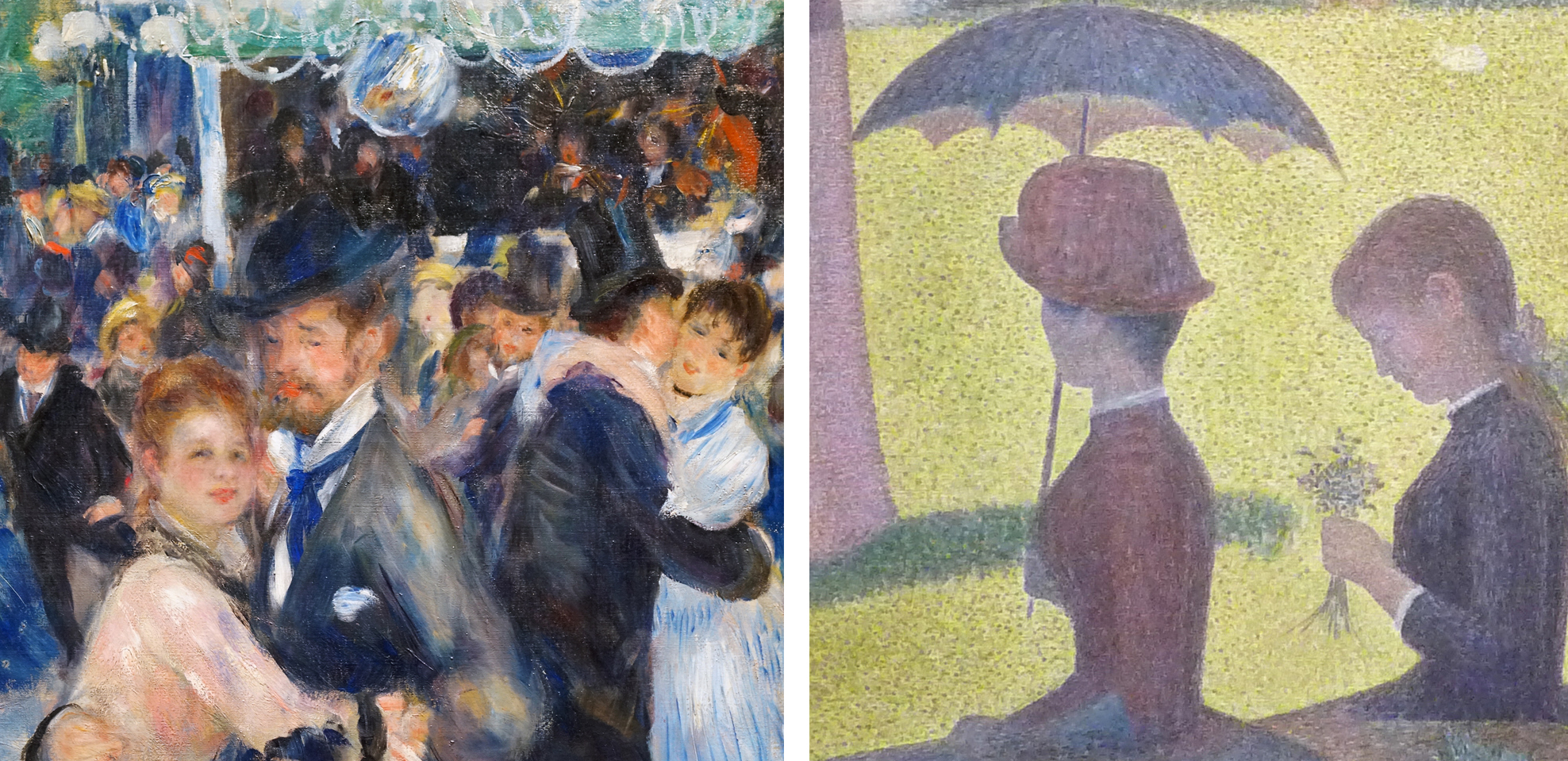

This greater scientific rigor is immediately visible if we compare Seurat’s Neo-Impressionist Grande Jatte with Renoir’s Impressionist Moulin de la Galette. The subject matter is similar: an outdoor scene of people at leisure, lounging in a park by a river or dancing and drinking on a café terrace. The overall goal is similar as well. Both artists are trying to capture the effect of dappled light on a sunny afternoon. However, Renoir’s scene appears to have been composed and painted spontaneously, with the figures captured in mid-gesture. Renoir’s loose, painterly technique reinforces this effect, giving the impression that the scene was painted quickly, before the light changed.

Left: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette, detail, 1876, oil on canvas, 131 x 175 cm (Musée d’Orsay); Right: Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, detail, 1884-86, oil on canvas, 207.5 x 308.1 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

By contrast, the figures in La Grande Jatte are preternaturally still, and the brushwork has also been systematized into a painstaking mosaic of tiny dots and dashes, unlike Renoir’s haphazard strokes and smears. Neo-Impressionist painters employed rules and a method, unlike the Impressionists, who tended to rely on “instinct and the inspiration of the moment.” [2]

Pointillism and optical mixture

One of these rules was to use only the “pure” colors of the spectrum: violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. These colors could be mixed only with white or with a color adjacent on the color wheel (called “analogous colors”), for example to make lighter, yellower greens or darker, redder violets. Above all, the Neo-Impressionists would not mix colors opposite on the color wheel (“complementary colors”), because doing so results in muddy browns and dull grays.

More subtle color variations were produced by “optical mixture” rather than mixing paint on the palette. For example, examine the grass in the sun. Seurat intersperses the overall field of yellow greens with flecks of warm cream, olive greens, and yellow ochre (actually discolored chrome yellow). Viewed from a distance these flecks blend together to help lighten and warm the green, as we would expect when grass is struck by the yellow-orange light of the afternoon sun. It was this technique of painting in tiny dots (“points” in French) that gave Neo-Impressionism the popular nickname”Pointillism” although the artists generally avoided that term since it suggested a stylistic gimmick.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, detail, 1884-86, oil on canvas, 207.5 x 308.1 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

For the grass in the shadows, Seurat uses darker greens intermixed with flecks of pure blue and even some orange and maroon. These are very unexpected colors for grass, but when we stand back the colors blend optically, resulting in a cooler, darker, and duller green in the shadows. This green is, however, more vibrant than if Seurat had mixed those colors on the palette and applied them in a uniform swath.

Similarly, look at the number of colors that make up the little girl’s legs! They include not only the expected pinks and oranges of Caucasian flesh, but also creams, blues, maroons, and even greens. Stand back again, though, and “optical mixture” blends them into a convincing and luminous flesh color, modeled in warm light and shaded by her white dress. (For more technical information on this topic, see Neo-Impressionist color theory).

Compositional rigor

Georges Seurat, Study for A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884, oil on canvas, 70.5 x 104.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Neo-Impressionists also applied scientific rigor to composition and design. Seurat’s friend and fellow painter Paul Signac asserted,

The Neo-Impressionist … will not begin a canvas before he has determined the layout … Guided by tradition and science, he will … adopt the lines (directions and angles), the chiaroscuro (tones), [and] the colors (tints) to the expression he wishes to make dominant. Paul Signac, Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, in Nochlin, ed., p. 121.

Numerous studies for La Grande Jatte testify to how carefully Seurat decided on each figure’s pose and arranged them to create a rhythmic recession into the background. This practice is very different from the Impressionists, who emphasized momentary views (impressions) by creating intentionally haphazard-seeming compositions, such as Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette.

Georges Seurat, Parade de cirque, 1887-88, oil on canvas, 99.7 x 149.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Seurat’s Parade de cirque is even more rigorously geometrical. It is dominated by horizontal and vertical lines, and the just slightly off-rhythmic spacing of the figures and architectural structure creates a syncopated grid. Scholars have debated whether the composition is based on the Golden Section, a geometric ratio that was identified by ancient Greek mathematicians as being inherently harmonious.

Systematized expression

The Neo-Impressionists also attempted to systematize the emotional qualities conveyed by their paintings. Seurat defined three main expressive tools at the painter’s disposal: color (the hues of the spectrum, from warm to cool), tone (the value of those colors, from light to dark), and line (horizontal, vertical, ascending, or descending). Each has a specific emotional effect:

Gaiety of tone is given by the dominance of light; of color, by the dominance of warmth; of line, by lines above the horizontal. Calmness of tone is given by an equivalence of light and dark; of color by an equivalence of warm and cold; and of line, by horizontals. Sadness of tone is given by the dominance of dark; of color, by the dominance of cold colors; and of line, by downward directions. Georges Seurat, Letter to Maurice Beaubourg, August 28, 1890, in Nochlin, ed., p. 114 (translation modified for clarity).

Seurat’s Chahut (Can-Can) seems designed to exemplify these rules, employing mostly warm, light colors and ascending lines to convey a mood of gaiety appropriate to the dance.

The Neo-Impressionist style had a relatively brief heyday; very few artists carried on the project into the 20th century. However, a great many artists experimented with it and took portions of its method into their own practice, from van Gogh to Henri Matisse. More broadly, the Neo-Impressionist desire to conform art-making to universal laws of perception, color, and expression echoes throughout Modernism, in movements as diverse as Symbolism, Purism, De Stijl, and the Bauhaus.

So far we have concentrated on the style of Neo-Impressionism. In Part 2, we will examine the subject matter favored by the artists, and discuss its relation to the social and political context of the late-nineteenth century.

Notes:

- Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes en 1886,” as translated in Linda Nochlin, ed., Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874-1904: Sources and Documents (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), p. 108.

- Paul Signac, From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899), as translated in Nochlin, ed., p. 122.