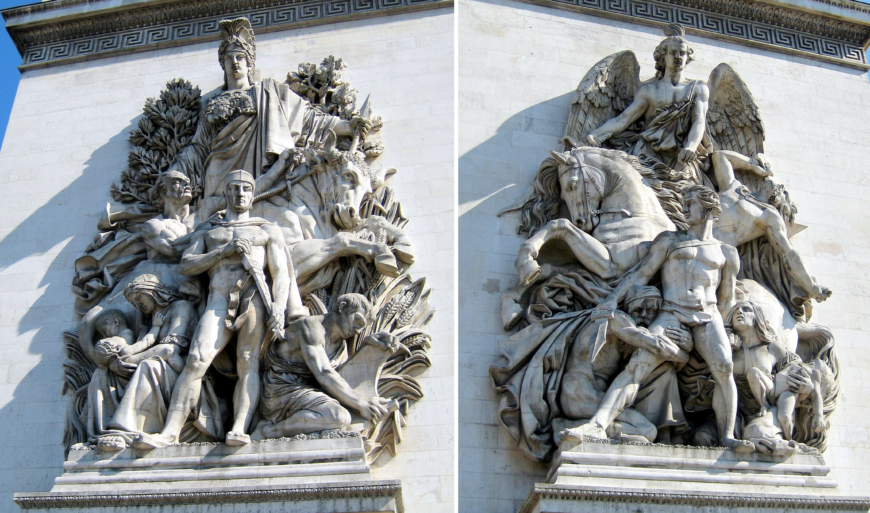

François Rude, La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792), 1833–6, limestone, c. 12.8 m high, Arc de Triomphe de l’Etoile, Paris (photo: Storm Crypt, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Rude before The Departure

François Rude had revolution in his blood. At eight years-old, he watched his father, a stovemaker, join the volunteer army to defend the new French Republic (this is shortly after the French Revolution) from the threat of foreign invasion. Fiercely loyal himself, as a young man he was a Bonapartist (a follower of the emperor Napoleon Bonaparte). His support for the Emperor during the Cent Jours of 1814, when Napoleon returned to France from exile and tried to seize power from the newly restored monarch Louis XVIII, meant that Rude was forced to leave the country when Napoleon was finally defeated in 1815. Like the painter David, another ardent Bonapartist, he lived for some years in Belgium, returning to his native country in 1827.

François Rude, Neapolitan Fisherboy, 1831–3, Marble, 77.5 cm high (Louvre, Paris)

His reputation grew over the next ten years, reaching its peak with the justly famous La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792) (above). Rude was awarded the commission on the strength of his hugely popular work, Neapolitan Fisherboy, a disarmingly cheerful and down-to-earth nude figure which was exhibited in plaster in the Salon of 1831. The sculpture seemed to conjure up the carefree lifestyles of humble Italian folk; a complete fiction, of course, but a dose of escapism was just what the French felt they needed following the turmoil of the July Revolution of 1830. An early, if somewhat toothless example of Romantic sculpture, it was bought by the state and for his efforts Rude was awarded the cross of the Legion of Honour.

The Arc de Triomphe

The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792, also known as La Marseillaise, is a different work entirely, more in keeping with what one now thinks of as Romantic; like a Beethoven symphony: intense, rousing, full of drama and movement.

Jean Chalgrin, Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, 1806–36, 50 x 45 x 22 m, Paris (photo: Alfvanbeem, CC0 1.0)

It is Rude’s masterpiece and one of the best-known sculptures in the world. Its location has obviously contributed to its fame, attached as a bas-relief to the right foot of the façade of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris—on the Champs-Elysées facing side. An enormous fifty meters high structure, designed to celebrate France’s military achievements in 1806 by Jean Chalgrin, the arch’s construction was begun under Napoleon’s orders but remained unfinished when finally he was defeated in 1815.

Jean-Pierre Cortot, The Apotheosis of Napoleon I (The Triumph of 1810), 1833–1836, limestone, Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, Paris (photo: falling_angel, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The project was picked up again during the Constitutional Monarchy of Louis-Philippe (1830–48). The arch’s sculptural programme, seen by the king and his ministers as an ideal opportunity to promote national reconciliation, aimed to offer something that would please every segment of the French political spectrum. If Rude’s work flattered the Republicans (those who wanted to create a Republic in France), to the left of it, Cortot’s The Apotheosis of Napoleon I, or The Triumph of 1810 was pitched to the Bonapartists.

On the opposite side of the arch is Antoine Étex’s war and peace pendant group, The Resistance of 1814 and Peace—the former a stirring image of Napoleon’s supporters who continued to fight after his return from exile, the latter, appealing to the monarchists, an allegorical depiction of the Treaty of Paris that saw the restoration of the Bourbon royal dynasty.

Left: Antoine Étex, Peace, 1833–36, Limestone, Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, Paris; Right: Antoine Étex, The Resistance, 1833–36, Limestone, Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, Paris (photos: Wally Gobetz, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

When the arch was officially unveiled in 1836, there was unanimous agreement that Rude’s group made the other three pale into insignificance.

The sculpture and the song

The subject of Rude’s La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792) commemorates the Battle of Valmy when the French defended the Republic against an attack from the Austro-Prussian army. The popular title for the work, La Marseillaise, is the name of the French national anthem, which was written in 1792 by the army officer Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle as part of a recruitment campaign. It was sung by a young volunteer, later to become a general under Napoleon, at a patriotic gathering in Marseille, the city from which the song gets its name, and was subsequently adopted as the army’s rallying cry.

Genius of Liberty (detail), François Rude, La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792), 1833–6, limestone, c. 12.8 m high, Arc de Triomphe de l’Etoile, Paris (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Banned under the Bourbon administration, it was sounded by the crowds on the barricades in the July Revolution of 1830 and in the following years grew in popularity, the Romantic composer Hector Berlioz, for instance, giving it an orchestral arrangement. Having lodged itself so deeply in the public consciousness, evoking the spirit of republican defiance in the face of tyranny, the song must surely have been in Rude’s mind when drawing his designs for the sculpture.

The surge of the volunteers, inspired by the great sweeping movement of the Genius of Liberty above them, effectively illustrates in limestone the penultimate verse of the song:

Sacred love of the Fatherland,

Lead, support our avenging arms

Liberty, cherished Liberty,

Fight with thy defenders!

Under our flags, shall victory

Hurry to thy manly accents,

See thy triumph and our glory!

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (July 28, 1830), September–December 1830, oil on canvas, 260 x 325 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace, Lartos marble (ship) and Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E. 3.28m high (Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Like other great works of the period, Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, for instance, Rude’s sculpture effectively captures the energy of the new republic, more so perhaps than anything to be found in the art of the 1792 generation. It was their children, it seems, imbued with tales of heroic sacrifice, who, employing this epic, revolutionary style, known as Romanticism, brought to light the passion and the glory and, in the case of Delacroix, the hideous spectacle of death, too, that went into forging the new France.

This is not to say that Rude rejected neoclassicism, the treatment of the figures, some nude, some dressed in classic armor, draws heavily from antiquity, while the allegorical figure of Liberty recalls the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre.

The composition

Also, in the composition Rude uses the classical device of bilateral symmetry, positioning the figures along two axes: a horizontal axis that divides the frieze of soldiers in the lower half from the winged figure that fills the upper register; and a vertical axis that runs from the head of the Genius of Liberty through the vertical juncture between the two central soldiers. One suspects, in its vortex-like structure, Rude had studied in some detail Rubens’s copy of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari in the Louvre.

Peter Paul Rubens, Copy after Leonardo’s ‘Battle of Anghiari,’ c. 1604, black chalk, pen and ink, highlights in grey and white, 45.2 x 63.7cm (Louvre, Paris)

As with Leonardo, forms overlap, notably in the bottom register in which we find the head of a horse and two other soldiers positioned behind the five frontal figures, strengthening the group as a whole, which, when viewed from below, forms a semi-circular mass, packed tightly onto the plinth, at the point of spilling off it. Unlike Leonardo’s Battle, however, whose composition spirals inwards to a point of internal collapse, in The Departure, the bodies move like a wave, cresting at the point where the bearded soldier’s head overlaps with the leg of the Genius of Liberty, as though inspired by her to rally his troops to victory.

Mixed messages

For Rude and his fellow republicans, this was stirring stuff. As it happened, it was also the cause of celebration for the present government. The king, Louis-Philippe, was an Orleans, a member of that branch of the French royal family that, though related to the Bourbons, had been treated as subordinates by them.

For this reason, as a young man, he had shown support for the Revolution, even taking up arms in the Battle of Valmy, where he commanded his own division and exhibited some bravery. The Departure is therefore in its way a curious and rather paradoxical piece of propaganda, for in eulogizing the Revolutionary army who fought against the threat of an invasion that sought to restore the monarchy, the work also helps to lend credibility to Louis-Philippe, the ruling monarch.

This contradictory state of affairs would not have been lost on Rude who, despite the acclaim won by The Departure, over the coming years found himself more and more in opposition to the regime, nor for that matter was it lost on the French people themselves who having once and for all grown tired of monarchs, forced the abdication of their last one, Louis-Philippe, in the Revolution of 1848. Rude’s great call for the Liberty and the Republic, it would seem, was the one that triumphed in the end.

Additional resources:

François Rude’s Neopolitan Fisherboy at the Louvre

Listen to the La Marseillaise, the French national anthem

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”RudeArc,”]