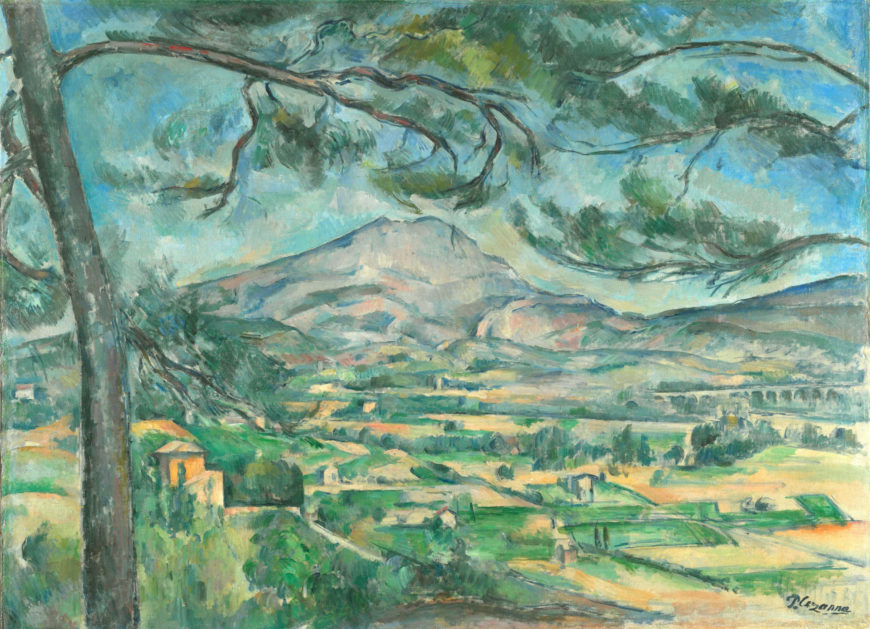

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902–04, oil on canvas, 73 x 91.9 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:06] Paul Cézanne is probably best known for two things: his still lifes with apples and his landscapes of a mountain in the south of France in Provence known as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:16] We’re looking at a painting of Mont Sainte-Victoire here in the Philadelphia Museum of Art that dates to 1902-04. It’s interesting to think about Cézanne painting this mountain over and over again, but also painting each painting of the mountain over an extended period of time. Normally, we think about Impressionism as paintings that are done on site rather rapidly. This is decidedly different.

Dr. Zucker: [0:39] Paul Cézanne is often grouped with Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Seurat and called a Post-Impressionist, but he began his career exhibiting with the Impressionists in Paris. He moved back to the area that he grew up in in the south of France later in his life. This painting was made in the last few years of his life. He would die just two years after it was completed.

Dr. Harris: [0:58] It’s funny to talk about this painting being completed because it feels unfinished. There are places where we see the canvas underneath. There are buildings that seem to be taking shape. There are trees that seem to be half-formed. Even the mountain itself seems to be almost in the process of forming.

Dr. Zucker: [1:17] We can clearly read a mountain, a sky, clouds, trees, farmland, and buildings. At the same time, if we look too closely, they all fall apart. They are all formed [of] a series of hash marks that create a sense of optical movement and change. Think about historically what it means for an artist to do this with landscape.

[1:36] From the 17th century forward, painters like Poussin or Claude had been deeply concerned with creating space that was believable. Cézanne seems to be here directly attacking that tradition. He’s creating what has been referred to as “a curtain of paint.”

[1:50] The paint is so present throughout the surface of the canvas — in the sky, in the foreground — that all of it rises up to the surface. All of it announces its two-dimensionality, that it is on a vertical plane.

Dr. Harris: [2:03] The whole tradition of landscape painting, and even the academic tradition in France of painting, generally, is about high finish, not seeing the brushstrokes, which are so emphatically present here.

[2:15] To me, I’m not sure that he’s attacking that tradition so much as being true to his own personal vision as he stood in front of this landscape. Here he is, the end of the 19th century, the early years of the 20th century, Impressionism has happened, this idea of depicting your own sensations or subjective optical experience in front of the landscape. I think that’s a big part of this for him.

Dr. Zucker: [2:40] There is an intimacy of vision, of a man that has spent a lifetime looking at this mountain from these vantage points and is understanding his own visual experience and inventing a visual language to portray that experience.

Dr. Harris: [2:53] Cézanne will be important for Cubism. If we think about a painting like Braque’s “Viaduct at L’Estaque”, you can see how Braque is thinking about the forms in terms of geometric shapes. We have some sense of that here.

Dr. Zucker: [3:08] Where Braque and Picasso will fully open up form, what we have here is Cézanne just beginning to investigate what it means to break contour. Look, for example, at the houses in the foreground. We can see the way in which the color of the field enters into the area that should be just the red of the roof.

[3:25] It’s just a subtle opening up of form, ever so slightly, whereas Braque and and Picasso will dismantle form almost completely.

Dr. Harris: [3:32] From the hindsight of the 20th century, we see this as an affirmation of the flatness of the canvas, a denying of the illusionism that was such an important part of Western painting beginning in the Renaissance.

Dr. Zucker: [3:45] We shouldn’t say complete denial because we can still see the mountain in the background. We can still see the foreground of the hills before. We can still see the brush immediately below our feet as we look from an adjacent hilltop. Nevertheless, all the subtle cues that had built up in landscape painting in the centuries before have been left out.

Dr. Harris: [4:04] Normally, we would expect to see atmospheric perspective. We would expect to see the sky and mountains in the distance fading and becoming less bright in color, less clear in their focus, but in that way, Cézanne is treating every part of this canvas in the same way.

Dr. Zucker: [4:21] Instead of using atmospheric perspective to create a sense of form, the artist is simply delineating distance by choice of color. We have these blue-browns in the foreground. We have reds and greens in the middle ground, and we have blues in the most distant area. It is a kind of arbitrary association of place with color.

[4:39] Cézanne is able to create an even greater degree of ambiguity by bringing color from one realm into the other. Look, for instance, at the way that Cézanne takes that gray-purple from the immediate foreground and builds that into the sky, so that when we see those colors in relationship to each other, that sky comes forward.

Dr. Harris: [4:54] What we have here is an investigation of landscape that’s very different than what the Impressionists were doing. This is not about capturing the transitory effect of light in the atmosphere. This seems to be about something more permanent.

Dr. Zucker: [5:07] What Cézanne is after, it seems to me, is a tension between the deep recession that we expect and a radical confrontation with the two-dimensionality of the surface.

[5:16] [music]

It can be difficult to estimate, by eye, just how far away a mountain lies. A peak can dominate a landscape and command our attention, filling our eyes and mind. Yet it can come as something of a shock to discover that such a prominent natural feature can still be a long distance from us.

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902–04, oil on canvas, 73 x 91.9 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A mountain

At 3317 feet (1011 meters) high, the limestone peak of Mont Sainte-Victoire is a pigmy compared to the giants of, say, Mount Fuji and Mount Rainier. But, like them, it still exercises a commanding presence over the country around it and, in particular, over Aix-en-Provence, the hometown of Paul Cézanne. Thanks to his many oil paintings and watercolors of the mountain, the painter has become indelibly associated with it. Think of Cézanne and his still-lifes and landscapes come to mind, his apples and his depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Paul Cézanne, Bathers at Rest, 1876–77, oil on canvas, 82 x 101 cm (The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia)

Steeped in centuries of history and folklore, both classical and Christian, the mountain—or, more accurately, mountain range—only gradually emerged as a major theme in Cézanne’s work. In the 1870s, he included it in a landscape called The Railway Cutting, 1870 (Neue Pinakothek, Munich) and a few years later it appeared behind the monumental figures of his Bathers at Rest, 1876–77 (The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia), which was included in the Third Impressionist Exhibition of 1877. But it wasn’t until the beginning of the next decade, well after his adoption of Impressionism, that he began consistently featuring the mountain in his landscapes. Writing in 1885, Paul Gauguin was probably thinking of Mont Sainte-Victoire when he imagined Cézanne spending “entire days in the mountains reading Virgil and looking at the sky.” “Therefore,” Gauguin continued, “his horizons are high, his blues very intense, and the red in his work has an astounding vibrancy.” Cézanne’s legend was beginning to emerge and a mountain ran through it.

A series

Cézanne would return to the motif of Mont Sainte-Victoire throughout the rest of his career, resulting in an incredibly varied series of works. They show the mountain from many different points of view and often in relationship to a constantly changing cast of other elements (foreground trees and bushes, buildings and bridges, fields and quarries). From this series we can extract a subgroup of over two-dozen paintings and watercolors. Dating from the very last years of the artist’s life, these landscapes feature a heightened lyricism and, more prosaically, a consistent viewpoint. They show the mountain as it can be seen from the hill of Les Lauves, located just to the north of Aix.

Mont Sainte-Victoire (photo: Bob Leckridge, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A walk from the studio

Cézanne bought an acre of land on this hill in 1901 and by the end of the following year he had built a studio on it. From here, he would walk further uphill to a spot that offered a sweeping view of Mont Sainte-Victoire and the land before it. The painter Emile Bernard recalled accompanying Cézanne on this very walk:

Cézanne picked up a box in the hall [of his studio] and took me to his motif. It was two kilometers away with a view over a valley at the foot of Sainte-Victoire, the craggy mountain which he never ceased to paint[…]. He was filled with admiration for this mountain.

Cézanne consciously cultivated his association with the mountain and perhaps even wanted to be documented painting it. When they visited Aix in 1906, the artists Maurice Denis and Ker-Xavier Roussel found themselves being led to the same location. In an oil painting by Denis and in some of Roussel’s photographs, we see Cézanne standing before his easel and painting the mountain. Again! It was the view we can see in most of Cézanne’s late views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, including the painting that concerns us here, which is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The painting in Philadelphia

In this work, Cézanne divides his composition into three roughly equal horizontal sections, which extend across the three-foot wide canvas. Our viewpoint is elevated. Closest to us lies a band of foliage and houses; next, rough patches of yellow ochre, emerald, and viridian green suggest the patchwork of an expansive plain and extend the foreground’s color scheme into the middleground; and above, in contrasting blues, violets and greys, we see the “craggy mountain” surrounded by sky. The blues seen in this section also accent the rest of the work while, conversely, touches of green enliven the sky and mountain.

Detail, Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902–04, oil on canvas, 73 x 91.9 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Subtle adjustments

In other words, Cézanne introduced subtle adjustments in order to avoid too simple a scheme. So the peak of the mountain is pushed just to the right of center, and the horizon line inclines gently upwards from left to right. In fact, a complicated counterpoint of diagonals can be found in each of the work’s bands, in the roofs of the houses, in the lines of the mountain, and in the arrangement of the patches in the plain, which connect foreground to background and lead the eye back.

Flatness and depth

Cézanne evokes a deep, panoramic scene and the atmosphere that fills and unifies this space. But it is absolutely characteristic of his art that we also remain acutely aware of the painting as a fairly rough, if deftly, worked surface. Flatness coexists with depth and we find ourselves caught between these two poles—now more aware of one, now the other. The mountainous landscape is both within our reach, yet far away.

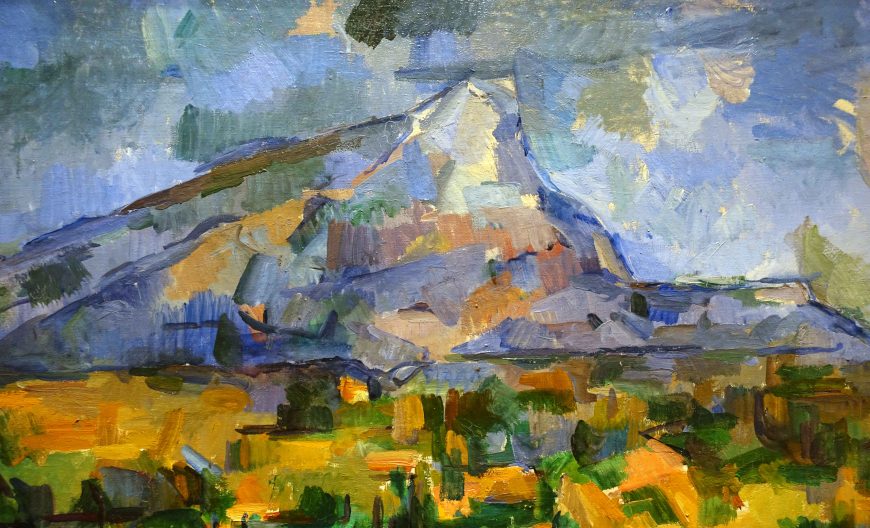

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, c. 1887, oil on canvas, 66.8 x 92.3 cm (The Courtauld Gallery, London)

A comparison

Comparing the Philadelphia canvas with some of Cézanne’s other views of Mont Sainte-Victoire and with photos of the area can help us to grasp some of the perceptual subtleties and challenges of the work. Take the left side of the mountain. Though the outermost contour is immediately apparent, inside of it one can also discern a second line (or, more accurately, a series of lines and edges). The two converge just shy of the mountaintop. The area between this outer contour and the interior line or ridge demarcates a distinctive spatial plane; this slope recedes away from us and connects to the larger mountain range lying behind the sheer face. Attend to this area, and the mountain seems to gain volume. It becomes less of an irregular triangle and more of a complicated pyramid.

Detail, Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902–04, oil on canvas, 73 x 91.9 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Or look again at the painting’s most obvious focus of interest, the top of the mountain. Cézanne’s other works show that the mountain has a kind of double peak, with a slightly higher point to the left side and a lower one to the right. At first glance, the Philadelphia canvas seems to contradict this: the mountain’s truncated apex appears to rise slightly from left to right. But a closer look reveals that Cézanne does respect topography. The small triangular patch of light gray—actually the priming of the canvas—can be read as belonging to the space immediately above the mountain or perhaps as a cloud behind it. Thus it is the gray and light blue brushstrokes immediately below this patch that describe the downward slant of the mountain top.

Curiously, in one respect, our point-of-view is actually a little misleading. At an elevation of 3104 feet (946 meters), the left peak is not the highest point, but merely appears to so from Les Lauves. A huge iron cross—la croix de Provence—was erected on this spot in the early 1870s, the fourth to be placed there. Though visible from afar, the cross appears in none of Cézanne’s depictions of the mountain.

Cézanne had presumably stood on this summit, or these summits, several times. He had thoroughly explored the countryside around Aix, first during youthful rambles with his friends and later as a plein-air artist in search of motifs. And we know for certain that he had climbed to the top of the mountain as recently as 1895. Armed with these experiences, he could have estimated the distance from Les Lauves to the top of Mont Sainte-Victoire with some accuracy—it’s about ten miles (16 kilometers) as the crow flies.

Detail, Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902–04, oil on canvas, 73 x 91.9 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When he stood on the mountain in 1895 Cézanne had, so to speak, entered into one of his own landscapes. As he stood there, perhaps he paused to recall some of the paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire he had already made. But, to return to Gauguin’s language, could he possibly have dreamt of the works he would go on to paint in the following decade—works like the Philadelphia landscape, with its high horizon, intense blues, and astounding vibrancy?