Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

From Gogol to Google

If you’re a fan of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, or Gogol, then chances are you’ve probably seen a painting, or at least a detail of a painting, by Ilya Repin, the most celebrated Russian artist of the nineteenth century. Unlike his great literary contemporaries, Repin is not a household name in the English-speaking world, his work perhaps best known to us through the covers of our Penguin Classics. Things are changing though. Major exhibitions and publications have been bringing Repin and Russian visual art of the nineteenth century to our attention. Now, with rooms from the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow uploaded onto the Google Art Project, we can examine in remarkable detail, some of the greatest examples of 19th century Russian Realism.

Ilya Repin

Repin’s work is often mentioned in connection with the Wanderers (Peredvizhniki, in Russian), a band of artists who exhibited their work, all distinctively Russian in character, across the country. Repin, however, only joined the movement in 1878, eight years after its founding, when his reputation as one of the leading artists of his generation was firmly established.

The most probable reason for this delay was Repin’s deep-seated anxiety about poverty. Born in penury to a peasant family in the Ukraine, at twelve he became an apprentice of a local icon painter. Later he went to the Imperial Academy at Saint Petersburg. The formal completion of his studies required that he find sponsorship to finance himself or else be forced into an impoverished life of a unqualified artist, who, working for his landowner, would be little better off than a bonded laborer. Desperate to avoid this fate, Repin eventually found a wealthy St. Petersburg general to sponsor him. He fell to his knees and kissed the hem of the man’s dressing gown. As he stood up he noticed that he had never seen hands so smooth and soft, just the sort of person, in fact, that later in life he would refuse to paint for, declaring: ‘The peasant is the judge now and we must reproduce his interests.”

Shrine carried in procession (detail), Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

Pious women carrying empty box (detail), Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

The procession

Depicted is a panoramic view of a religious procession carrying the icon of Our Lady of Kursk in a gilded shrine. Behind the shrine two women with somber downcast faces carry the empty box, which would normally house the shrine. Their pious humility contrasts with the bloated and lumbering figures of the landowner and his wife who holds a shimmering golden icon.

Priest in gold vestments (detail), Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

The irony is apparent in the anything-but-holy looking figure of the priest, dressed in golden vestments, running a hand through his yellow hair. He alone engages with the viewer drawing attention our to the vanity of the proceedings.

To the left the mounted Cossack militia and priest stewards that preside over the procession, separate the poorest of the poor from the main body, one raises his whip in a menacing gesture. They are headed by a hunchbacked boy, the most positive figure in the painting.

He moves resolutely forward, while a man, perhaps his father, cruelly compels him on, his whip casting a shadow in the sand that divides the boy from the religious icon. What motivates him seems to otherwise than the gaudy display of vanities.

Hunchbacked boy at the front of the impoverished in procession (detail), Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

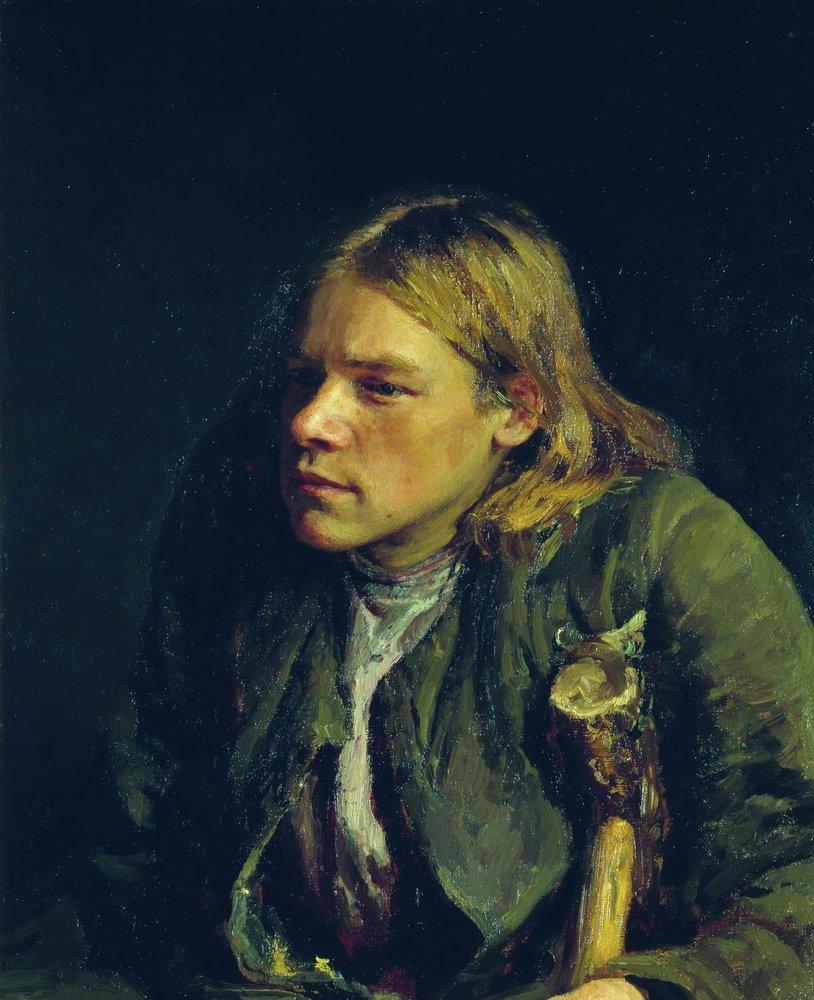

Unlike that other peasant artist, Millet, Repin takes pains to paint individual portraits of the people in the procession. Nowhere is this is more beautifully achieved than in the figure of the hunchback, for which several preparatory sketches exist, including a finely worked oil painting. The young man is shown as sensitive, dignified and without sentimentality. In the last half of the nineteenth century, peasants were frequently sentimentalized, but Repin clearly disdained this trend, which he found to his annoyance in the writings of the elderly Tolstoy. Speaking of the peasant, Repin wrote, “To descend for one minute into this darkness and to say ‘I am with you,’ is hypocrisy. To wallow with them forever is a senseless sacrifice. To elevate them! To elevate them to one’s own level, to give life—this is a heroic deed!’”

Mad Russia

Repin began his first version of the procession in 1876, shortly after his return from a three-year stay in France and Italy. Perhaps these experiences of other cultures sharpened his sense of the injustice in his own. The choice of subject was certainly rooted in a profound sense of personal hurt: “I am applying all my insignificant forces to try to give incarnation to my ideas; life around me disturbs me a great deal and gives me no peace—it begs to be captured on canvas,” he wrote.

Crowd propelled by authority (detail), Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk Gubernia, 1880–83, oil on canvas, 175 x 280 cm (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

By 1883 the subject had developed into a harsh record of contemporary life, incorporating various strata of Russian society. Though following a shared path, the crowd seems propelled by a heartless authority. The mounted police and the clergy who glower over the poor or stare out oblivious to their suffering, are presented as bullying and vainglorious.

Memories of Repin’s own childhood shaped the composition. As a young icon painter he would have regularly handled objects that inspired veneration in the hearts of the faithful and he would have witnessed many religious processions in the village where he grew up. Nevertheless, this is not a religious painting. Rather than creating an image of exultation, Repin is more concerned with the psychology of the individual and of the crowd itself, influenced no doubt by the crowd scenes of Courbet and Manet, too, whose work he greatly admired.

The complex social caste system of rural Russia is a world away from that of Courbet’s Ornans or Manet’s Paris though. Aside from the church, the state and the military, the average peasant was also liable to be oppressed within his own social ranks, the peasant class being divided into several subsections: those that could read and those that could not, those that had livestock and those with none, and so on, and so forth. Repin masterfully delineates these tensions within the painting.

Reception

The painting was purchased by Pavel Mikhaylovich Tretyakov, a textile magnate, who suggested changing the maids carrying the icon to “a beautiful young girl, exuding spiritual rapture”; a suggestion Repin did not follow up.

Some criticized the painting on the grounds of its depiction of drunkenness at a religious procession. Another, more nuanced criticism came from the artist Mikhail Vrubel who challenged Repin’s desire to “let the peasant be the judge now.” For Vrubel, it is the artist who should define taste, not the audience, accusing Repin of debasing art “to the level of a public statement.”

Vrubel’s criticism has held firm, reflecting the importance of modernism in defining twentieth century tastes. Stalin held Repin up as the master of Russian socialist art, a commendation that perhaps understandably has, for some art historians, placed him in conflict with the avant-garde. This, however, is to underplay Repin’s radical painterly style as well as the importance of the social message of his painting, a message that took great courage and even a greater sense of humanity to create.