Monet paints the surface of the water itself, refusing the viewer the anchoring presence of a horizon or shoreline.

Claude Monet, Les Nymphéas (The Water Lilies), suite of paintings on permanent exhibition at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. Room 1: Morning, oil on two canvas panels, 200 x 425 cm, c. 1918–26 Clouds, oil on three canvas panels, 200 x 1275 cm, c. 1918–26 Green Highlights, oil on two canvas panels, 200 x 850 cm, c. 1918–26 Sunset, oil on canvas, 200 x 600 cm, c. 1918–26 Room 2: Reflection of Trees, oil on two canvas panels, 200 x 850 cm, c. 1918–26 The Morning Light, the Willows, oil on three canvas panels, 200 x 1275 cm, c. 1918–26 The Morning Willows, oil on three canvas panels, 200 x 1275 cm, c. 1918–26 The Two Willows, oil on four canvas panels, 200 x 1700 cm, c. 1918–26

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the l’Orangerie in Paris, and we’re looking at one of Monet’s Water Lily rooms.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:11] It’s in an oval shape, lit from above.

Dr. Zucker: [0:14] Through a scrim, which gives it a really lovely, soft light. There is this sense that these are contemplative works, which ties them in an interesting way to a kind of solemnity of the sort that you would expect in a religious context.

Dr. Harris: [0:25] Oh, no doubt. This is painted late in Monet’s life, after the death of his wife and after the death of his son, so I think there is a sense for him of his legacy.

Dr. Zucker: [0:36] He gave them to the French state, and the state in turn decided to build this pavilion for them.

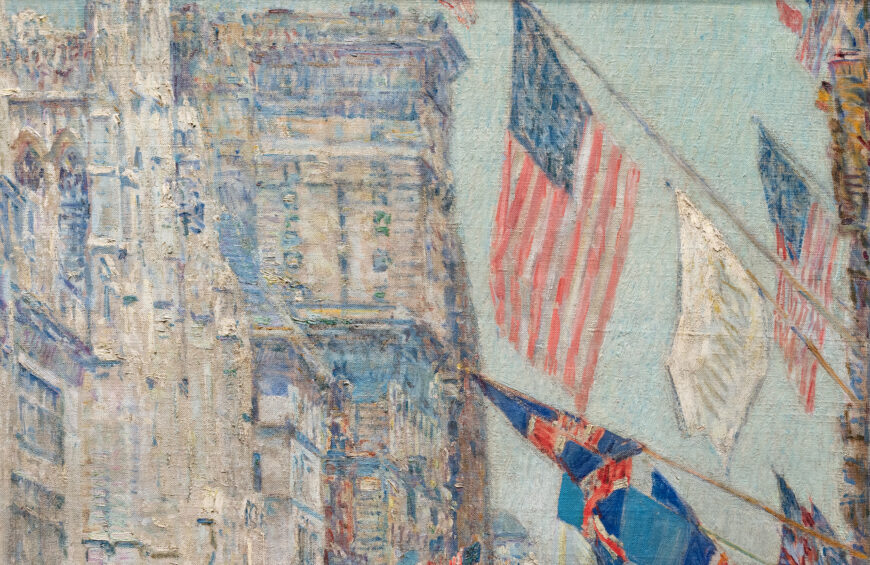

Dr. Harris: [0:41] I keep thinking about Monet’s lifelong desire to capture the beauty of the optical world, from when he was in Paris, and then in Argenteuil, and thinking back to the “Boulevard des Capucines” and the light flooding down the boulevard, to the “Gare Saint-Lazare” and the light filtered through the steam of the trains, and then later in his life, in his garden with the water lilies.

Dr. Zucker: [1:06] He was interested not only in capturing and understanding, rendering those effects of light and the momentary, but actually in creating them.

[1:16] He devoted an enormous amount of his life to actually planting these gardens and maintaining them, and then translating them onto canvas and in a sense preserving that sense of the momentary.

Dr. Harris: [1:27] The thing that I keep thinking about as we look at these and the intensity of the color and the beauty of the color harmonies is that the paintings are more beautiful than reality.

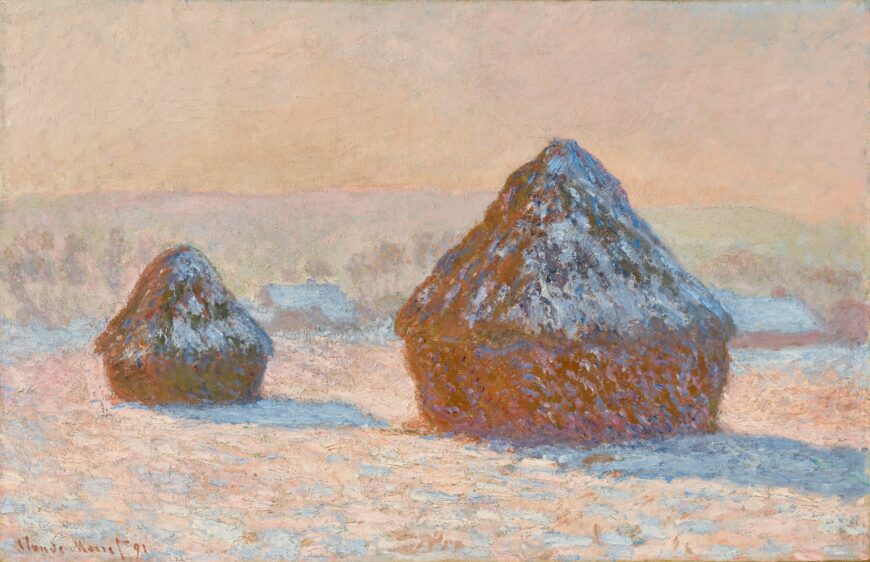

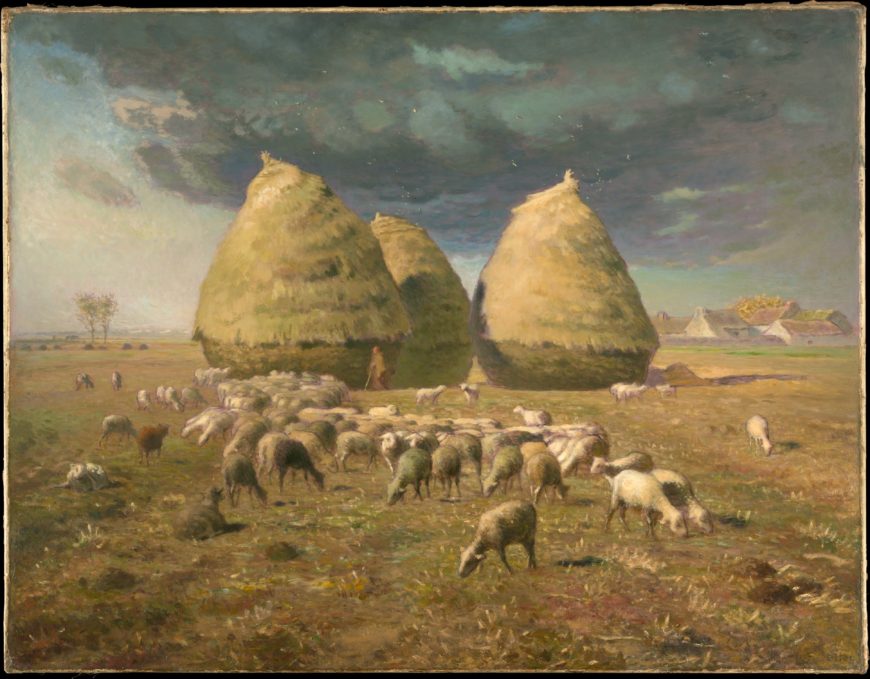

[1:38] Let’s think about them for a second in the history of landscape painting. These are unprecedented in that way. First of all, their shape is these very long panels without a horizon line.

Dr. Zucker: [1:49] Right. We’re looking across the water, so that we see neither the ground that we stand on nor the horizon on the far side.

Dr. Harris: [1:56] Traditional landscape painting often provided a path for one’s eye to travel through a landscape. Here, we really can’t do that because we’re confronted with the surface of the water, the surface of the paintings themselves.

Dr. Zucker: [2:11] I do think that Monet is borrowing actually from the classical tradition of landscape painting. If you look on both sides of these canvases, you see the dark shadows of the weeping willows, and those function in a sense the way that trees often framed recessionary landscapes by Claude or by Poussin.

[2:28] Monet has placed us in a very particular place. Obviously we’re on the shore in some way, but we’re looking across the water so that we see neither the ground that we stand on nor the horizon on the far side.

[2:40] Now, Monet had just enlarged his ponds, but even then they’re quite small, and so he’s really unmoored us by not giving us ground to stand on. But he has given us a very particular angle at which we’re viewing the pads of the water lilies themselves, and that does place us in relationship to the surface of the water so we actually can locate ourselves.

[3:01] They also allow us to hop, skip, and jump from pad to pad and move back into space, and then this extraordinary volume of space below the pond and the incredible dome of space above where those towering clouds ride above us.

[3:17] This sense of the extent of the volume that’s portrayed, and yet [to have] done so on the two-dimensional surface of the pond, which is of course a reflection of the two-dimensional surface of the canvas, is a beautiful summation of this notion that Monet has worked towards for so long.

[3:35] How does one capture both the abstraction of modern art and yet also still make room for the volume that our eye knows?

Dr. Harris: [3:47] There’s something really sublime here. We have the infinity of that depth and there’s also a sense of the infinite in the sky and the clouds, and that speaks back to that religious sense. While he’s capturing the transitory, there’s a sense of permanence and transcendence at the same time.

Dr. Zucker: [4:07] I think that’s actually a perfect way to state it. Let’s take a really close look at the paint.

[4:14] The surface is incredibly rich and rough and built up. You can see this kind of dry brush that Monet has pulled the paint across. What seems to happen is the paint comes off on the ridges that are already there, making those even more prominent.

Dr. Harris: [4:32] This almost has a sculptural surface that helps to create some senses of volume as you look across it.

[4:39] Toward late in his career, he wasn’t so interested in capturing things quickly. He wanted to be able to return to a painting and continue to work it. He’s finding a solution to that problem and creating a studio out-of-doors where he can continue to work the surface, and so it does have that feeling of something that has layers and layers of paint, where the paint has been allowed to dry and then he’s put on new layers.

Dr. Zucker: [5:03] When we stand close to this canvas and we see those layers of paint and we see the way they — almost like a tapestry — lie over each other so that we can see the paint between strokes and the colors are not so much blended as overlaid.

Dr. Harris: [5:15] It’s hard not to think about all-over painting and Jackson Pollock. The way that the painting occupies our field of vision. How did he escape that field of vision in order to paint the landscape?

[5:29] You can almost imagine this way that the painting becomes, as it did for Jackson Pollock, a world unto itself that the artist enters and exists within and we do too, actually, within the space of this room.

Dr. Zucker: [5:42] That’s a really critical point. What begins to happen with the early modernists, certainly with Matisse and Picasso and ultimately with people like Pollock, and maybe here, too, is the conversation ceases to be a dialogue between the artist and its subject, and becomes, ultimately, a dialogue between the artist and the canvas. That seems to have happened here to beautiful result.

[6:05] [music]