Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

J. M. W. Turner, Slave Ship

[0:00] [music]

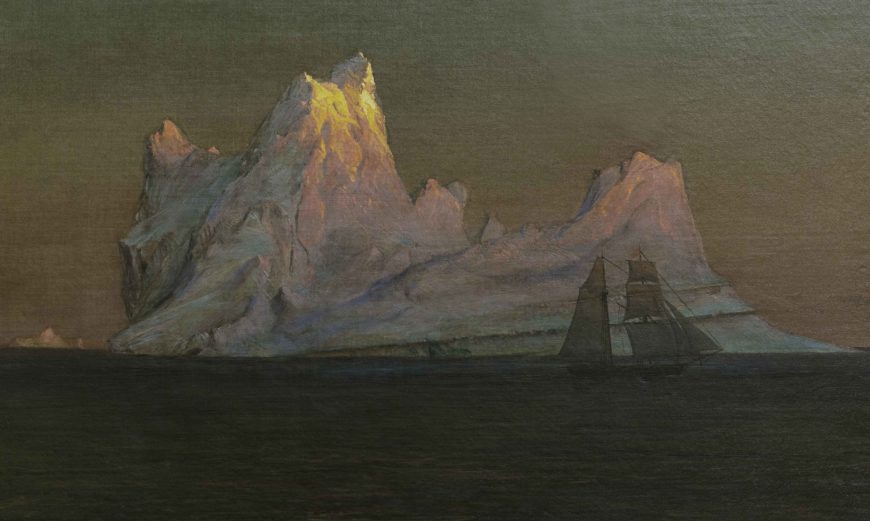

Lori Landay: [0:04] We’re standing in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in front of what we know as Turner’s “Slave Ship,” but the full title of this work is “Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On).”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:18] You know, when we first come across this painting, it looks really beautiful. It’s got oranges and reds, and we see that typical Turner sunset. We’re lost in the thick sensuality of the paint.

Lori: [0:31] But then my eye goes to the bottom right-hand corner, and in a moment of horror, I see a foot, and a leg, and a shackle, and chains, and all of a sudden it’s not a seascape. It’s not about a sunset and it’s not about light on the water or not only about those things anymore.

Dr. Harris: [0:52] There’s real carnage in front of us, in fact, in the closest part of the painting towards us. We’re looking at image of a slave ship that we can see in the distance. This is a ship carrying slaves and a typhoon has come on. This is based on a poem, but we know that this is something that happened in reality, not just once but many times.

[1:13] With the storm coming, the captain of the ship decided to throw the slaves overboard. Apparently, that was the only way you could collect the insurance. If the slaves died of illness or other things while on board, the captain of the ship couldn’t claim insurance. What he’s done is he’s thrown the slaves overboard and that’s what we see happening.

Lori: [1:34] It is really horrifying. We only see parts of their bodies, and there’s a swirl of waves and colors. And again, there’s this mixture of the beauty of nature, the power of nature, and this horrific human act that is within the context of a much wider horrific human act of slavery.

Dr. Harris: [1:55] We do have this sense of divine retribution, the storm coming for that slave ship that’s been dealing in human lives, and the punishment wreaked by nature is justified on that ship. But there’s also a sense of the total indifference of nature, because the same storm that’s going to overcome that slave ship is also going to drown the slaves themselves.

Lori: [2:20] Nature is completely indifferent to the human endeavors, whether they are good, evil, otherwise, whatever.

Dr. Harris: [2:28] The first owner of this painting was the great Victorian art critic John Ruskin. Then the painting made its way to Boston to an abolitionist, to someone who believed in and struggled for the ending of slavery.

[2:41] Now, the British had outlawed slavery in 1833 in the colonies. The French do it in their colonies 15 years later, but of course, in America, slavery isn’t outlawed until the Civil War. So slavery, we have to remember, is still a really active political cause at this moment.

[2:58] This idea that human beings could do this to each other, not just in the form of actual slavery — of buying and selling human beings — but also in terms of taking advantage of one another just for the sake of money. Of course, that’s the kernel of this hideous act that the captain engages in here.

Lori: [3:16] When we look into the left border of the painting, we see some really different colors than what we see in the rest of the painting. Whites and blues, purples and greys.

Dr. Harris: [3:30] Ruskin wrote, “Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shallow of death upon the guilty ship, as it labors amidst the lightning of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood.”

[3:50] [music]

| Title | Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) |

| Artist(s) | J. M. W. Turner |

| Dates | 1840 |

| Places | Europe / Western Europe / England |

| Period, Culture, Style | Romanticism |

| Artwork Type | Painting / Landscape painting |

| Material | Oil paint, Canvas |

| Technique |

Loading Flickr images...