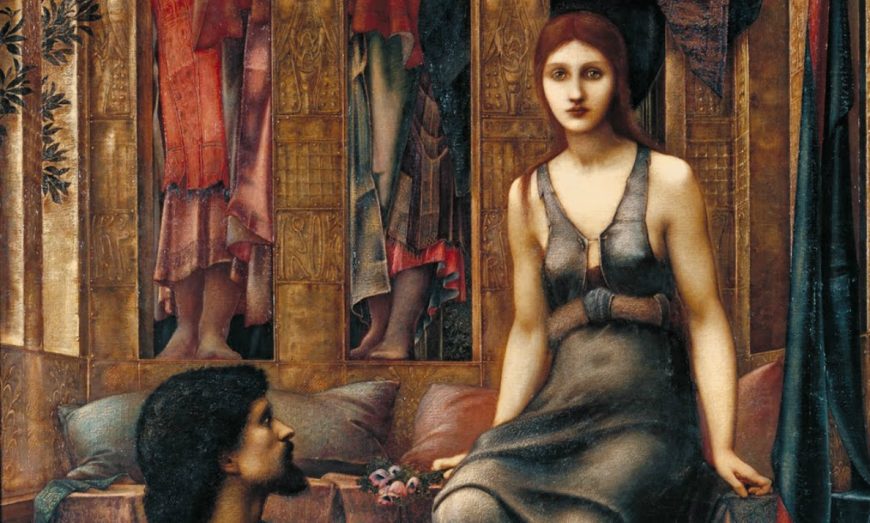

A princess falls under a spell and sleeps for a hundred years—but Burne-Jones never shows us the kiss that awakens her.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Briar Rose (The Briar Rose, The Council Chamber, The Garden Court, and The Rose Bower), c. 1890, oil on canvas (Buscot Park). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker