Henry Wallis, Chatterton, 1856, oil on canvas, 622 x 933 cm (Tate Britain, London).

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re in Tate Britain, and we’re looking at Henry Wallis’ “Chatterton” from 1856.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:10] Chatterton was an 18th-century writer who killed himself when he was 17 years old with arsenic, and that’s what’s being depicted here.

Dr. Harris: [0:17] Chatterton was a very popular figure among Romantic writers. He was the misunderstood genius who was exploited and underpaid for his craft.

Dr. Zucker: [0:26] Chatterton would have a relatively successful commercial career as a writer in London. That’s not to say that he was well paid, but he was well published.

Dr. Harris: [0:35] When his account book was looked at after his death, it turns out that Chatterton had been really underpaid for his writing.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] What’s most interesting is not so much the life of Chatterton, the subject, but the treatment that Chatterton receives in the 19th century.

Dr. Harris: [0:49] I think that one reason for his popularity among the Romantics was this idea of the misunderstood and underpaid artist, who I think many artists of the 19th century could relate to.

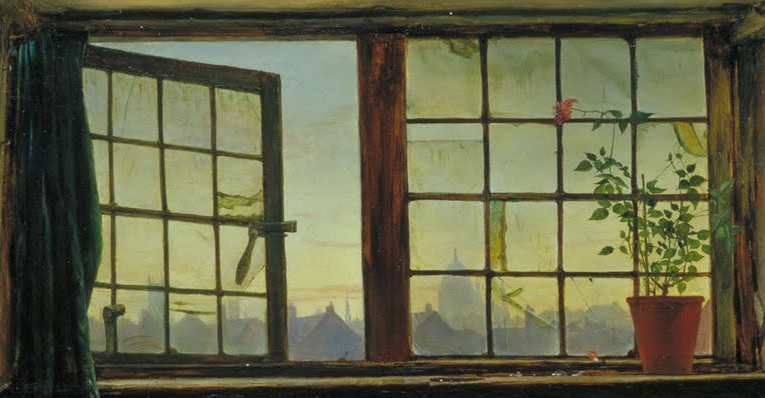

Dr. Zucker: [1:01] Let’s take a look at Wallis’ treatment. You have the figure backlit, light coming in from the small window in this garret, a small attic-like space that would be let out to the less fortunate.

Dr. Harris: [1:11] You can see outside a view of Saint Paul’s, the city of London where Chatterton lived. And then other signs of poverty — a small wooden table, a very spare candleholder where the candle’s been completely burned down. You can just make out the smoke rising.

Dr. Zucker: [1:28] Of course there’s symbolism there, the candle has burned down, [which] suggests the end of his life.

Dr. Harris: [1:32] We also see a rose that has similar significance. It’s dying there, its petals are accumulating on the windowsill. It doesn’t have much longer.

Dr. Zucker: [1:41] None of this is generalized. All of this is extraordinarily specific. The handling, the rendering is so much in the Pre-Raphaelite style. There is a strong linear quality and particularity. Look, for instance, at the vividness of the shadows cast by the knots on the bedspread.

[1:58] There is this recognition of the value of this precise handling of the most seemingly insignificant element of this room.

Dr. Harris: [2:07] We also see a lot of precision in the torn-up writings that we see on the left, and the gleaming metal of the latch of that trunk, and the way that light just shines slightly on the interior.

Dr. Zucker: [2:19] There’s also a very unusual use of color for mid-19th-century painting. Look at his red hair against the greenish cast of his skin, or the way that the artist is playing light and deep blues against the purples in his breeches.

Dr. Harris: [2:33] And those colors come alive even more because of that brown coverlet.

Dr. Zucker: [2:37] And the fact that Wallis, like other Pre-Raphaelites, is painting on a white ground rather than painting on a dark ground. The painting is full of specific anecdotes of the story. You can see, down by his hand, not only his shoe has been cast off, but you can see the bottle of arsenic.

Dr. Harris: [2:52] He’s very much in the pose of a Pietà, so we can really think of him as an artist-martyr, like Christ himself. I think that idea that it was a difficult time for artists is an important one. It’s now the general public that is the audience and the patron for artists, and that put artists in a really precarious position.

Dr. Zucker: [3:13] Well, this is interesting, because in the history of art the patrons had been the church and then the aristocracy, but here, now, in our new industrial society, art is one more commodity. There was an interest in what that meant for somebody who was a creative genius.

[3:29] [music]

A tragic suicide

Chatterton by Henry Wallis is an example of the Victorian approach to history painting. The picture illustrates the suicide of the poet Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770). Despairing over his lack of literary success, the young poet tore up his manuscripts and took a lethal dose of arsenic.

Henry Wallis, Chatterton, 1856, oil on canvas, 622 x 933 cm (Tate Britain, London)

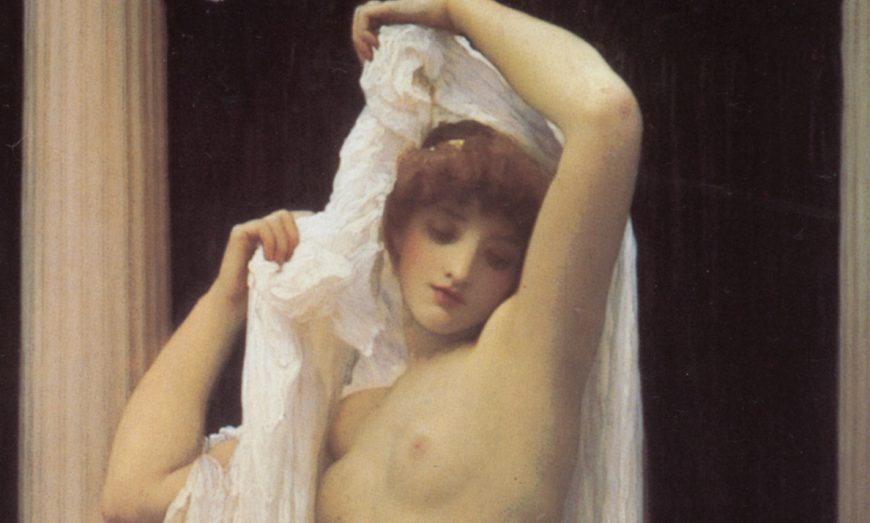

Henry Wallis, Chatterton, 1856, oil on canvas, 622 x 933 cm (Tate Britain, London)Wallis’s shows the pale, still body of Chatterton lying on a bed, his head and right arm dangling loosely over the edge, his tattered papers and the poison vial beside him. His white shirt and stockings help to silhouette the figure against the darker background, while the vivid purple of Chatterton’s knee breeches and his reddish hair grab the viewer’s attention.

Tattered papers (detail), Henry Wallis, Chatterton, 1856, oil on canvas, 622 x 933 cm (Tate Britain, London)

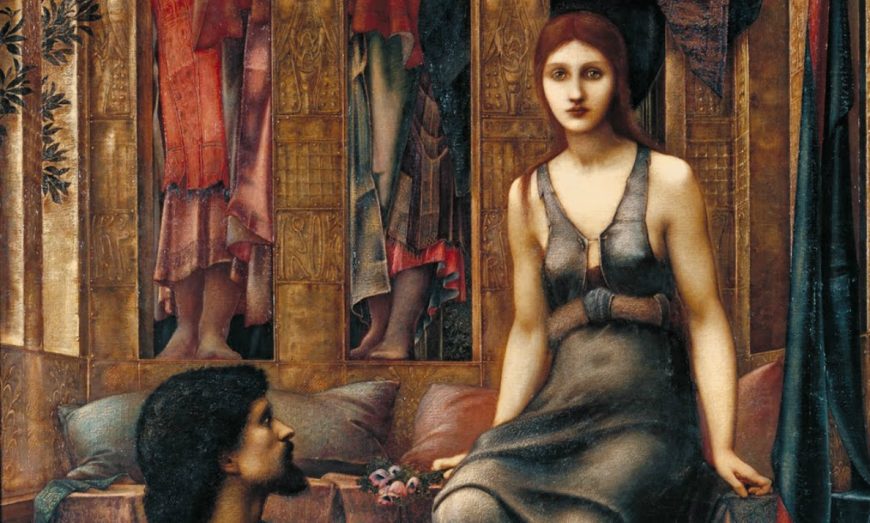

Above the body, an attic dormer window looks out at the sunrise across the city of London, with St. Paul’s Cathedral in the distance. Both the vivid colors of Chatterton’s pants and hair and the attention to detail in areas such as in coverlet on the bed and the clothing carelessly strewn off to one side, point to Wallis’s interest in the ideas of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His greatest deviation from “truth to nature” was in his choice of model. George Meredith, another struggling author, was depicted as the dead Chatterton, since no actual portraits of the poet were available to copy. This collaboration was not to be repeated, however, as Wallis later eloped with Meredith’s wife.

View of the city (detail), Henry Wallis, Chatterton, 1856, oil on canvas, 622 x 933 cm (Tate Britain, London)

A Victorian approach to history painting

Chatterton is typical of the Victorian interest in historical subjects. The Victorians were voracious readers, and history of all types—from scholarly tomes to sentimental historical novels—were frequently “best sellers.”

The goal of all types of history was to bring the past to life for the audience. To quote the Art Union from 1843

to make the past present…to place our ancestors before us, in all their peculiarities of their dress and time, until they seem not part of a personified allegory, but beings of flesh and blood; such are the duties which belong to the artist as well as the historian.

The almost sculptural beauty of the body of Chatterton and the aura of tragedy over the squandered potential of this youthful talent was clearly calculated to appeal to the sentimental Victorian public.

The work of Henry Wallis was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Born in London, Wallis was a student at the Royal Academy schools beginning in March 1848. He also studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and the studio of Gleyre in Paris, which set him apart from many of the other PRB artists. He began to exhibit in 1853 and his best know canvases come from early in his career as he spent much of his time traveling after his elopement.

Poison vial (detail), Henry Wallis, Chatterton, 1856, oil on canvas, 622 x 933 cm (Tate Britain, London)

Chatterton created a sensation when it was first exhibited in 1856 and again when it appeared at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857. John Ruskin called the painting “faultless and wonderful,” but for others it was a cautionary tale. The Victorian public could not fail to understand the moral message of a talented life tragically cut short. Wallis’s Chatterton is a brilliant combination of history, romanticism, and truth to nature.