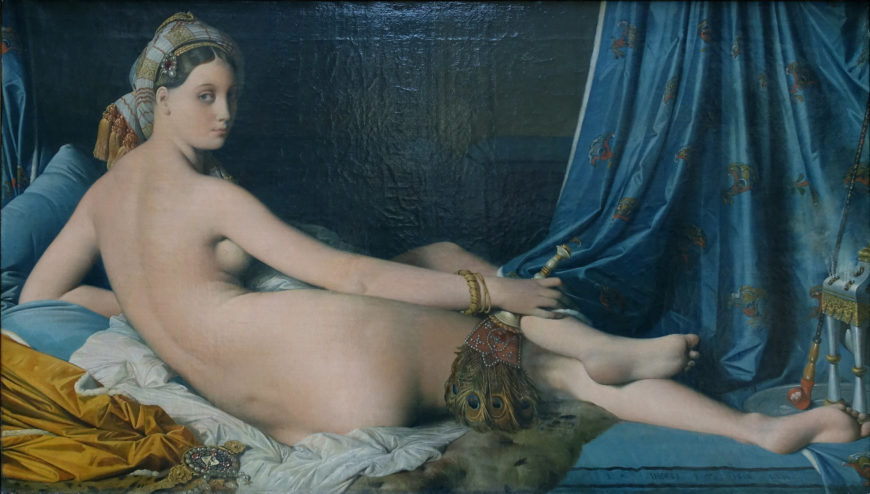

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Grand Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The origins of Orientalism

Snake charmers, carpet vendors, and veiled women may conjure up ideas of the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia, but they are also partially indebted to Orientalist fantasies. To understand these images, we have to understand the concept of Orientalism, beginning with the word “Orient” itself. In its original medieval usage, the “Orient” referred to the “East,” but whose “East” did this Orient represent? East of where?

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, 1480, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 52.1 cm (The National Gallery, London)

We understand now that this designation reflects a Western European view of the “East,” and not necessarily the views of the inhabitants of these areas. We also realize today that the label of the “Orient” hardly captures the wide swath of territory to which it originally referred: the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. These are at once distinct, contrasting, and yet interconnected regions. Scholars often link visual examples of Orientalism alongside the Romantic literature and music of the early nineteenth century, a period of rising imperialism and tourism when Western artists traveled widely to the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. We now understand that the world has been interconnected for much longer than we initially acknowledged and we can see elements of Orientalist representation much earlier—for example, in religious objects of the Crusades, or Gentile Bellini’s painting of the Ottoman sultan (ruler) Mehmed II (above), or in the arabesques (flowing s-shaped ornamental forms) of early modern textiles.

The politics of Orientalism

In his groundbreaking 1978 text Orientalism, the late cultural critic and theorist Edward Saïd argued that a dominant European political ideology created the notion of the Orient in order to subjugate and control it. Saïd explained that the concept embodied distinctions between “East” (the Orient) and “West” (the Occident) precisely so the “West” could control and authorize views of the “East.” For Saïd, this nexus of power and knowledge enabled the “West” to generalize and misrepresent North Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Though his text has itself received considerable criticism, the book nevertheless remains a pioneering intervention. Saïd continues to influence many disciplines of cultural study, including the history of art.

Representing the “Orient”

As art historian Linda Nochlin argued in her widely read essay, “The Imaginary Orient,” from 1983, the task of critical art history is to assess the power structures behind any work of art or artist. [1] Following Nochlin’s lead, art historians have questioned underlying power dynamics at play in the artistic representations of the “Orient,” many of them from the nineteenth century. In doing so, these scholars challenged not only the ways that the “West” represented the “East,” but they also complicate the long held misconception of a unidirectional westward influence. Similarly, these scholars questioned how artists have represented people of the Orient as passive or licentious subjects.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Snake Charmer, c. 1879, oil on canvas (The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts)

For example, in the painting The Snake Charmer and His Audience, c. 1879, the French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme’s depicts a naked youth holding a serpent as an older man plays the flute—charming both the snake and their audience. Gérôme constructs a scene out of his imagination, but he utilizes a highly refined and naturalistic style to suggest that he himself observed the scene. In doing so, Gérôme suggests such nudity was a regular and public occurrence in the “East.”

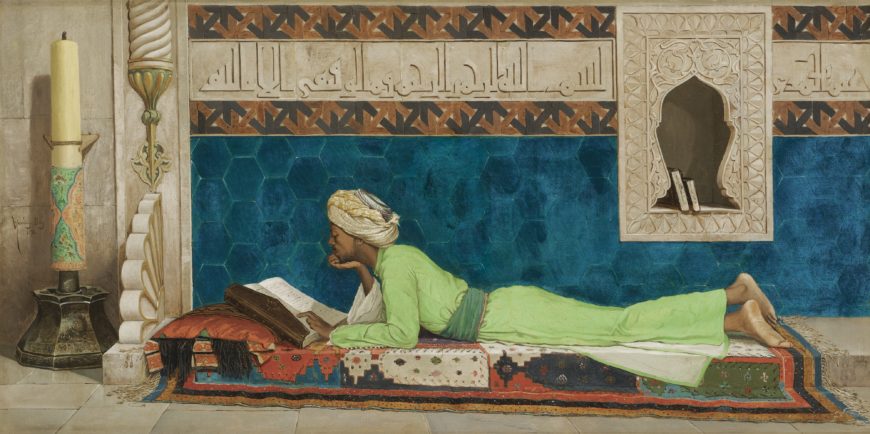

In contrast, artists like Henriette Browne and Osman Hamdi Bey created works that provide a counter-narrative to the image of the “East” as passive, licentious or decrepit. In A Visit: Harem Interior, Constantinople, 1860, the French painter Browne represents women fully clothed in harem scenes. Likewise, the École des Beaux Arts-trained Ottoman painter Osman Hamdi Bey depicts Islamic scholarship and learnedness in A Young Emir Studying, 1878.

Osman Hamdi Bey, A Young Emir Studying, 1878, oil on canvas (Louvre Abu Dhabi)

Orientalism: fact or fiction?

Orientalist paintings and other forms of material culture operate on two registers. First, they depict an “exotic” and therefore racialized, feminized, and often sexualized culture from a distant land. Second, they simultaneously claim to be a document, an authentic glimpse of a location and its inhabitants, as we see with Gérôme’s detailed and naturalistic style. In The Snake Charmer and His Audience, Gérôme constructs this layer of exotic “truth” by including illegible, faux-Arabic tilework in the background. Nochlin pointed out that many of Gérôme’s paintings worked to convince their audiences by carefully mimicking a “preexisting Oriental reality.” [2]

Surprisingly, the invention of photography in 1839 did little to contribute to a greater authenticity of painterly and photographic representations of the “Orient” by artists, Western military officials, technocrats, and travelers. Instead, photographs were frequently staged and embellished to appeal to the Western imagination. For instance, the French Bonfils family, in studio photographs, situated sitters in poses with handheld props against elaborate backdrops to create a fictitious world of the photographer’s making.

Bonfils family, Young Woman from Lebanon in Party Dress, undated, albumen print, 10 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches (courtesy of McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture, The University of Tennessee)

In Orientalist secular history paintings (narrative moments from history), Western artists portrayed disorderly and often violent battle scenes, creating a conception of an “Orient” that was rooted in incivility. The common figures and locations of Orientalist genre paintings (scenes of everyday life)—including the angry despot, licentious harem, chaotic medina, slave market, or the decadent palace—demonstrate a blend of pseudo-ethnography based on descriptions of first-hand observation and outright invention. These paintings created visions of a decaying mythic “East” inhabited by a controllable people without regard to geographic specificity. Artists operating in this vein include Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and others. In the visual discourses of Orientalism, we must systematically question any claim to objectivity or authenticity.

Global imperialism and consumerism

We also must consider the creation of an “Orient” as a result of imperialism, industrial capitalism, mass consumption, tourism, and settler colonialism in the nineteenth century. In Europe, trends of cultural appropriation included a consumerist “taste” for materials and objects, like porcelain, textiles, fashion, and carpets, from the Middle East and Asia. For instance, Japonisme was a trend of Japanese-inspired decorative arts, as were Chinoiserie (Chinese-inspired) and Turquerie (Turkish-inspired). The ability of Europeans to purchase and own these materials, to some extent confirmed imperial influence in those areas.

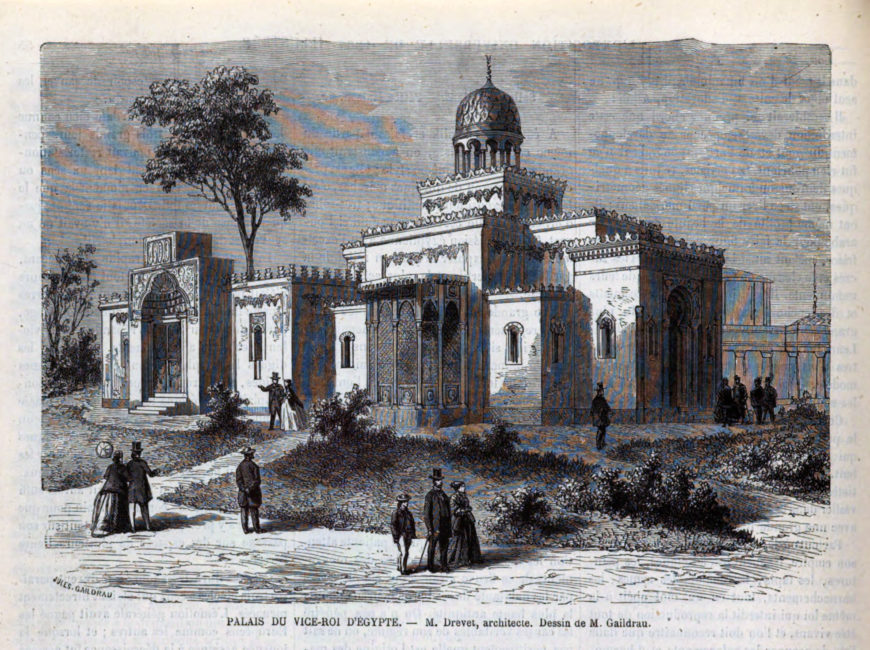

Palace of the Khedive, L’Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée, Paris, p. 56 (Bavarian State Library, Munich)

The phenomenon of World’s Fairs and cultural-national pavilions (beginning with the Crystal Palace in London in 1851 and continuing into the twentieth century) also supported the goals of colonial expansion. Like the decorative arts, they fostered the notion of the “Orient” as an entity to be consumed through its varied pre-industrial craft traditions.

We see this continually in the architectural imitations built on the grounds of these fairs, that sought to provide both spectacle and authenticity to the fair goer. For instance, at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the designers of the Egyptian section Jacques Drévet and E. Schmitz topped what was supposed to represent the residential khedival (Ottoman Empire ruler’s) palace with a dome typical of mosque architecture. [3] Yet, they also attached to this building a barn (not typical of a khedival palace) that housed imported donkeys brought in to give visitors the impression of reality. [4] The fairs objectified the otherness of non-Western peoples, cultures, and practices.

Orientalism constructs cultural, spatial, and visual mythologies and stereotypes that are often connected to the geopolitical ideologies of governments and institutions. The influence of these mythologies has impacted the formation of knowledge and the process of knowledge production. In this light, as Saïd and Nochlin remind us, when we see Orientalist works like Gérôme’s Snake Charmer, we should ask what idea of the “Orient” we see, and why?