Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace, Lartos marble (ship) and Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E. 3.28 m high, Hellenistic Period (Musée du Louvre, Paris); a conversation between Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Standing at the top of a staircase in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Nike of Samothrace looks down over her admiring crowds. One of the most revered artworks of Hellenistic Greek art, the Nike has been on display in the Louvre since 1866. The statue was brought to France by Charles Champoiseau, who found it in pieces during excavations on the island of Samothrace in 1863. Champoiseau was serving as vice-consul in the Ottoman city of Adrianople (modern Edirne, in Turkey), and visited Samothrace specifically to look for antiquities. At the time, European travelers and archaeologists, as well as many amateurs like Champoiseau, conducted excavations and combed ancient sites in the eastern Mediterranean in search of ancient objects to display in their homes and museums. The ownership of ancient objects highlighted appreciation for and connection to the antique past and was understood as a as sign of elite status.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Announcing a naval triumph

The sculptural group consists of two parts, a large ship’s bow made of grey marble and a free-standing white marble statue with the overall composition rising more than eighteen feet (Nike alone is nine feet tall). The flying personification of victory (nikē in Greek means victory) alights on top of the ship, announcing a naval triumph. Her wings stretch dramatically behind her. A forceful wind blows her drapery across her body, gathering it in heavy folds between her legs, around her waist, and streaming behind her, conveying a vivid illusion of movement. Thin and gauzy across her breasts, abdomen, and legs, this same drapery reveals her body underneath the clothing, creating an erotized vision of the female form.

Similar to other Hellenistic artworks such as the Laocöon and the Great Altar at Pergamon, the Nike is extraordinarily dramatic in composition and style. It is intended to be viewed from multiple angles, encouraging the viewer to move around the statue, and through this interaction engage with the artwork physically and emotionally.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Right hand , Nike of Samothrace, c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: 林高志, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The statue, as it stands today in the Louvre, has been partially restored. While it is now plain white marble, the statue, like all ancient Greek and Roman marble sculptures, would have originally been brightly painted, and traces of pigment have been found on the statue. The right wing is a modern replica. Surviving fragments indicate that the right wing would have risen higher than the left wing and slanted upward. The missing feet, arms, and head have not been restored, giving the statue its now iconic form.

Nike’s surviving right hand (which was found in 1950) gives a clue to her original appearance. Her fingers are outstretched, indicating that she may have been making a gesture of greeting.

Nike, c. 200–150 B.C.E., terracotta, from Myrina, Anatolia (The British Museum; photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A series of small terracotta figurines of Nike, made in Myrina in Anatolia, give further insight into the original appearance of the Nike of Samothrace. These statues show the goddess in flight, her drapery blown by the wind, with her wings stretched behind her balanced by her extended arms in front. Nike of Samothrace most likely appeared similarly, but on a much larger scale.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nike’s wings are a mastery of marble construction. Marble is a heavy material, and compositions that included large protruding, unsupported, large elements such as the wings were rarely seen in earlier Greek sculpture. The now-unknown artist(s) of the Nike of Samothrace solved this problem by creating slots on Nike’s back into which the wings were inserted, and designing the wings with a downward slope so that the weight of the wings rested primarily against the body and did not need an external support.

Nike of Paionios, c. 420 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Who was Nike?

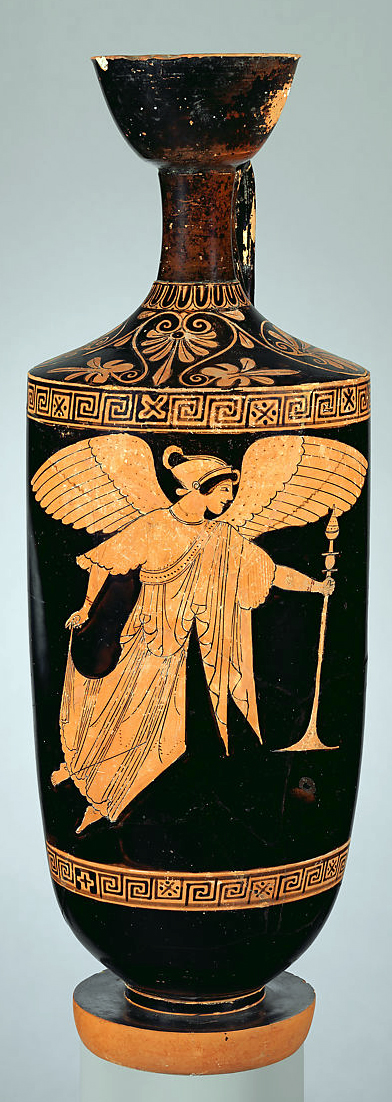

Nike on a Terracotta lekythos, c. 490 B.C.E., attributed to the Dutuit Painter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Nike was both the goddess of victory and the personification of victory itself, in both war and athletic competitions. She was rarely featured in Greek myth and had no easily definable personality or biography. She was usually worshipped alongside other gods or as an attribute of another deity, such as Athena Nike (Athena Bringer of Victory) on the Athenian Acropolis. Yet, she was regularly featured in Greek art, appearing on pots, architectural sculpture, and free-standing sculptural compositions, either singly or in multiple.

Her iconography is distinctive—a winged, youthful woman—and she is one of the most easily identifiable Greek mythological figures. She crowns gods and victorious athletes with leafy circlets or holds palm fronds symbolizing victory. She was the perfect subject to commemorate military triumphs and was regularly featured in victory monuments, notably the fifth-century Nike of Paionios, erected at the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia to celebrate a Peloponnesian War victory.

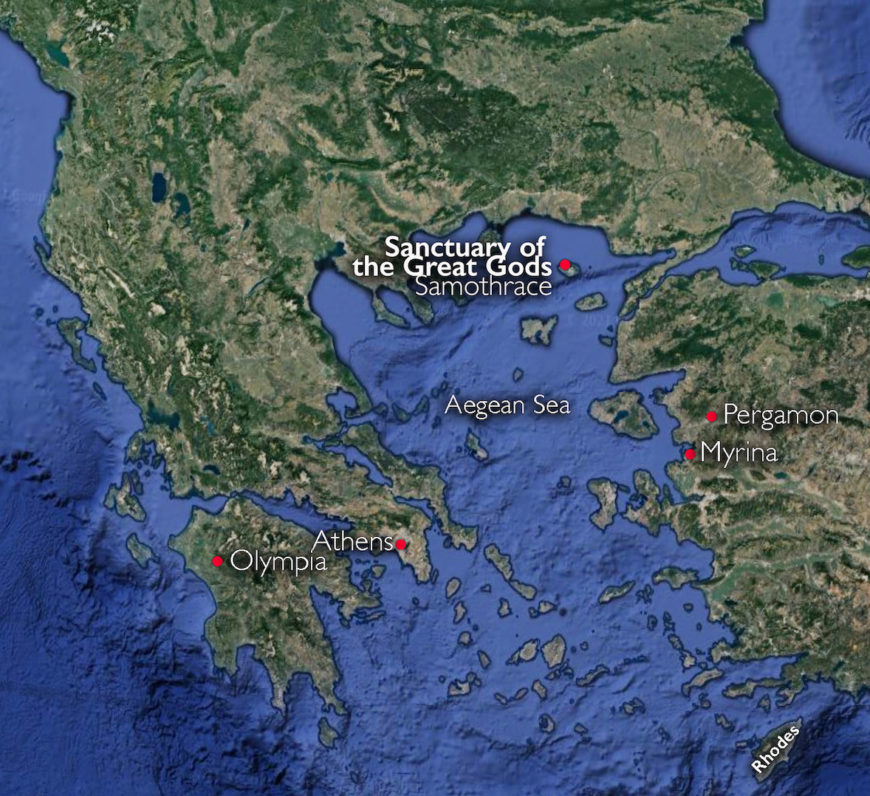

Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace

The Nike of Samothrace was originally erected as a military victory monument in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods (Theoi Megaloi) on Samothrace, a small island in the northern Aegean Sea. While the permanent population of the island was relatively small, an influx of worshippers regularly descended upon Samothrace to participate in religious rites hosted by the sanctuary, especially in the Hellenistic and Roman periods when the sanctuary was at its height of popularity. The cult of the Great Gods was a mystery religion, meaning that worshippers needed to be initiated into the cult before they were allowed to participate, and the rites were kept secret from everyone except the initiates. Since secrecy was so central to the cult, modern scholars do not know exactly what was involved in the rituals. However, we do know that the cult promised its initiates safety at sea and personal moral benefit.

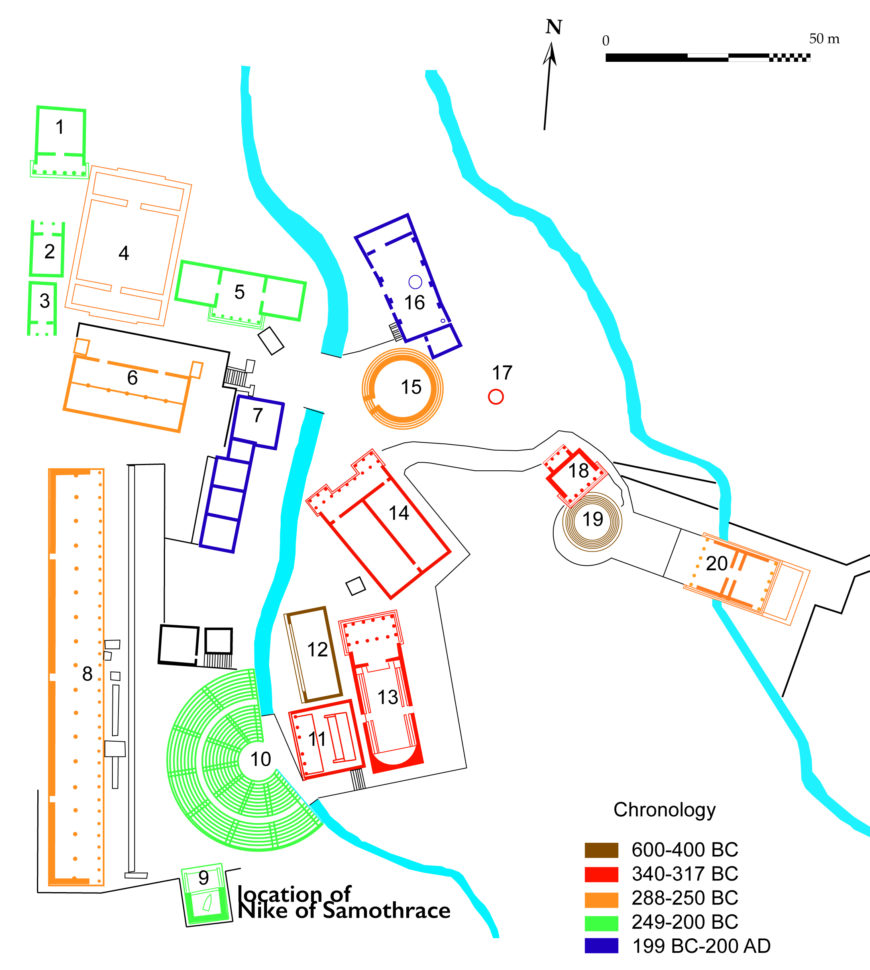

Plan of the sanctuary of the Great Gods, Samothrace, with the location of Nike of Samothrace at location 9

Worshippers came from throughout the ancient Mediterranean to worship, and initiation was open to all, regardless of social class, gender, or citizenship. Royals, elites, commoners, and enslaved people were all initiated into the cult. The Roman writer Plutarch even says that the parents of Alexander the Great, Philip and Olympias, met while they were initiates on Samothrace.

The sanctuary was located in a narrow valley, with buildings located on the valley floor and on terraces cut into the hillsides. The Nike monument was on the west slope, in a niche at the top of the hill behind the theater. Placed at one of the highest points in the sanctuary, it would have been visible from numerous viewpoints as initiates moved through rituals.

Scholars once believed the Nike of Samothrace stood in a fountain. Archaeological evidence for this theory has now been shown to post-date the monument, and while there is still debate about whether the structure was roofed or enclosed by walls, scholars today hold that the Nike group was housed in a small building, open on the north side, with the Nike facing out over the theater. The illusion of her blowing drapery would have been reinforced by the actual onshore wind that would have blown across the valley.

Dedication and historical context

Due to the popularity of the cult, and its connection to protection at sea, it makes sense that a military leader would have dedicated a monument commemorating a naval victory at Samothrace. The triumphant commander would have proclaimed his victory before an international audience, including perhaps those he defeated. The dedicatory inscription, which most votive statues in Greek sanctuaries included, has not survived, so it is unknown who dedicated the statue or what victory it commemorated.

Left: Athena panel, east frieze, Pergamon Altar, c. 197-139 B.C.E. (Staatliche Museen, Berlin); right: Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Based on stylistic similarities between the Nike of Samothrace and the external frieze of the Great Altar at Pergamon, notably its theatricality and hyperrealism, the statue is usually dated to the first half of the second century B.C.E. In the period, naval battles between the Hellenistic kingdoms were common as they fought for military, political, and economic control. The Greek Hellenistic world stretched from mainland Greece through Egypt, across Anatolia and the Near East to central Asia. The territory was divided into a series of empires. While most were hereditary monarchies, rulership was frequently unstable; power regularly changed hands and borders shifted. Many of these shifts in power were determined through warfare, and a strong military was a key part of a leader’s ability to hold onto his throne. The Hellenistic dynasts carefully built up their armies and navies, attempting to outdo one another both in the size of their forces and the advancement of their military technology. Triumphs were widely advertised, and victory monuments were an important part of royal propaganda. Erected both at home and at sites like Samothrace, they ensured that the nation’s subjects, allies, and enemies knew of an empire’s military might.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0))

Scholars have proposed a number of possible battles that the Nike of Samothrace commemorated, but most theories argue that the statue commemorated a victory over the island of Rhodes. This is based in part on the material of the ship on which Nike stood, a grey marble from the Lartos quarries on Rhodes. The Nike herself is made of a white Parian marble, which was revered as a superior material for sculpture, and exported throughout the Mediterranean. Lartian marble was much less commonly used, and we see it primarily in monuments on Rhodes or commissioned by Rhodians. In addition, the amount of marble used in the Nike of Samothrace was large, weighing around 30 tons, and would have been a full shipload on a typical merchant ship. Given the cost to ship the marble from Rhodes, it was likely specially ordered and intended to make a statement, connecting it to the Rhodians.

Tetradrachm (coin) showing Nike blowing a trumped, 301–295 B.C.E., minted by Demetrius Poliorcetes, silver (Münzkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin)

The form of a naval victory monument featuring a carved marble ship appears to be a popular type in the Hellenistic period, and parallels for the Nike of Samothrace are widespread—they have been found in mainland Greece, the Aegean islands, and Cyrene in Libya. The closest parallel appeared on coins minted by Demetrius Poliorcetes of Macedonia at the end of the third century B.C.E. The coins depict Nike on the prow of a ship, blowing a horn to announce a victory.

The Nike of Samothrace, while originally located in a sanctuary on a small island in the north Aegean, was intrinsically part of a Hellenistic world defined by the transmission of ideas, goods, people, and artistic motifs over large distances. Today, it is admired by an international audience in the Louvre, and its original intention was similar. The Sanctuary of the Great Gods, promising protection at sea to its initiates, was visited by worshippers from across the Mediterranean. The statue commemorated a naval triumph, and its placement in this location afforded it a broad audience, advertising its dedicator’s military prowess to the world. The Nike’s windswept drapery, outstretched wings, and dramatic location assured that it would have drawn the eyes of everyone who saw it.

Additional resources:

Nike of Samothrace and the Daru Staircase on the Louvre website

A Closer Look at the Victory of Samothrace from the Louvre

Nike of Samothrace on the American Excavations at Samothrace website

Kevin Clinton, et al. “The Nike of Samothrace: Setting the Record Straight,” American Journal of Archaeology 124, no. 4 (2020): pp. 551–573.

Ira S. Mark, “The Victory of Samothrace.” In Regional Schools in Hellenistic Sculpture: Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, March 15-17, 1996, edited by Olga Palagia and William Coulson (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2017), pp. 157–166.

Olga Palagia, “The Victory of Samothrace and the Aftermath of the Battle of Pydna.” In Samothracian Connections: Essays in Honor of James R. McCredie. Edited by Olga Palagia and Bonna D. Wescoat (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2010), pp. 154–64.

Andrew Stewart, “The Nike of Samothrace: Another View,” American Journal of Archaeology 120, no. 3 (2016), pp. 399–410.

Bonna D. Wescoat, et al. “Interstitial Space in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace.” In Hellenistic Architecture and Human Action: A case of Reciprocal Influence. Edited by Anette Haug and Asja Müller (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2020), pp. 41–62.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”samothrace,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re standing in the Louvre, looking at the very famous “Nike of Samothrace.” Now, a Nike personifies victory.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:11] And was the goddess of victory as well. This sculpture is 18 feet tall if you include the ship that she stands on. It’s placed at the top of one of the grand staircases. It is incredibly dramatic.

Dr. Harris: [0:23] She was found in pieces. She wasn’t found whole the way that we see her today, and she’s been reconstructed. The pieces that were missing have been filled in, and she was recently restored.

Dr. Zucker: [0:34] Originally this was placed in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on the island of Samothrace in the northeastern Aegean Sea. We should say that we have very little information about this particular cult.

[0:44] What we do have is a magnificent sculpture that was carved during the Hellenistic Period. This is after the Classical Period, after Alexander the Great created one of the largest empires the world had known to that date.

[0:56] It was a period when Greek art was extremely expressive, and in fact, art historians often pair this sculpture, in its style, with the sculpture that we find on the great frieze at the Altar of Zeus at Pergamon.

Dr. Harris: [1:10] In both cases, there’s a sense of energy and drama and power. Although we can compare the drapery that clings in these complex folds to the body to the sculptures on the earlier Parthenon, there’s so much more drama here.

Dr. Zucker: [1:25] I love the way in which the drape seems to be whipped by the wind. It’s interesting to note that the way that the ship would have been originally oriented, it would have been facing towards the coast, with the wind coming off the sea, and so the actual wind on Samothrace would have functioned as a collaborator with the illusion of the sculpture.

Dr. Harris: [1:42] Now, Nike figures are not unusual in ancient Greek art. To me, what’s so special about this figure is the tension between the lower half of the body and the upper half. She’s clearly alighting, landing on this ship.

[1:58] With the lower part of her body, I feel that pull downward, but the upper part of her body seems to still be held aloft, and so her torso stretches up and twists slightly in the opposite direction of her legs. So there’s this upward movement, but downward movement at the same time.

Dr. Zucker: [2:17] The sense of naturalism is so extraordinary that there seems to be nothing improbable about the wings attached to the shoulders of this figure. It just seems completely natural.

Dr. Harris: [2:27] It used to be thought that perhaps this figure stood within a fountain, and perhaps was blowing a trumpet, or offering a crown of victory, but we now think that her hand was simply outstretched, either she was in an open sanctuary or a slightly enclosed sanctuary.

[2:44] I love the pinkish-white, almost golden color of the marble that she’s carved from and the grayish color of the ship.

Dr. Zucker: [2:54] There’s a wonderful contrast between those two materials. Although she’s lost her head and both of her arms and other bits and pieces as well, we are so lucky to have this sculpture this intact.

Dr. Harris: [3:05] Well, think about all that’s been lost that didn’t survive and the incredible achievements of ancient Greek and specifically Hellenistic art.

[3:15] [music]