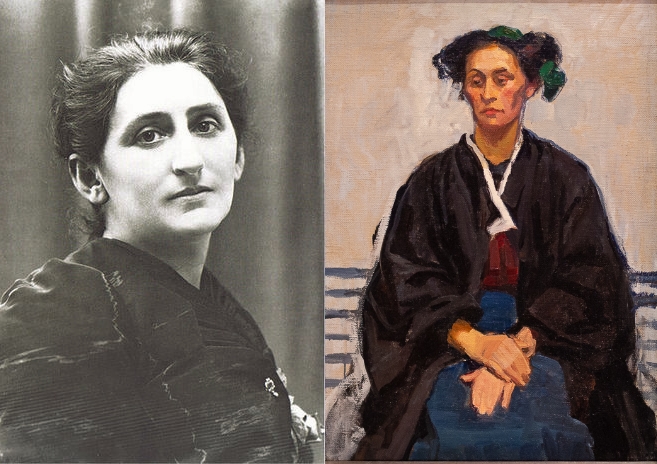

Broncia Koller, Sitting (Seated Nude Marietta), 1907, oil on canvas, 107.5 x 148.5 cm (Collection Eisenberger)

An unusual female nude

At first glance, we might take Broncia Koller’s Sitting (Seated Nude Marietta) as just another painting of a horizontal nude woman, hardly something rare in the history of European art (see Titian’s Venus of Urbino as an example). But another look persuades us that there is something different about this painting. Rather than lounging seductively and turning her body to the viewer, the subject here is in the act of sitting up attentively, her legs stretched out before her. She lacks both the marble smoothness and the ideal proportions of the typical female nude in western art history.

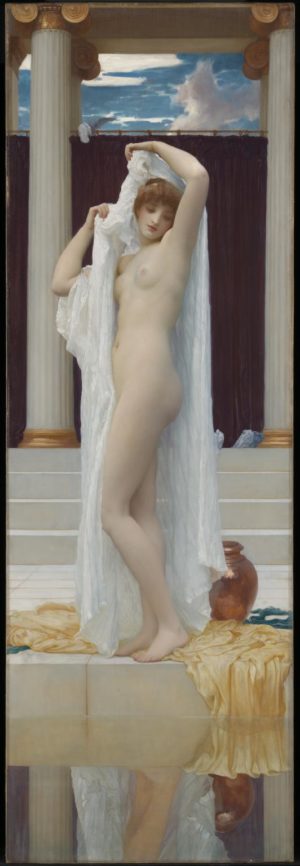

Frederic Leighton’s Bath of Psyche provides a good example of a 19th-century nude painted according to the principles laid down by the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Standing in a Greek bathhouse, Psyche’s body is as lean and polished as the Ionic columns and marble steps behind her. She casts the eyes of her face downward, allowing the viewer a vicarious look at her body as she removes her thin toga. Her pose, with raised arm, evokes both the classical nudes of antiquity (ancient Greek and Roman art), and allows for maximum visual consumption of her body.

Against the rules of both classical statuary and of Academic painting, Marietta reveals a small bit of pubic hair. Her soft stomach and thin arms lack the perfect proportions of Leighton’s Psyche and her skin neither glows nor resembles flawless stone. Instead of a coy expression, she fixes a curious and intent gaze back at the viewer. Her setting feels more reminiscent of a doctor’s office or a light-flooded studio than a Greco-Roman building or a sensual lair, removing the erotic undercurrent.

In contrast to the vertical format of Leighton’s work, the composition of Koller’s work is horizontal. Scholar Julie Johnson compares the sheet she sits on to the tablecloth under a still life, a comparison echoed as well in the shallow space and design of the work.

Perhaps Koller is reminding us that we’re looking at a painting, not a flesh and blood figure. Here, Marietta is an abstraction, a series of shapes and colors and textures. The artist draws our attention to the decorative and geometric qualities of the image, rather than any underlying sexual charge.

Abstraction and the aesthetic of the Secession

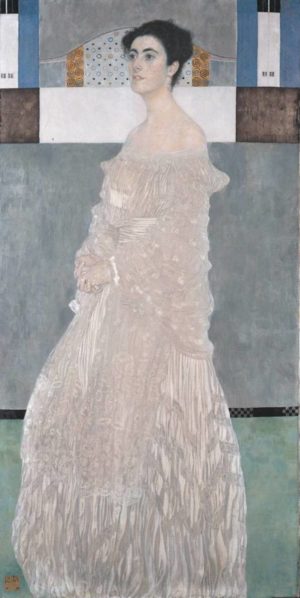

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, oil on canvas, 179.8 x 90.5 cm (Neue Pinakothek, Munich)

James McNeil Whistler, Harmony in Gray and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander, 1872–4, 190.2 × 97.8 cm (Tate)

The setting of the painting is stark. The artist has divided the background into a series of unequal squares and rectangles, which play against the triangles of the nude’s elbows, pubic region, and feet. In the asymmetrical squares and the framing of the figure’s head, the portrait recalls Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, painted two years earlier. So, too, does the play of diaphanous white against shades of grey, a subtle visual harmony that harks back to James McNeil Whistler’s nuanced portraits in monochrome and neutrals.

Koller’s nod to the portraiture of Klimt was deliberate. Both socially, and professionally, Koller’s art was bound to the circle of the Vienna Secession, a group of (male) artists working in the fine arts, architecture, and design, beginning in 1897. The leading lights of the Secession, such as Klimt, designer Kolomon Moser, and architect Josef Hoffmann were regular guests at the home of Koller and her husband, physician Hugo Koller, in Oberwaltersdorf (south of Vienna), as were notable musicians and philosophers. Koller exhibited in the all-important Kunstschauen (Art shows) of 1908 and 1909, alongside Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Oscar Kokoschka.

In 1913 Koller joined the Bund Österreichischer Künstler (Federation of Austrian Artists), a rare artistic group open to both men and women, alongside artists from the Wiener Werkstätte (an Arts and Crafts Cooperative founded in 1903) and the Secession. As scholars Megan Brandow-Faller and Julie Johnson have shown, the Vienna Secession was not open to women members, but Koller was clearly showing herself to have absorbed its many stylistic tenets.

Broncia Koller and Viennese modernism

Koller hailed from an upper middle-class Jewish family and began to study art seriously at the age of eighteen. Despite the radical modernism exploding in many domains of culture―from art, to psychoanalysis, to music―Vienna was a conservative city, where women were prohibited from studying at the Vienna Art Academy. Like many women, Koller found a way around this by taking private lessons and then going abroad to study in Munich. Rather than marrying in her 20s, like the vast majority of her peers, Koller dedicated herself to artistic study and exhibiting. Her works were shown at important exhibits in Vienna, Munich, Leipzig and at the Woman’s Building in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. At the age of 33, Koller married the Catholic physician Hugo Koller, with whom she returned to live in Vienna in 1903. Neither her marriage, nor the birth of a daughter and son, stopped her from continuing her artistic career. Koller joined the Association of Austrian Women Artists in 1910 to argue for women’s integration into the art world.

If Koller could not officially join the Secession, she nevertheless was an astute practitioner of the style practiced by the foremost artists in Vienna at the time (often referred to as Viennese Modernism). The flatness of Sitting, where the top two-thirds of the painting looks as flat as a postcard, along with its delicate asymmetries, were common features of the avant-garde in Vienna. The play of gold against white is seen not only in works like Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze of 1902, but also in the architecture of leading Viennese figures such as Joseph Maria Olbrich and Otto Wagner. But in a number of ways, Koller’s work is more radical and more of a departure from nineteenth-century precedents. In comparison to Klimt’s Gold Period works, or even the ornamental bands of gold swirls that frame Stonborogh’s face, Koller restricts the gold to a small square behind Marietta’s head, relying more on abstraction. Her painting eschews the decorative charm of women’s fashion, seen in the works of Klimt and Whistler. And while Klimt and many of his contemporaries continue to paint women in mythological and allegorical guise, Marietta is clearly a contemporary model in a studio.

Woman as vision / invisible women

By the early 1930s, Broncia Koller’s career was lost to art history. Despite her extraordinary artistic talent and insight, like so many of her fellow women artists in early twentieth-century Europe, Koller’s work and career would come to be almost completely erased; an art critic in the 1930s would refer to her as “the talented wife of a prominent husband.” Her role at the center of Vienna’s elite social circles led some to see her as a dilettante rather than a brilliant interpreter of the Secession aesthetic. The year of her death, 1934, saw the rise of fascism and increasing antisemitism. Had she lived to see the Anschluss—the annexation of Austria by the Nazis in 1938—Koller, like many of her Jewish colleagues, would have been subjected to hatred and violence, and later deportation and murder. She was gone by then but her children, half-Jewish, had a precarious existence in Vienna until the end of the war.

Koller’s work fell into obscurity and only in 1961 was her art once again exhibited, thanks to the efforts of her daughter, Sylvia. It took until 1980 before she received a one-person exhibit in a museum. Only during the past decade, along with other women artists from early 20th-century Vienna, has Koller become better known, rather than a marginal figure on the fringes of the (male) Viennese Secession. Her early success, followed by the near demise of her public visibility, reminds us that both canons of art history, and attitudes towards gender fluctuate with historical forces and currents.