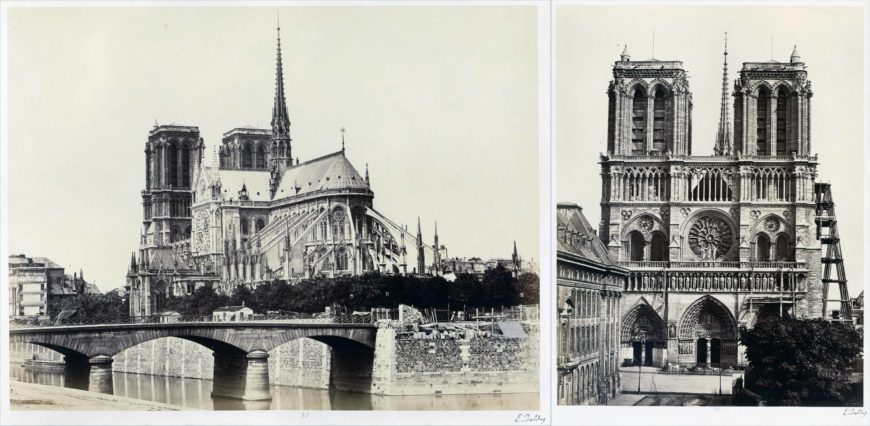

Edouard Baldus, Notre-Dame, abside (left) and façade (right), 1860s, albumen silver print from glass negative, left: 21.7 x 28.6 cm, right: 27.6 x 21.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

After hoards of angry mobs and French Revolutionaries looted structures such as the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris for being symbols of the power and monarchy of France, the government became acutely aware of the vulnerability of the country’s irreplaceable historic buildings. The widespread fear of losing even more touchstones to an enduring, shared past after three revolutions promoted a public- and government-supported veneration for monuments and French history, and a desire to preserve or commemorate history. The Mission Héliographique, established by France’s Historic Monuments Commission in 1851, was a project with a lofty goal: to use photography to provide an accurate, unifying, historically rooted sense of national identity that simultaneously conveyed “the permanence of the past, the viability of the future, or a sweet marriage of the two in the present . . . equivalent incidents in an optical voyage into the enterprise that was modern France.” [1]

A government-sponsored photography project

The Mission Héliographique was the earliest known large-scale government-sponsored photography project, and it was formed a little over a decade after the public announcement of the invention of the medium in 1839. Perhaps understandably, photography’s processes evolved as the members of the Mission worked, and they frequently adapted to new modes of making images.

Édouard Baldus, Arles, Amphithéâtre, 1851, salted paper print from paper negative, 44.8 x 50.2 cm (© Ministère de la Culture (France), Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, Diffusion RMN-GP)

Among the photographers hired by the Mission Héliographique was the German-born Édouard Baldus, a painter who only had taken up photography a couple of years earlier. Nevertheless, Baldus quickly established himself as a noteworthy architectural photographer with the Mission Héliographique, and this work helped him get hired for other later government projects, too. [2] For the Mission, Baldus was assigned a territory south and east of Paris, which included photographing monuments and structures at Fontainebleau, Lyon, the Rhône valley, and Provençe, including Arles—a town that about four decades later would become the home to painter Vincent van Gogh.

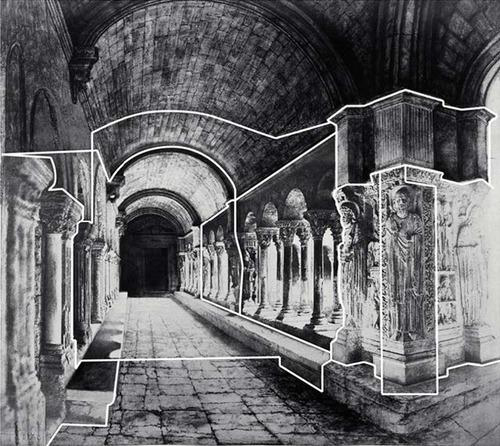

Édouard Baldus, Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles, 1851, salted paper print from paper negatives, with applied media, 17 5/8 x 19 3/4 inches (© Ministère de la Culture (France), Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, Diffusion RMN-GP)

Baldus in Arles

While Baldus was in Arles to photograph its ancient Roman amphitheater, he visited the medieval cloister of the church of Saint-Trophime (constructed from 1165–80 C.E.). [3] As he stood at the corner of the cloister’s gallery, feeling the smooth stone blocks of brick worn by centuries of monks’ footsteps, he undoubtedly sized up the substantial photographic challenge of capturing the multiple detailed figurative carvings, barrel-vaulted ceiling, decorative columns, and carved capitals with detail—despite their strong back-lighting from the cloister garden. Nevertheless, as Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Malcolm R. Daniel noted, Baldus wanted to make this photograph for several reasons. Not only was the cloister under consideration for national contribution to a restoration project, but the structure also was a site commonly represented in prints, and had become synonymous with French history and nationhood:

Here, indeed, was a scene worthy of representation: a physical space of arresting appearance; the type of site that might have been romantically depicted by earlier lithographers; a part of the national patrimony, the protection and restoration of which might later be discussed by a circle of architects and historians gathered around the careful photographic documentation Baldus hoped to make. Malcolm R. Daniel [4]

Édouard Baldus, Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles, with Joins Between Negatives Marked in White Lines, 1851. Musée National des Monuments Francais, Paris.

To create the “impossible photograph” (the one illustrated at the top of this page)— that did not appear to have been overtly manipulated, yet revealed well-illuminated views of all of the ornate detailed carvings and other architectural details, Baldus took at least a dozen photographs of the cloister under different lighting conditions. He cut, pasted, and collaged together fragments from ten different paper negatives, carefully adjoining them along the meeting points of contours of cornices, columns, or masonry joins. When photography’s exposures still failed to reveal a satisfactory degree of surface detail in shadowy areas, Baldus took his paintbrushes and ink and painted-in sections. The ceiling, which appears to be a photograph, was one of his painted additions. (All of the ceiling exposures were washed over in shadow by the photographic process, and Baldus declared them unusable.) He also retouched edges, clarified details, and created more tonal contrasts with ink. The end result is a photographic image that accurately represents the scene’s architectural details—but one that would never have appeared to a viewer in that space.

Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles, thus exemplified what Jules-Claude Ziegler—one of Baldus’s contemporaries and a fellow “painter-photographer”—called a unique artistic sensibility shared by artists with skills in both media:

The choice of viewpoint, of the precise hour when that subject will have the best light, the pose of the model, the determination of the shadows of a statue—all demand the eye and sensibility of the artist. . . . [In these elements] one can easily recognize a print made by a man who is practiced in the fine arts or who is naturally talented. Jules-Claude Ziegler [5]

It also reflects Baldus’s unique experimental approach to the medium. In addition to collaging hand-made imagery into his photographs, he moved freely between the paper-based calotype process, printing on albumen paper, and the wet-plate collodion processes if he felt it would help him achieve the best image.

Oscar Gustave Rejlander, The Two Ways of Life, 1857, albumen print, 10.5 x 19.7 cm (Princeton University Art Museum)

Constructing nationhood

Not only is Baldus’s Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles an early example of the technical mastery of the paper-based calotype process, but it is one of the earliest manipulated photographs involving multiple negatives and painting. His work predates the constructed scenes of later “painter-photographers” including the Swedish-born English photographer Oscar Rejlander (whose The Two Ways of Life, 1857, was a montage of 32 collodion glass negatives in a single albumen print); Frenchman Gustave Le Gray (whose Grande Lame – Mediterranee – No. 19, 1857 included different sea and sky scenes, joined at the horizon); and Englishman Henry Peach Robinson (whose Fading Away, 1858, was an albumen photograph made from five collodion glass negatives). Like Baldus’s Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles, these images all approach the making of the photograph as a construction—an image in which the desired visual expression matches the scene imagined in the mind’s eye—rather than the one visible through the lens.

Édouard Baldus, Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles, 1851, salted paper print from paper negatives, with applied media, 17 5/8 x 19 3/4 inches (© Ministère de la Culture (France), Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, Diffusion RMN-GP)

Such an approach to Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles, however, is perhaps fitting to the task of the Mission Héliographique project, which sought to reunite a fractured patchwork of populations across the country of France as a central and cohesive nation with a shared history. The Mission’s desired construction of nationhood, then, proves no different from the idealism of Baldus’s Cloister of St. Trophîme, Arles: both aspired to use photography to make an imagined reality visible, tangible, and therefore achievable.