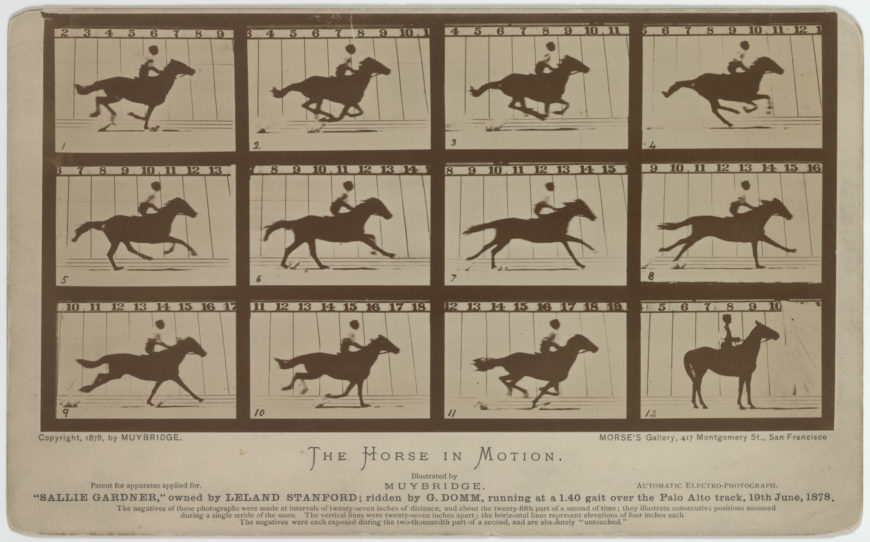

Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion (“Sallie Gardner,” Owned by Leland Stanford; Running at a 1:40 Gait Over the Palo Alto Track, 19th June 1878), 1878, albumen print (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Until the 1870s, the prevailing convention in the visual arts for representing horses in mid-stride was the “flying gallop.” This graceful pose—in which the horse has all limbs straightened and extended to the end of their reach—was popularized in mass visual culture and in paintings such as Théodore Géricault’s Derby at Epsom.

Horse aficionados, including former California Governor/railroad company president/racehorse breeder Leland Stanford, speculated that there were indeed moments in a horse’s stride in which all hooves were off the ground and the animal enjoyed “unsupported transit.” [1] But he had no means to prove his theory, because the speed of a horse’s movement surpassed the sensitivity of his unaided eyesight, and photography’s shutter speeds just over three decades after the medium’s invention were not yet quick enough to capture such short slices of time.

Eadweard Muybridge, Mirror Lake, Valley of the Yosemite, 1872, albumen silver print from glass negative, 42.8 x 54.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In 1872, Stanford thought of photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who previously photographed Stanford’s opulent Sacramento home. Muybridge had been roaming the western United States in his one-horse carriage (equipped with a darkroom) to make photographs of majestic scenes such as the Yosemite Valley for his commercial studio Helios. He agreed in 1872 to work for Stanford at his Palo Alto Stock Farm to improve photographic shutter speeds and ultimately help determine whether all four feet of a horse are off the ground at any point in mid-gallop.

The irascible Muybridge (born Edward James Muggeridge) had to temporarily disband his motion-study work after shooting and killing Harry Larkyns, his wife’s lover, in 1874. Muybridge was jailed and tried for murder the following year, but was acquitted on the grounds of “justifiable homicide.” [2] Muybridge blamed a severe head injury suffered in a stagecoach accident in 1860 for his erratic actions.

Muybridge’s Palo Alto experiments

He would not return to work for Stanford until 1877, but Muybridge’s experiments quickly bore fruit. After experimenting with different camera systems, Muybridge made a series of photographs at Stanford’s Palo Alto track on June 19, 1878. The Horse in Motion: ‘Sallie Gardner,’ Owned by Leland Stanford: Running at a 140 Gait over the Palo Alto Track, 19th June, 1878, depicts horse “Sallie Gardner” in silhouette against a white grid marked by consecutively numbered segments of uniform size. As she ran at a speed of about forty miles per hour past Muybridge’s battery of twelve cameras equipped with stereoscopic lenses, she tripped threads to release their shutters for a duration of about 1/1,000th of a second.

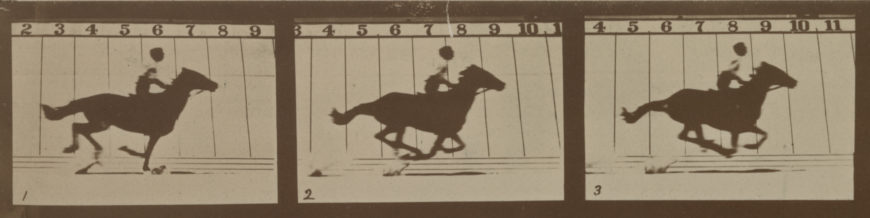

First three images of Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion (“Sallie Gardner,” Owned by Leland Stanford; Running at a 1:40 Gait Over the Palo Alto Track, 19th June 1878), 1878, albumen print (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Muybridge’s set of photographs proved Stanford’s hypothesis of “unsupported transit”—that there indeed are moments during a horse’s stride when all four of its hooves are off the ground. His images also revealed that horses, assumed to be elegant and graceful (yet still powerful) creatures, moved awkwardly in mid-stride, with their limbs retracting and extending as one foot at a time contacts the ground. Photography’s ability to halt time’s passage and surpass unaided human vision was lauded as definitive proof of “unsupported transit,” and the “flying gallop” promptly disappeared from art and from illustrations in horse-racing periodicals. [3]

A closer look at ‘Sallie Gardner’s’ run

The title of Muybridge’s images implies that they show a narrative story of a horse in the act of running. They are “read” as most literary works are in the English language—in linear sequence, from top-to-bottom, left-to-right. Gaps of about a half-second in duration lie between each of Muybridge’s images, and imply elapsed unseen time, within which the horse’s body moved to the position we see in the next frame. Time’s passage is implied by changes in the spatial coordinates of Sallie’s body over time.

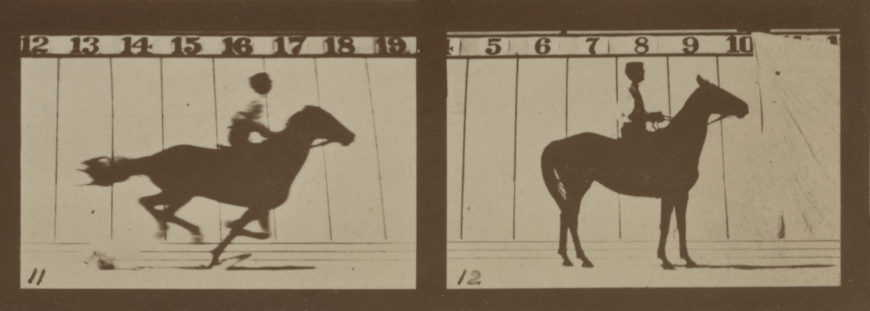

Last two images of Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion (“Sallie Gardner,” Owned by Leland Stanford; Running at a 1:40 Gait Over the Palo Alto Track, 19th June 1878), 1878, albumen print (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

However, Sallie’s run ends amazingly abruptly in the final image, which shows the horse standing still. In the twelfth photograph, numbers on the grid (beginning at 5) defy the previous sequential order (which ended at 19), and the estimated half-second interval between the other images no longer applies. Sallie would have accelerated to five times her speed, to about 200 miles per hour, between the last two frames. This is implausible for two reasons: first, horses can only run 45–50 miles per hour. And secondly, it would have been impossible for Sallie to come to an abrupt and complete stop so quickly.

Therefore, it is likely that Muybridge added this image from another sequence of photographs to end this series—and to indicate the completion of the act of running. Muybridge’s decision to insert a concluding image of Sallie at rest closes the series as a finished duration, as a “becoming” that finally “became,” and it provides the temporal completion of the physical act of the run. It was not unusual for Muybridge to splice-in images from other sequences to “close” his other series.[4]

‘Photographic truth’ vs. the unaided human eye

Muybridge’s photographs were immediately and enthusiastically published in magazines and newspapers worldwide. An article written by the editor of horse-racing magazine The Spirit of the Times hailed Muybridge’s photographs as “unerring,” while also pointing out that “it is difficult, to the verge of impossibility, to explain why what we see with our own eyes on the race-course differs so much from what we see on the plate of the photographer.”[5] Viewers trusted the photographs over their own vision. As photography historian Philip Prodger explained, during Muybridge’s time, the word “instantaneous” was “shorthand for authenticity and trustworthiness,” and was a synonym of “from life,” “from nature,” and of “naturalism.” [6] By the 1870s, photography’s use in the sciences helped establish the medium as a neutral means of capturing the accurate appearance of subjects in a full field of space, in a fraction of a second.

The unique “reality effects” of instantaneous photographs such as Muybridge’s sparked a heated discussion among artists, who debated whether the elegant horses in “flying gallop” poses were superior to the awkward equines of Muybridge’s photographs. French sculptor Auguste Rodin even thrust himself into the center of this debate, in a discussion about Muybridge’s instantaneous photography, by boldly declaring that “[i]t is the artist who is truthful, and it is the photograph that lies; for in reality time does not stop.” [7]

Muybridge himself perhaps provided the greatest challenge to Rodin’s words when, in 1879, he invented the zoopraxiscope. This hand-cranked device allowed a disc of sequential images to be passed by the eye in rapid succession. It is acknowledged as the precursor of the invention of cinema, and as a milestone in the re-animation of time, although Muybridge saw them as a way of proving the veracity of his motion studies. When the first eleven images of Sallie Gardner are seen in rapid succession at a speed of at least 24 frames per second, they allow us to re-experience her run.

A .gif of 1 to 11 of Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion (“Sallie Gardner,” Owned by Leland Stanford; Running at a 1:40 Gait Over the Palo Alto Track, 19th June 1878), 1878, albumen print (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)