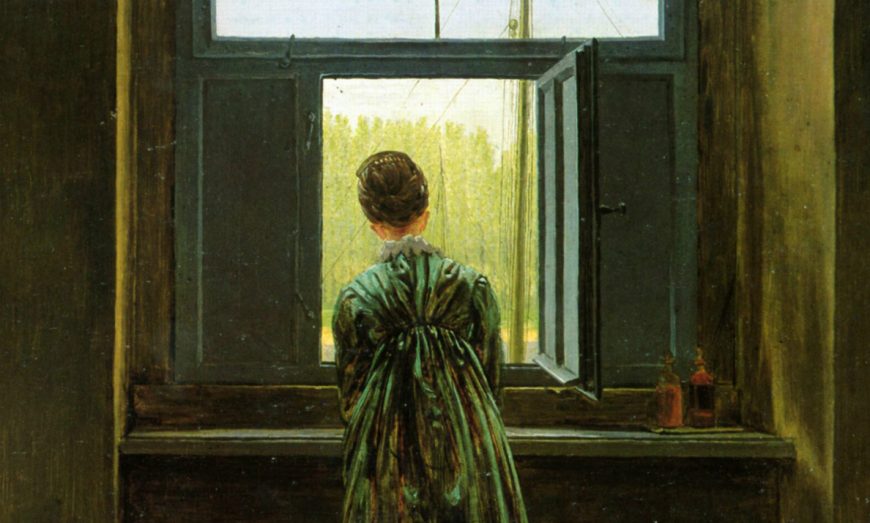

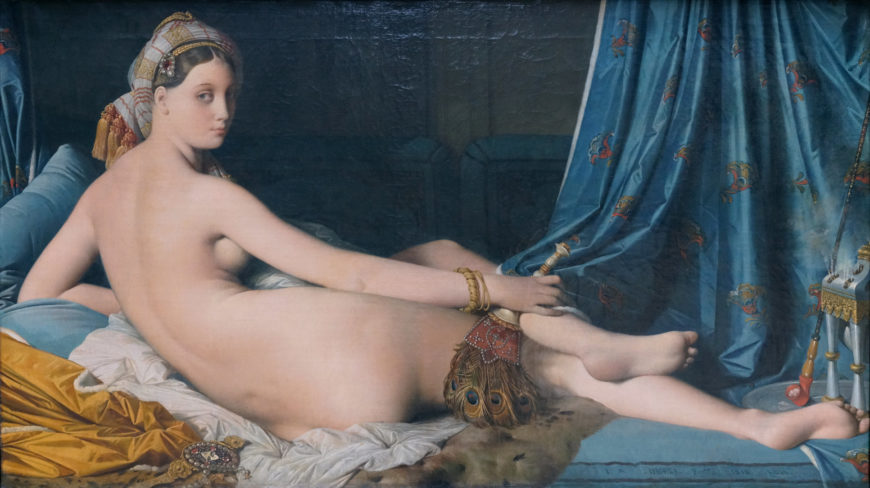

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, Oil on canvas, 36″ x 63″ (91 x 162 cm), (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the Louvre, looking at a painting by Ingres called the “Grande Odalisque.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:09] “Odalisque” simply means a woman in a harem.

Dr. Zucker: [0:11] But the Western conception of what a harem was, versus what a harem actually was, are two very different things.

Dr. Harris: [0:18] And Ingres never went to the Near East or North Africa, so this isn’t based on observation. This is entirely a Western fantasy.

Dr. Zucker: [0:26] What we’re seeing is this languid, nude woman, whose back is turned to us, and yet whose body is flexible enough for her head to turn back and look directly at us with a slightly coy eye.

Dr. Harris: [0:39] But also with a sense of reserve and distance. And so I think that’s one of the tensions here is this beautiful female, nude, but also the unavailability of her body and the slightly cold or distant gaze.

Dr. Zucker: [0:52] Also the coolness of the coloration and the perfection of the surface of the canvas. There is not a brushstroke to be seen. She seems unavailable because the hand of the artist is completely absent.

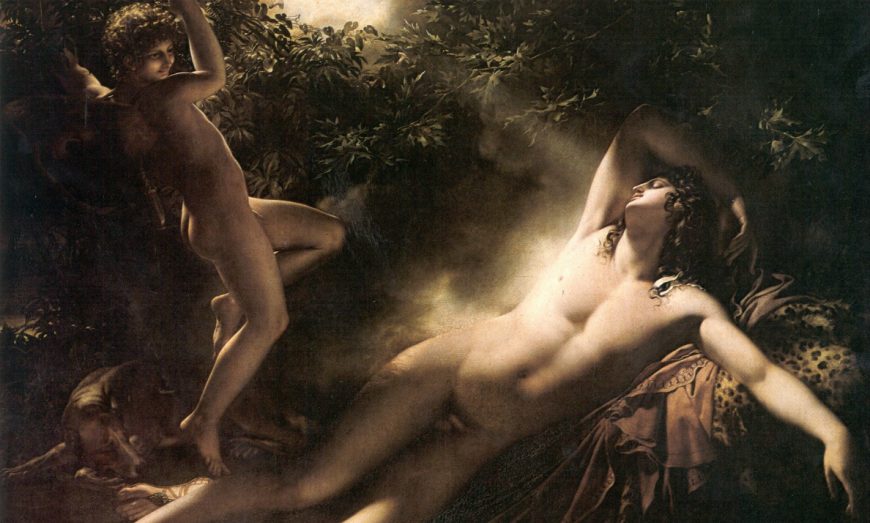

Dr. Harris: [1:04] Now, the subject of the female nude goes back to ancient Greece and ancient Rome, through the Renaissance with artists like Titian and Giorgione. But here in the 19th century in France, when artists painted the female nude, they continued that tradition of painting ancient Greek goddesses or mythological figures.

[1:23] It was important for the nude to be distanced. In other words, not a contemporary nude figure, but distanced by time, that classical figure.

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] This figure, however, is distanced by geography.

Dr. Harris: [1:35] It’s important to remember that Napoleon, only years before, was in North Africa and the Near East. And so although this was distant geographically to people in France, it was also exotic, and there was a real curiosity about these cultures.

Dr. Zucker: [1:51] Although we don’t see anything authentic here.

Dr. Harris: [1:54] Ingres emerges from this Neoclassical tradition of David.

Dr. Zucker: [1:58] He was David’s most famous student.

Dr. Harris: [2:01] Part of the lack of any visible brushstrokes, the emphasis on line and contour, these are all things that are part of that Neoclassical tradition.

Dr. Zucker: [2:10] He’s willing to distort the body much more than David ever was. In fact, her body seems impossible. Her back is simply too long, as if there are extra vertebrae. Her left leg, where would it attach to her thigh?

Dr. Harris: [2:23] Even her left calf is way too long, and one part doesn’t seem to attach to another. Yet, we don’t notice those things when we first approach this painting. Which speaks to Ingres’ goal, which was to create something that was ideal and beautiful, and that naturalism, that illusion of reality in terms of anatomy, wasn’t as important.

Dr. Zucker: [2:44] Don’t make the mistake that Ingres didn’t understand human anatomy. These were distortions that were quite purposeful.

Dr. Harris: [2:50] The nude is surrounded by this lush environment of embroidered satins, and silks, and jewels, and pearls, and that peacock-feather fan that brushes against her thigh. In a way, it seems to me that there’s a coolness about her, but a sensuality in her surroundings.

Dr. Zucker: [3:07] This is a painting that really is a tease. It is luxurious in every way, from the pipe on the right, to the satins, to the silkiness of her skin. And yet the figure and the location are completely unavailable to the viewer. She’s both present and absent, in a way.

Dr. Harris: [3:22] I’m noticing the way that that left elbow presses into that pillow, giving us a sense of the weight of her body, and that lovely turban and jewels around her head.

Dr. Zucker: [3:32] Look at the composition. Look at the way that the turn of her nose leads into her shoulder, runs down the curve of her right arm, and is picked up by the curtain that loops back up, creating a continuous inverse arc.

Dr. Harris: [3:44] It is those lovely shapes that make one forget about those anatomical inaccuracies. It is the ideal beauty that Ingres has presented us with here.

Dr. Zucker: [3:55] It’s because of that that this painting, and Ingres’ career in general, is often seen as a hinge between the Neoclassical and Romanticism.

[4:02] [music]

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A quick study

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Self-Portrait at age 24, oil on canvas, 61 x 77 cm (Château de Chantilly)

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was an artist of immense importance during the first half of the nineteenth century. His father, Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres was a decorative artist of only minor influence who instructed his young son in the basics of drawing by allowing him to copy the family’s extensive print collection that included reproductions from artists such as Boucher, Correggio, Raphael, and Rubens. In 1791, at just 11 years of age, Ingres the Younger began his formal artistic education at the Académie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture in Toulouse, just 35 miles from his hometown of Montauban.

Ingres was a quick study. In 1797—at the tender age of 16 years—he won the Académie’s first prize in drawing. Clearly destined for great things, Ingres packed his trunks less than six months later and moved to Paris to begin his instruction in the studio of Jacques-Louis David, the most strident representative of the Neoclassical style. David stressed to those he instructed the importance of drawing and studying from the nude model. In the years that followed, Ingres not only benefitted from David’s instruction—and the prestige and caché that such an honor bestowed—but also learned from many of David’s past students who frequented their former teacher’s studio. These artists comprise a “who’s who” of late-eighteenth-century French neoclassical art and include painters such as Jean-Germain Droais, Anne-Louis Girodet, and Antoine Jean-Gros.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the Tent of Achilles, oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 57 1/2″ (École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris)

The Rome Prize—a bright future

The Prix de Rome—the Rome Prize—was the most prestigious fellowship that the French government awarded to a student at the Paris École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts), the leading art school in France from its founding in 1663 until it was finally dissolved in 1968. The recipient of the Prix de Rome was provided with a living stipend, studio space at the French Academy in Rome, and the opportunity to immerse themselves in Rome’s classical ruins and the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters. It promised to be a great five years for any aspiring artist. Joseph-Marie Vien, David’s own teacher, had won the award in 1743. David won the award in 1774—after four unsuccessful attempts. Ingres was formally admitted to the painting department of the École des Beaux-Arts in October 1799. The following year—in only his first attempt—Ingres tied for second place. In 1801, his painting of The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the Tent of Achilles won him the Prix de Rome. He turned 21 years old that August. Ingres had a bright future indeed.

Hierarchy of subjects

The Prix de Rome—to say nothing of the instruction Ingres received within David’s studio and at the École des Beaux-Arts—reinforced the hierarchy of the subjects of painting that had been a foundational element of French art instruction for more than a century. Artists with the greatest skill aspired to complete grand manner history paintings. These were immense compositions often depicting narratives from the classical past or from the Jewish and Christian Bibles. In addition to being large—and expensive—these works allowed the most accomplished and intellectually engaged artists to provide the art-viewing public with an important moral message—an exemplum virtutis (an example of virtue). David’s 1784 masterwork Oath of the Horatii is one such example.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Valpinçon Bather, 1808. oil on canvas, 57 x 38.4 cm (Louvre, Paris)

The nude (and not the classical past)

Due to the financial woes of the French government in the first years of the nineteenth century, Ingres’s Prix de Rome—which he won in 1801—was delayed until 1806. Two years later, Ingres sent to the École three compositions—intended to demonstrate his artistic growth while studying at the French Academy in Rome. Interestingly, all three of these works—The Valpinçon Bather, the so-called Sleeper of Naples, and Oedipus and the Sphinx—depict elements of the female nude (to be fair, however, the sphinx is not human). The first two, however, do not depict a story from the classical past. Instead, nearly the entire focus of each composition is on the female form. While Ingres has retained the formal elements that were so much a part of his neoclassical training—extreme linearity and a cool, “licked’ surface” (where brushwork is nearly invisible)—he had begun to reject neoclassical subject matter and the idea that art should be morally instructive. Indeed, by 1808, Ingres was beginning to walk on both sides of the neoclassical/romantic divide. In few works is a Neoclassical style fused with a romantic subject matter more clearly than in Ingres’s 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque.

Ingres completed his time at the French Academy in Rome in 1810. Rather than immediately return to Paris however, he remained in the Eternal City and completed several large-scale history paintings. In 1814 he traveled to Naples and was employed by Caroline Murat, the Queen of Naples (who also happened to be Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister). She commissioned La Grande Odalisque, a composition that was intended to be a pendant to his earlier composition, Sleeper of Naples.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

At first glance, Ingres’s subject matter is of the most traditional sort. Certainly, the reclining female nude had been a common subject matter for centuries. Ingres was working within a visual tradition that included artists such as Giorgione (Sleeping Venus, 1510), Titian (Venus of Urbino, 1538) and Velazquez (Rokeby Venus, 1647-51). But the titles for all three of those paintings have one word in common: Venus. Indeed, it was common to cloak paintings of the female nude in the disguise of classical mythology.

Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510, oil on canvas, 108.5 x 175 cm (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden)

Ingres (and Goya, who was working within a similar vein with his La Maja Desnuda—see below) refused to disguise who and what his female figure was. She was not the Roman goddess of love and beauty. Instead, she was an odalisque, a concubine who lived in a harem and existed for the sexual pleasure of the sultan.

Francisco Goya, La maja desnuda (Naked Maja), c. 1797–1800, oil on canvas, 98 x 191 cm (Prado, Madrid)

In his painting La Grande Odalisque (below), Ingres transports the viewer to the Orient, a far-away land for a Parisian audience in the second decade of the nineteenth century (in this context, “Orient” means Near East more so than the Far East). The woman—who wears nothing other than jewelry and a turban—lies on a divan, her back to the viewer. She seemingly peeks over her shoulder, as if to look at someone who has just entered her room, a space that is luxuriously appointed with fine damask and satin fabrics. She wears what appears to be a ruby and pearl encrusted broach in her hair and a gold bracelet on her right wrist. In her right hand she holds a peacock fan, another symbol of affluence, and another piece of metalwork—a facedown bejeweled mirror, perhaps?—can be seen along the lower left edge of the painting.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Along the right side of the composition we see a hookah, a kind of pipe that was used for smoking tobacco, hashish and opium. All of these Oriental elements—fabric, turban, fan, hookah—did the same thing for Ingres’s odalisque as Titian’s Venetian courtesan being labeled “Venus”—that is, it provided a distance that allowed the (male) viewer to safely gaze at the female nude who primarily existed for his enjoyment.

Hookah (detail), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

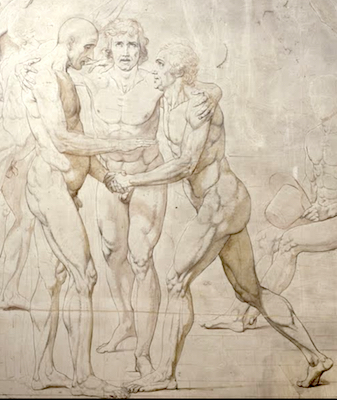

Jacques Louis David, The Jeu de Paume Oath (or Oath of the Tennis Court), 1790–92, pen, ink, wash, and white highlights on pencil strokes, 660 x 400 cm (Palace of Versailles)

And what a nude it is. When glancing at the painting, one can immediately see the linearity that was so important to David in particular, and the French neoclassical style more broadly. But when looking at the odalisque’s body, the same viewer can also immediately notice how far Ingres has strayed from David’s particular style of rendering the human form—look for instance at her elongated back and right arm. David was largely interest in idealizing the human body, rendering it not as it existed, but as he wished it did, in an anatomically perfect state. David’s commitment to the idealizing the human form can clearly be seen in his preparatory drawings for his never completed Oath of the Tennis Court(left). There can be no doubt that this is how David taught Ingres to render the body.

Students often stray from their teacher’s instruction, however. In La Grande Odalisque, Ingres rendered the female body in an exaggerated, almost unbelievable way. Much like the Mannerists centuries earlier—Parmigianino’s Madonna of the Long Neck (c. 1535) immediately comes to mind—Ingres distorted the female form in order to make her body more sinuous and elegant. Her back seems to have two or three more vertebrae than are necessary, and it is anatomically unlikely that her lower left leg could meet with the knee in the middle of the painting, or that her left thigh attached to this knee could reach her hip. Clearly, this is not the female body as it really exists. It is the female body, perhaps, as Ingres wished it to be, at least for the composition of this painting. And in this regard, David and his student Ingres have attempted to achieve the same end—idealization of the human form—though each strove to do so in markedly different ways.

Torso (detail), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A brief comparison between teacher and student makes clear how far Ingres had strayed from the neoclassical path David had laid. In some ways, La Grande Odalisque is based upon David’s 1800 portrait of Madame Récamier.

Both images show a recumbent woman who peers over her shoulder to look at the viewer. David and Ingres utilize line in a similar way. However, David depicts Récamier at the height of neoclassical fashion, wearing an Empire waistline dress and an à la grecque hairstyle. One gets the sense that there is real a body underneath that dress. In contrast, Ingres’s odalisque is a naked “other” from the Orient, and no clothing could disguise the elongations and anatomical inaccuracies of her body. David remained a committed neoclassicist, while his former student retained his neoclassical line to embrace, in this case, a geographically distant and romantic subject. This tension between Neoclassicism and Romanticism will continue throughout the first half of the nineteenth century as painters will tend to side with either Ingres and his precise linearity or the painterly style of the younger painter Eugène Delacroix.