![David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives, c. 1845, salted paper print from paper [calotype] negative, 29.5 x 21.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/fish-wives-870x1168.jpg)

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives, c. 1845, salted paper print from paper [calotype] negative, 29.5 x 21.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

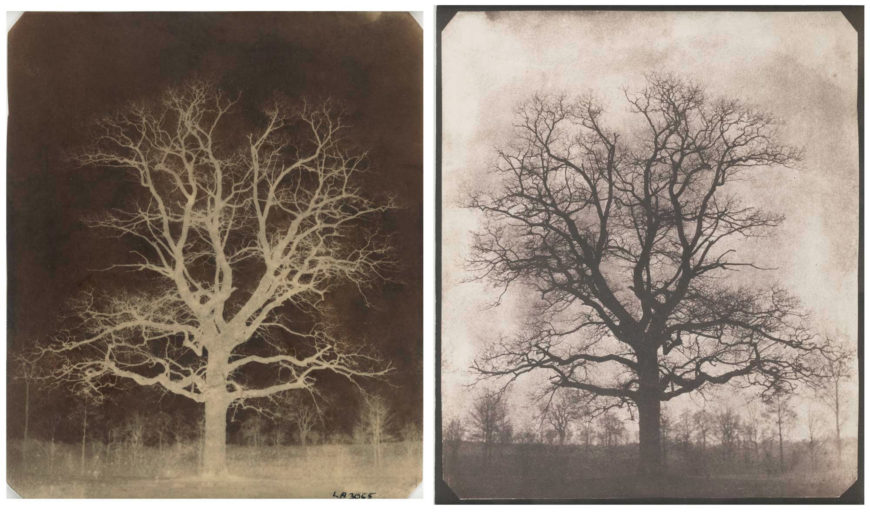

In one photograph, Newhaven Fishwives, two women are shown resting, one seated, one standing, against a nondescript outdoor background. They are shown in their traditional striped working dresses and white caps and may be taking a brief respite on their laborious, hilly, two-mile walk from Newhaven into the center of Edinburgh, carrying willow baskets filled with freshly caught fish. Carefully posed, their gazes averted, the women are not identifiable and thus they also reference the timeless trope of the picturesque fishwife. The expertly composed photograph makes clear the lofty aesthetic ambitions Hill and Adamson had for the new calotype process. Sometimes described as “Rembrandtesque,” the photograph is richly toned, with careful attention paid to contrasts of light and dark, as well as to the linear energy of the patterns on the dresses.

The calotype in Scotland

The calotype, the first paper-based photographic negative process, was invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1840. Talbot patented the process in 1841, which meant that those who wanted to experiment with the calotype would need to request his permission and pay a fee. The patent, much to the benefit of Hill and Adamson, did not apply to Scotland. Introduced in Scotland by Sir David Brewster, a scientist in St. Andrews, the calotype was taken up by his circle. Among them was Dr. John Adamson, who shared the process with his brother Robert. Brewster’s correspondence with Talbot provided a direct link between the inventor of the calotype and early experimenters.

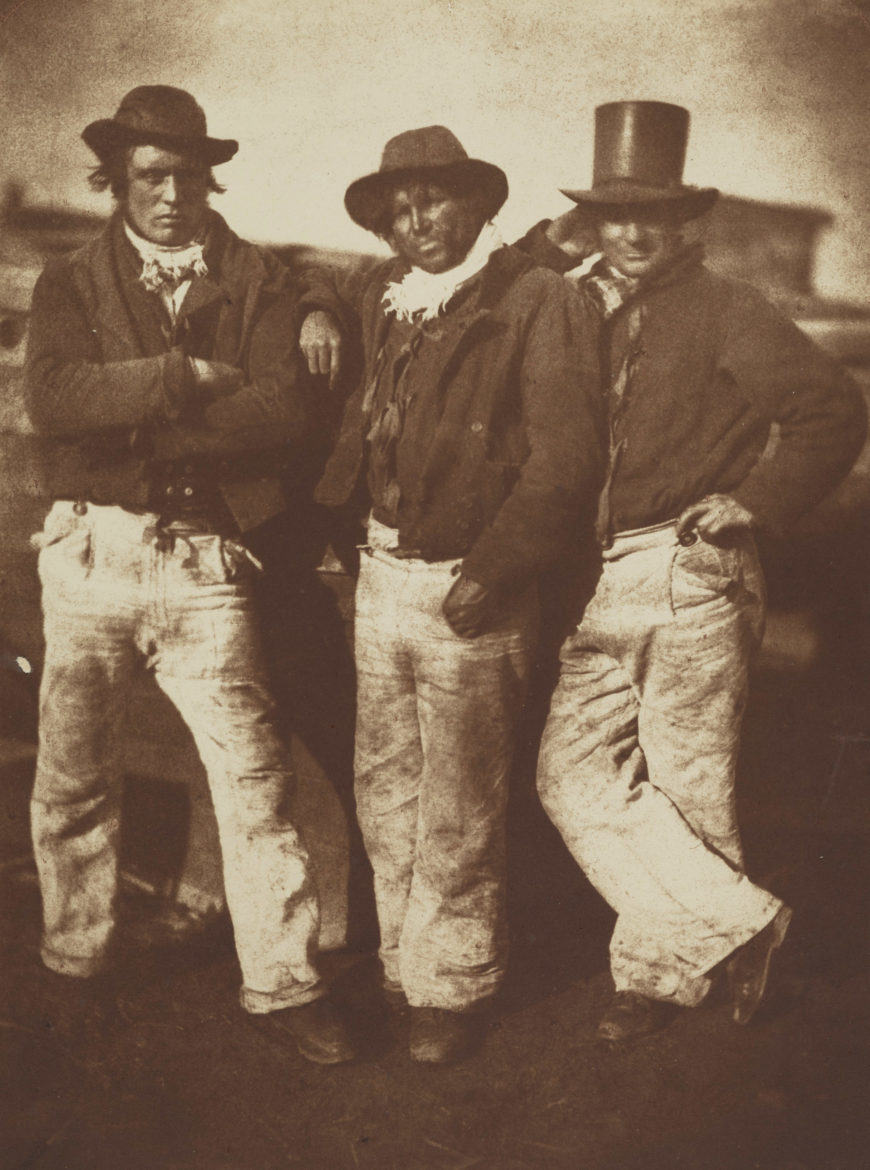

William Henry Fox Talbot, An Oak Tree in Winter, Lacock, c. 1842-43, calotype negative on waxed paper (left) and salted paper print (right) (British Library)

Unlike the sharp, detailed images produced by the daguerreotype, calotype images had a softened, almost hazy effect, such as we see in Talbot’s An Oak Tree in Winter. While the daguerreotype’s image revealed itself in crisp detail on the surface of the polished copper plate, the calotype’s image was nestled in the fibers of the paper, giving the calotype its characteristic softening effect. Although the image was not as sharp, the calotype had one distinct advantage over the daguerreotype: it was reproducible. It was also thought to be more closely aligned with art (rather than documentation), as described by Hill: “The rough and unequal texture throughout the paper is the main cause of the calotype failing in details before the Daguerreotype . . . and this is the very life of it. They look like the imperfect work of man . . . and not the much diminished perfect work of God.” [1] And indeed, the calotype (from the Greek word kalos, for beautiful) looked more like an etching or a drawing than the detailed images of the daguerreotype. It therefore lent itself to more picturesque subjects, and thus, to art.

The partnership

David Octavius Hill, The Disruption Assembly of 1843, 1843–66, oil on canvas, Free Presbytery Hall, The Mound, Edinburgh, 4′ 8″ x 12′

Robert Adamson was encouraged to open the first calotype studio in Edinburgh in 1843. Just a few weeks later, he began a partnership with David Octavius Hill, a landscape painter and member of the Royal Scottish Academy. Hill had committed to undertaking a large-scale painting commemorating the formation of the Free Church of Scotland, the so-called Disruption Painting. This required painting more than 400 individual portraits of the involved ministers. Hill initially came to Adamson with a proposal to photograph the ministers for his painting, which would be faster than drawing them by hand. The two men quickly found an easy working rapport and settled into what would be a brief, but incredibly productive, four-year partnership. Their studio specialized in portraits of prominent men and women, landscape and architectural views, and images of Scottish villages and their inhabitants.

Newhaven: a model community

Newhaven Fishwives was part of a series of photographs for a planned volume, The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth, which would feature images of those who lived and worked in the small fishing village of Newhaven. Although the album was never made, Hill and Adamson spent considerable time documenting the daily life and activity of the village, making upwards of 130 calotypes during their visits.

![David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives, c. 1845, salted paper print from paper [calotype] negative (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/DP140493-870x1191.jpg)

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives, c. 1845, salted paper print from paper [calotype] negative (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

![David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives, c. 1845, salted paper print from paper [calotype] negative, 29.5 x 21.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/fish-wives-870x1168.jpg)

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives, c. 1845, salted paper print from paper [calotype] negative, 29.5 x 21.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

There is another possible reason for their interest in Newhaven. The 1840s was a time of great social change and political unrest, as the results of the Industrial Revolution were being felt throughout Britain (and the rest of Europe). It has been suggested by scholars that the Newhaven photographs were Hill and Adamson’s contribution to the ongoing debate about concerns for the unemployed and urban poor. With slums emerging around Edinburgh, Newhaven was viewed by many as a model of a thriving working society that was entirely self-sustaining and still tied to its pre-industrial ways.

The photograph of the Newhaven Fishwives, which shows two industrious women in their working dress with the tools of their trade (the willow baskets used to carry fish), is exemplary of Hill and Adamson’s depictions of the Newhaven community as spiritual, literate, industrious, and self-sufficient. That they used the new technology of photography to picture this idyllic fishing village was perhaps ironic, but for Hill and Adamson it added to the work’s aesthetic appeal.

Pictorialist reappraisal

The Hill and Adamson partnership ended abruptly in 1847 with the premature death of Robert Adamson, but their work was given new relevance by the Pictorialists (1880s–1920s). In the early years of the 20th century, a series of photogravures of Hill and Adamson’s original images appeared in Alfred Stieglitz’s photography journal Camera Work.

Camera Work: Newhaven Fisheries, 1909, photogravure of Hill and Adamson, Newhaven Fisheries, c. 1845 (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

That Camera Work, the mouthpiece of the Pictorialist movement, would publish Hill and Adamson’s work should not come as a surprise. The journal and the man behind it were concerned, above all, with elevating the status of photography to the status of art by emulating the appearance and subjects of painting. The soft-focus, often picturesque subjects of Pictorialism found much-desired precedence in the work of Hill and Adamson, whose calotypes were similarly characterized by a softened focus, diminished details, and rich tones. For the Pictorialists, Hill and Adamson’s photographs were evidence that photography was more than mere documentation, that it was, and long had been, an art.