Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The colors of the walls are nearly as bright today as they were when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 C.E., burying the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale in Italy. [1] A rustic villa located just below the slopes of the volcano, it features some of the highest quality Roman wall paintings known to date. For nearly 2,000 years, the villa remained hidden under layers of ash and pumice stone until its rediscovery in 1900. The volcanic rich soil of ancient Boscoreale made it a desirable location for villas whose owners were engaged in agricultural activities. Nearly 30 of these villas, all of which were destroyed in the eruption, are known today. [2] A detailed plan of the villa can be found here.

Sleeping in the shadow of a volcano

When the villa was excavated, sixty-eight sections of wall paintings were removed before the remains of the villa were reburied. It was standard practice to reinter archeological sites that were discovered on privately owned land after excavating and removing anything of value. These painted panels were sold to museums around the world, often in pieces, but the wall paintings of Room M were purchased together and later reconstructed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1903. They provide the rare opportunity to study the frescoes of a room from this villa in their totality. This particular room is thought to have functioned as a cubiculum (pl. cubicula), a term used in the ancient Roman world to denote the most private rooms of a residence which mostly functioned as bedrooms.

The high-quality paintings in this room were created in the Second Pompeiian Style, which is known for its renderings of architectural features and illusionistic space. This style was especially popular in the mid-first century B.C.E. when this villa was constructed.

Left wall. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The frescoes of Room M

The wall paintings in Room M were created in the true fresco technique where the paint is applied directly to wet plaster allowing the color to penetrate the plaster and become a fixed part of the wall. Though the frescoes were already over a century old when the volcano erupted, this technique allowed them to retain their vibrant colors.

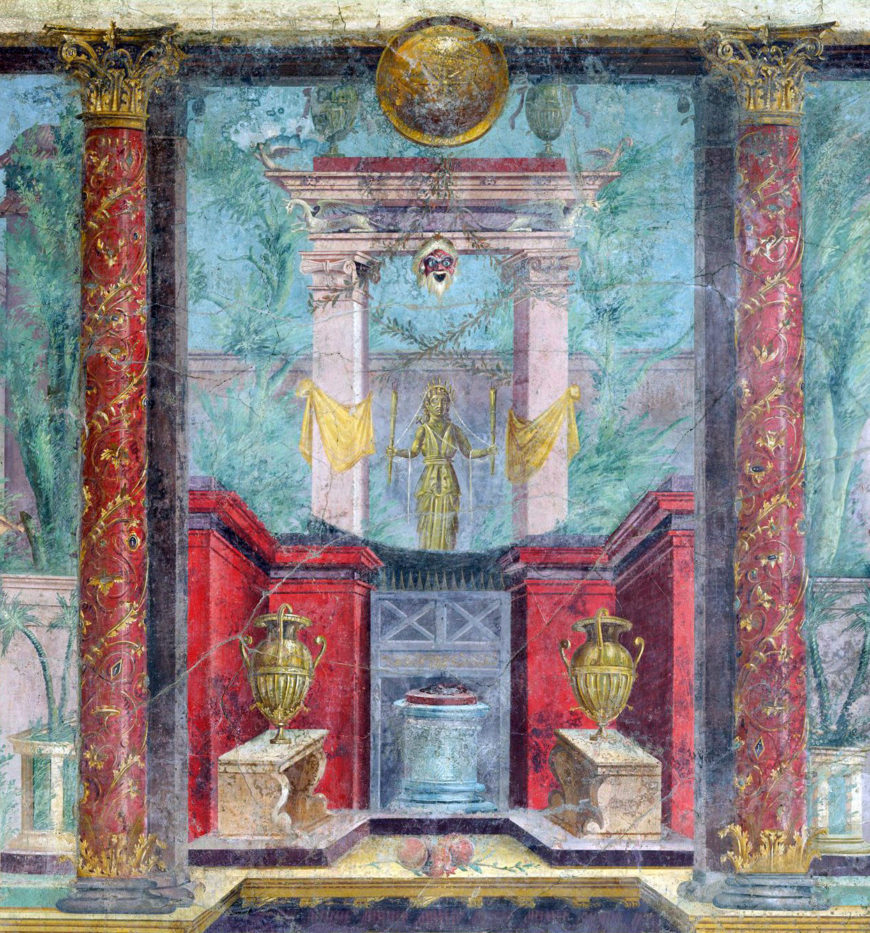

Painted corinthian pilasters (a squared column) support a painted architrave (horizontal beam) in each of the four corners of the room. The bottom of the walls feature painted blocks designed to replicate colored marble. Between these architectural elements are the painted scenes which make this room so notable. These scenes give the impression that the viewer has not walked into an enclosed bedroom, but rather could step outside into wondrous landscapes that are better than reality.

Right wall. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Each of the side walls, which are painted with the same types of views, are subdivided into four different sections, each separated by a (painted) column or pilaster. The painter visually opened the surface of the wall with idealized, colorful vistas. Though there are no windows on the side walls, these paintings illusionistically expand the space of the room and give the impression that fantastic landscapes lie just outside.

Detail of the left wall. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A room with a view

Upon entering the room, immediately to the left and right are the first of the architectural vistas: a town or cityscape. In the cityscape, buildings appear at different levels and recede into the background. These frescoes display one of the earliest uses of linear perspective adding to the impression of depth and distance portrayed in the scenes. The linear perspective used in the above panels features receding lines which converge at multiple points along the central vertical axis of the shrine panel. This technique was used by the ancient Roman painters to expand the apparent space of the walls. This differs from the one-point linear perspective developed in the Renaissance in which the lines converge into a single vanishing point.

Left wall with the large ornamental doorway, with figurative frieze above, and red balcony to the left, adorned with garlands and bucrania. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

These cityscapes appear four times throughout the frescoes, twice on each side wall. At the bottom of each cityscape, there is a large ornamental doorway, which invites the viewer into thinking that they could enter the city beyond. Painted friezes with miniature figures are found above the doorway in each of these four scenes. The painter paid great attention to detail when creating the doors, windows, and balconies, such as the small garlands that hang between ox skulls (bucrania) and which are attached to columns on one of the balconies.

Detail of a shrine with Ionic pilasters frames a statue holding a patera. Lavender cloth is tied around the pilasters. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

From city to shrine

Detail of the left wall showing a shrine with Ionic pilasters framing a statue holding torches. Gold cloth is tied around the pilasters. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

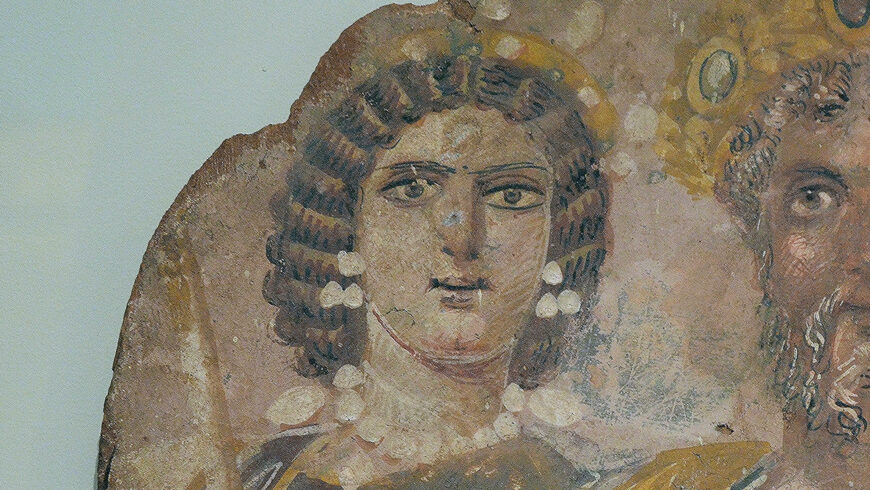

In between the cityscape panels are scenes of a shrine located within a sacred precinct. This scene is separated from the surrounding cityscapes by red columns encrusted with jewels and gilded plant tendrils and topped with golden Corinthian capitals. They appear to project forward into the space of the room even casting shadows, playing with the viewer’s perception of real versus painted space.

The shrine itself features two Ionic pilasters, recognizable from the volutes, or scrolls, in their capitals, supporting an entablature. On the left wall, a statue holds a torch in each hand, and on the right wall opposite, a statue holds a patera, a shallow bowl used during religious rites.

Cloths of gold (on the left wall) and lavender (on the right) are tied around the pilasters. The shrine is flanked on either side by trees with feathery foliage, heightening the impression of a outdoor shrine.

The shrine and statue are protected behind a red precinct wall, which again displays depth as it is painted as though receding further into space. To either side, in front of the wall, are benches, each with a golden vase atop it. In the center, an altar holds burning coals that emit smoke that rises into the air above. Offerings of fruit are placed in the foreground.

A Temple in a Courtyard

The final scene on each of the side walls is divided from the others by a single Corinthian pilaster with projecting squares, which would have marked the area of the room where the bed was in antiquity.

Grand propylon and temple. Detail of the right wall, showing a Corinthian pilaster with projecting squares on the right. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

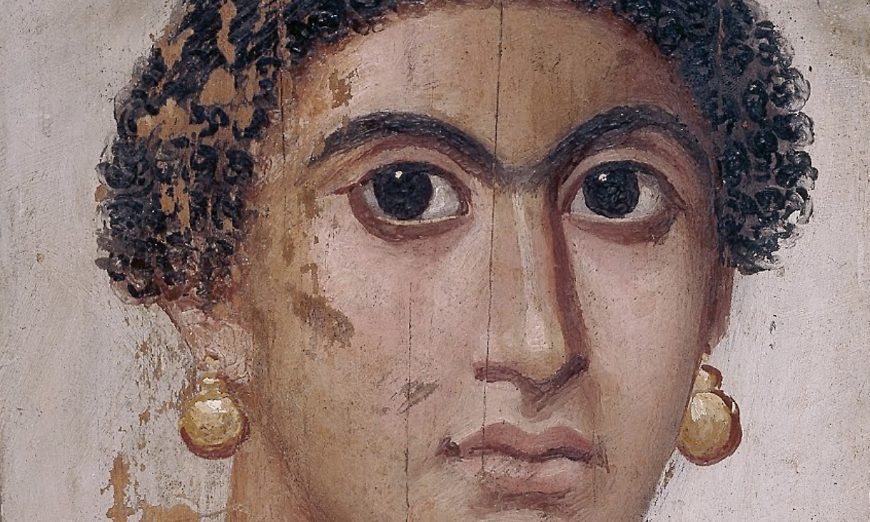

Here, the viewer is confronted with a grand propylon, or monumental columned entranceway, where golden Ionic columns support a triangular pediment. The pediment is broken in the middle to reveal a monopteral temple with red columns topped with gilded Corinthian capitals. The temple is surrounded by a rectangular portico with Tuscan columns that recedes into space.

Unlike with the cityscape, there is no doorway to invite the viewer to enter. The spaces between the columns of the propylon are blocked by high red walls to the left and right and a lower gray wall in the center flanked by Ionic pilasters that appear slightly closer to the viewer, and are topped with fruit and offerings. The artist also painted black curtains which are drawn back as if to reveal the temple and its portico to the viewer, inviting a peek inside this sacred space. A garland is draped over top of this curtain, though the garland itself differs on the left and right walls. In the foreground, centered between the propylon columns, is an altar topped with an incense burner.

These scenes, like that of the rustic shrines, are religious in nature, and support the illusion of an idealistic world that extends beyond the surface of the walls.

Rear wall. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The wall with the window

The rear wall of the bedroom also features duplicate scenes, though the real window cuts into the painted landscape. In the center of the wall are two more red and gold Corinthian columns.

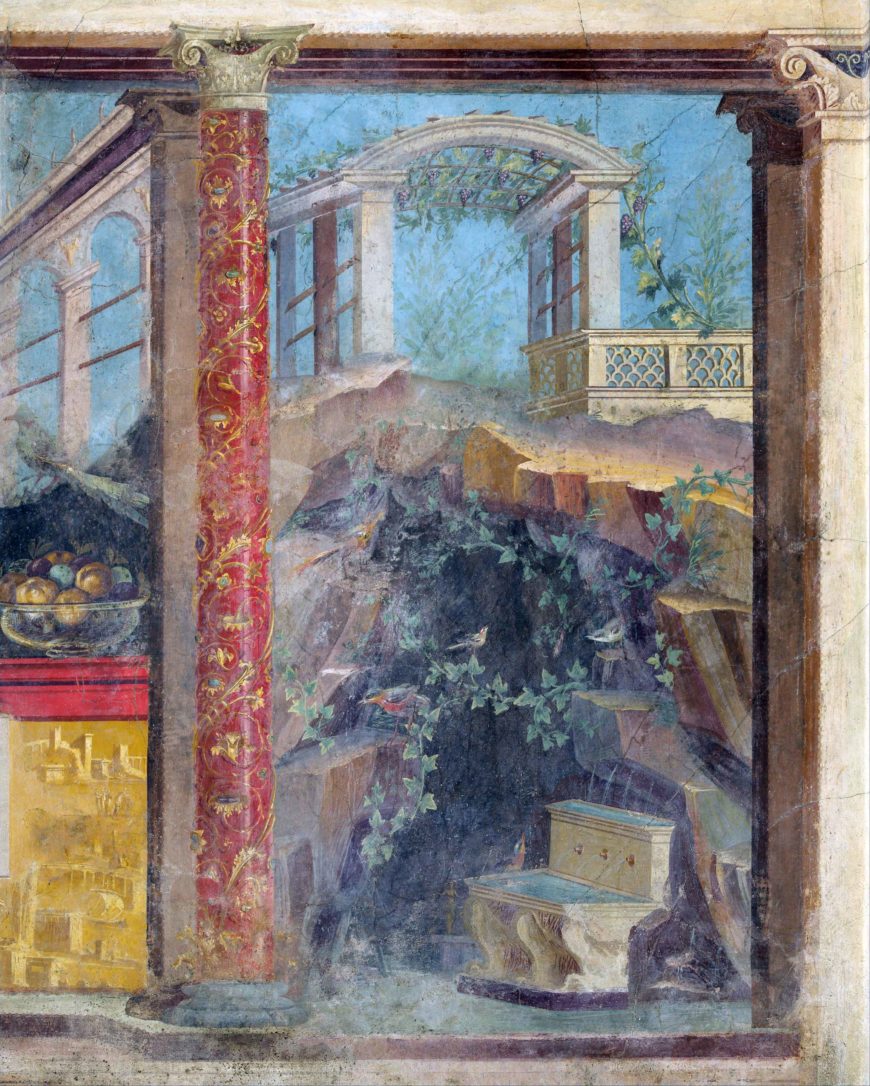

Detail of trellised arbor and cave. Rear wall, Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

To the left and right, the wall features rustic scenery. A trellised arbor entwined with grape vines is perched atop a rocky hill. Birds settle on rocks or vines or fly across this idyllic landscape. Below, there is a natural cave opening in front of which is an elegant man-made fountain. This combination of natural cave and water-features refers to a popular form of grotto often found attached to villas.

Detail of rear wall with yellow panel. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the center of the two columns is a yellow panel. The yellow panel is topped with a red architrave on which sits a translucent glass bowl overflowing with three-dimensional looking fruit. This landscape panel is painted monochromatically to suggest that it is an object like a marble relief as opposed to representing a “real” illusionistic space like the other portions of the fresco. Here, the painter used different shades of yellow and hatch marks to create texture, which, when looked at from a distance, allows one’s eye to perceive the subtle details of the scene. Within the painted panel there are figures crossing a bridge over water, fisherman in their boats, and buildings which recede into the background.

The window frame on the back wall was once wooden but is today filled with cement. The iron window grill came from elsewhere in the villa but was installed in the back wall before the fresco was sold. The twisted shape of the bars is a poignant reminder of the destruction caused by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

Detail of fruit bowl. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

All the world’s a stage

Detail of theatre mask and bronze shield. Right wall, Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E.

It is highly likely that the style of these illusionistic landscapes was based on the style of scenic painting, known as skenographia, used in Hellenistic theatre (as described by Roman architect Vitruvius). Styles and themes from Greek and Hellenistic art and culture often appear in Roman wall paintings, such as the Greek style theatre masks in the shapes of satyrs (the half-goat, half-man followers of the god Dionysus) hung in various places, to the round, bronze shields with their distinctive Macedonian star, the same type used by Alexander the Great, as seen in these frescoes.

Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Just as an audience could be visually transported to another location when watching a play, so too, could the owner of the villa as he admired the walls of his bedroom. These illusionistic vistas appear to dissolve the surface of the wall, allowing the viewer to marvel at this fanciful world as if through a window onto different scenes. It provided a symbolic escape where one could be visually transported to another location outside of the villa’s walls.

These vibrant frescoes blur the line between urban, rural, and sacred scenes as well as what is real and imaginary. Though today the villa is buried under mounds of dirt, still hidden from the world, the wall paintings of Room M continue to captivate viewers with their fantastical scenes.

Detail of the left wall, with a reconstructed capital on the right. Roman Frescoes from Room M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, c. 50–40 B.C.E., originally Boscoreale, reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Loss and conservation

In parts of the frescos you might notice short vertical brushstrokes that seem out of place with the rest of the painting. For example, this is evident when looking at one of the propylon column capitals on the left wall, part of the temple, and part of the sky. This difference is the result of conservation of this room.

The frescoes were damaged in the pyroclastic flows (waves of hot ash and gas which reached 750°F) and falling pumice stone in the eruption as well as due to its initial removal from the villa in the early 20th century. Some parts had become fragile, so the frescoes were cleaned and conserved by the museum between 2002 and 2007. Any sections that were missing paint were filled in the tratteggio manner, where the paint colors are similarly matched to the originals but are added in short vertical brushstrokes that can be distinguished from the original work upon closer examination. We are fortunate to still have this room despite the eruption and the room’s removal and transference across the globe.