Map of the Mediterranean with the findspot and production place of the Chigi Vase, c. 650 B.C.E. (underlying map © Google)

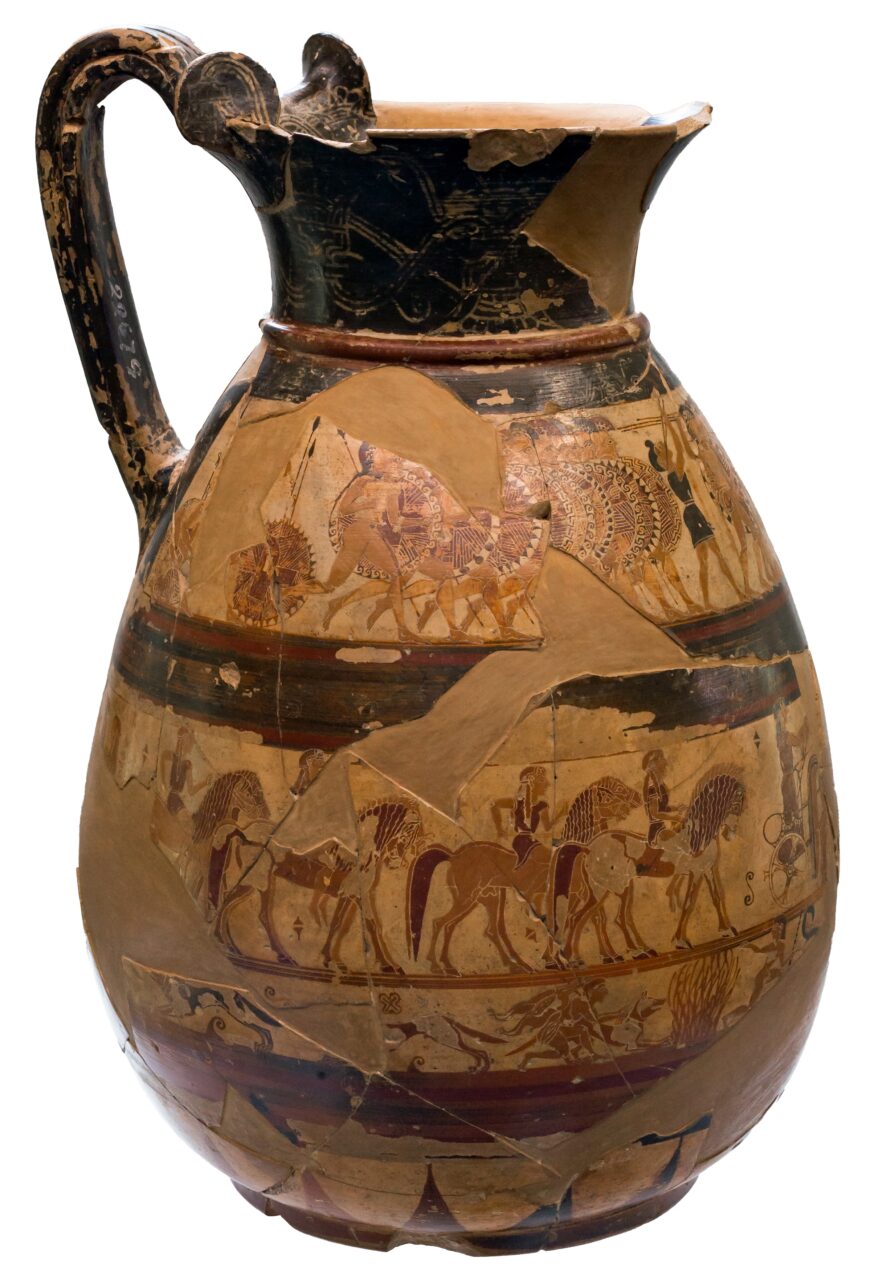

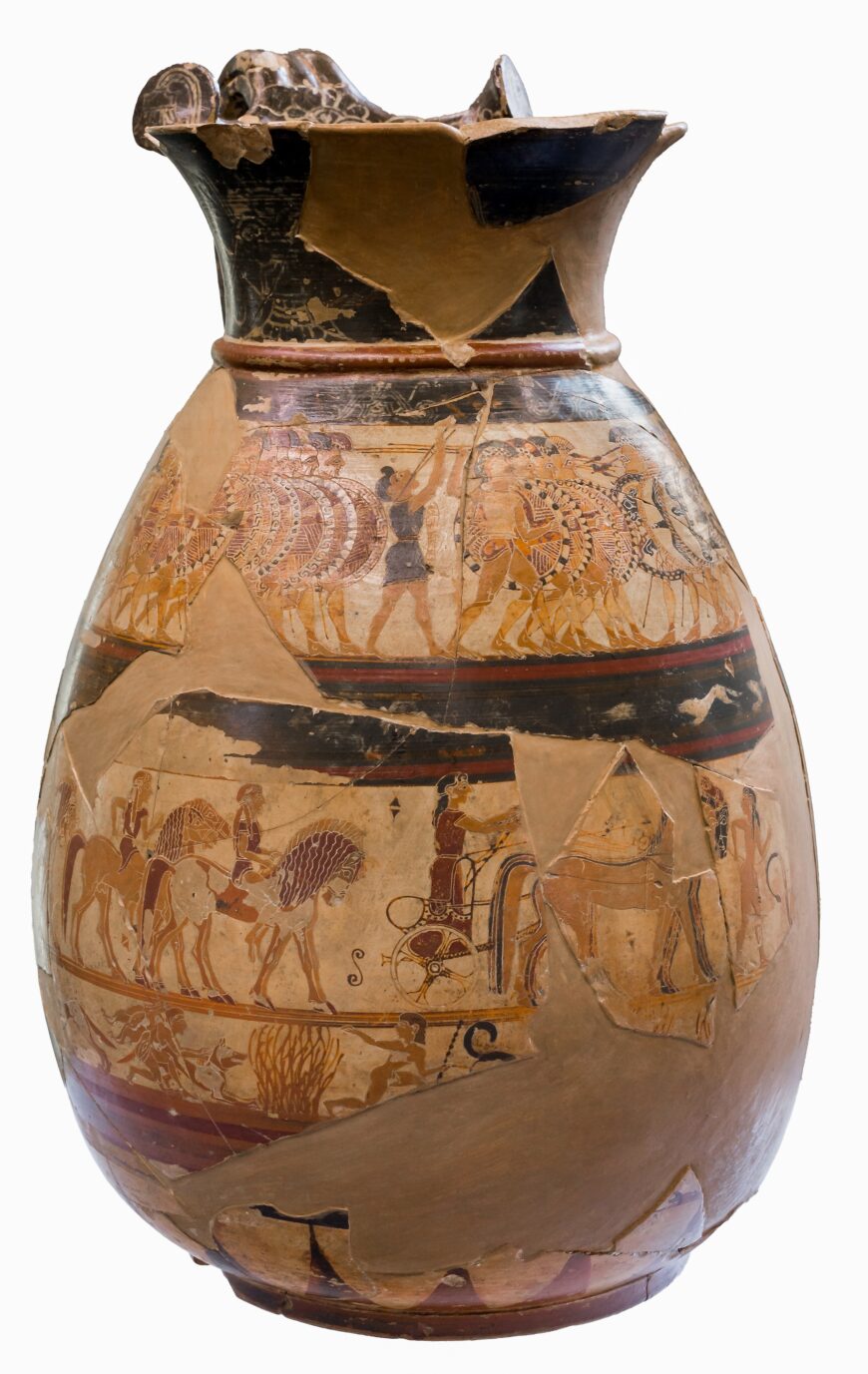

In 1881, workers discovered hundreds of fragments of ceramic vases while excavating an ancient tomb on the property of an Italian prince. In antiquity the tomb belonged to a rich Etruscan family, but the style and decoration of one fragmentary pitcher that was found within it suggested that it was made in the distant town of Corinth, in Greece. [1] The vessel is now known as the Chigi Vase, named after the prince who owned the land on which it was found. It traveled hundreds of miles (from Greece to Italy) before being buried with an Etruscan. But why would an Etruscan want a pot like this to accompany him into his grave? What did the pot do, who painted it, and what stories does it tell? The detailed decorations on the pitcher set it apart as one of the most elaborate vases that survives from the Protoarchaic period. The vase’s functionality, beauty, and narrative decorations made it attractive to its ancient Etruscan owner and still fascinate scholars today.

The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 26 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Corinthian origins

The Chigi Vase was found in modern day Italy, but its shape and decorative style suggest it was made in Corinth, Greece, and so we refer to it as Corinthian. It is a type of vessel known as an olpe. An olpe is a pitcher with a single vertical handle, an oval shaped body, and a wide opening at the top. In ancient Greece, olpai were probably used to pour wine, the beverage that fuelled communal gatherings. Corinthian craftspeople produced many olpai in the Protoarchaic period (c. 700–600 B.C.E.), and the Chigi Vase may have been the very first olpe made in that region. [2]

Although it is only 26 cm tall, the Chigi Vase is entirely covered in decorations organized into registers. The three main registers on the vase contain narrative scenes with human participants. To create the detailed images in these registers, the artist who painted the Chigi Vase used a decorative technique known as black-figure. He first painted the figures in silhouette, filling them in as solid shapes against the lighter background of the clay. He then added details to the figures by scratching into them (and the surface of the vase) with a thin, sharp tool, creating incised lines.

Lion in the lion hunt scene (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

If we look closely at the lion on the Chigi Vase, we can see that the painter used incisions to render the animal’s muscles and locks of hair. To make his images even more lively, the artisan added more color to them, as we see in the red paint that represents the bleeding wounds on the lion’s neck. This combination of silhouette figures further decorated with incision and added color is called the black-figure technique.

Corinthian vase-painters invented the black-figure technique around 650 B.C.E. and used it to decorate many of their vessels. However, the Chigi Vase is unlike many other black-figure vases because of its extensive polychromy. [3] The painter who decorated this olpe used bright yellow and red colors to paint his figures, rather than the black that we expect of the black-figure technique. This use of color reveals the painter’s interest in creating an extremely elaborate vase. In fact, the artist who made the Chigi Vase went so far as to decorate the black bands that encircle his vessel, which are often left plain on other Corinthian vases. On the Chigi Vase, these black bands were originally painted with white flowers and animals, though the white paint is now faded.

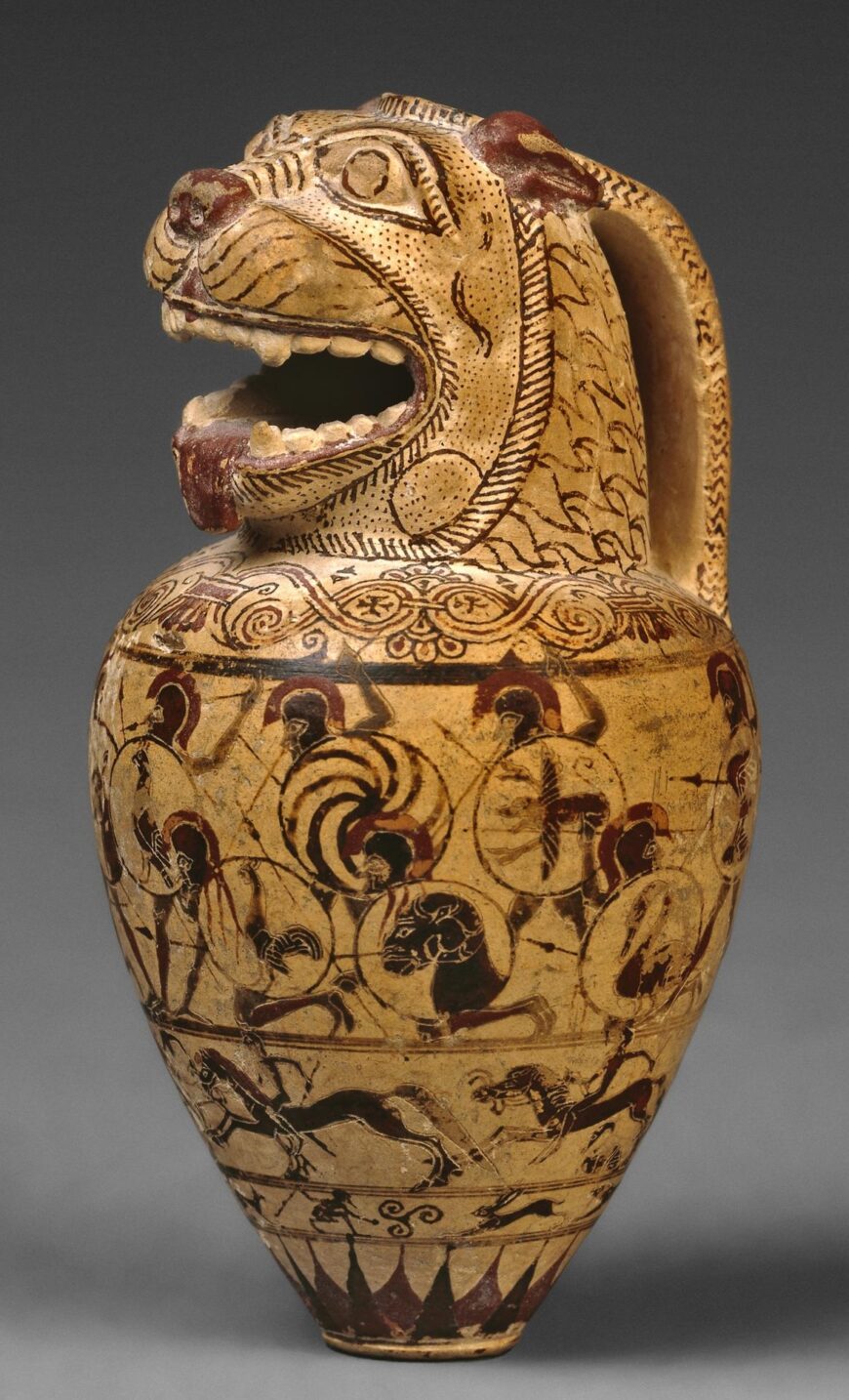

The Chigi Painter, The Macmillan aryballos, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 6.9 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

We do not know the real name of the artisan who created the Chigi Vase, but we call him the Chigi Painter after this olpe, his most famous work. Scholars believe that the Chigi Painter made several other vessels, including a small flask that is now in the British Museum. As on the Chigi Vase, the Chigi Painter decorated this vase in organized registers that he populated with energetic scenes painted using a colorful version of the black-figure technique. The Chigi Painter was one of the best artists working in Protoarchaic Corinth. His ability to create detailed, colorful images on tiny ceramic surfaces is unparalleled.

Hunts and battles: the stories on the Chigi Vase

The elaborate decorative style of the Chigi Vase is not the only thing that makes it special. Each of the vessel’s main registers tells at least one story that is easily recognizable and would have been meaningful to an ancient viewer. Before we consider how a Greek or Etruscan viewer might have interpreted the stories on this vase, we will look more closely at each of them.

Hare hunt with a young hunter hiding behind a bush with his dogs (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 2.2 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The bottom narrative register sits above several bands of decoration and depicts a hare hunt. Several boys, whose youth is made evident by their beardless faces, work together with their dogs to catch hares. One hunter, with two dead hares on his back, crouches and hides behind a bush and restrains his dog while another hunter (who stands on the other side of the bush) signals for him to stay hidden. [4]

Hare hunt with dogs chasing a hare (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 2.2 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Elsewhere in the same register, another youth hides behind a different bush, watching as his hounds run after a terrified hare who sprints towards him. Although this register is only partially preserved, it is full of movement and action. The hounds are painted in different colors, adding variety to the scene, and the landscape is indicated by the bushes scattered throughout.

The Judgment of Paris (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 4.6 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Three thin yellow lines separate the bottom and middle narrative registers. The middle register includes several different scenes. At the back, beneath the vase’s handle, is a depiction of the myth of the Judgment of Paris. The scene is now badly damaged, but scholars can tell what it depicts because the figures are labeled. [5] At the far left, we see Paris, here labeled Alexandros, another name for the same person. Paris faces three goddesses, though the heads of only two (Athena standing in front of Aphrodite) survive today. The scene shows the moment before Paris decides which of the three goddesses is the most beautiful. Although this representation of the famous myth does not make it clear whom Paris will choose, ancient viewers would be well aware that Paris would name Aphrodite as the most beautiful.

Lion hunt (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 4.6 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The figures in the Judgement of Paris scene do not interact with the other characters in the same register, who participate in different stories. One of these narratives appears just behind Paris. In contrast to the calm Judgment scene, which shows the moment before the central action of the story, this scene shows the climax of a gruesome lion hunt. Four young men attack a lion with spears. The three hunters closest to the lion have stabbed him in the haunch and neck, and blood streams from his wounds. The injured lion will likely die, but he has first managed to maul another young male hunter. As his victim tries to crawl away, the lion bites his torso, drawing blood. Such violent representations of lion hunts are unusual in Protoarchaic Greek art, but they were popular in Western Asia, and the Chigi Painter may have drawn inspiration from that region’s images while creating his own. [6] Lion hunts are metaphors for the dominance of civilized man over nature, though here, the nature symbolized by the lion has claimed a human victim.

Double-bodied sphinx (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 4.6 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

To the left of the lion scene, behind the last hunter who stabs the lion in the thigh, appears an unusual double-bodied sphinx that has two conjoined bodies and a single shared head. One of the sphinx’s two bodies is now largely missing, but its tail is still visible to the left of the break in the ceramic. In later Greek vase painting, sphinxes often hint at danger and impending death. [7] Perhaps this colorful sphinx is similarly signaling the demise of the young hunter who has been attacked by the lion to her left. With her two bodies and confrontational frontal face, she demands that we stop and look at her before continuing around the vase.

Chariot and horse riders with hare hunt below (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Just next to the sphinx is a chariot pulled by four horses who are directed by a nude youth. The chariot is followed by four young men riding horses. Each of these riders leads a second horse in addition to his own. Despite being separated from the lion hunt scene by the monstrous sphinx, we are probably meant to read these two scenes together: four of the five hunters who engage with the lion have just gotten off the horses that are led by their assistants, while the fifth has left his chariot to attack the feline. [8]

Chariot and double-bodied sphinx, with white animals on black register visible above (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The middle register and the top register are separated by a black band that was once decorated with white animals, including dogs chasing goats and hares. These figures are now barely visible, but we can see that they mostly run from right to left, mirroring the movement of the hare hunt in the bottom register.

Hoplite battle (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 5.2 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Musician in hoplite battle (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 5.2 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The top register shows a battle scene. At right, two groups of heavily armed soldiers rush forward to meet their opponents head on. They wear crested helmets with face coverings. They carry spears and shields with different decorations, including a gorgoneion, an eagle, and a lion, likely all protective emblems. [9]

The members of the opposing army are equipped with similar gear, though we see the inside of their shields rather than their exteriors because they carry them on their left arms and approach from the left. This group of soldiers is separated into two rows, between which walks a small musician who plays two pipes that are tightly strapped to his head. This young boy is probably playing music to rally the troops and keep them in pace. [10] Behind him, more soldiers approach the battle.

Hoplite battle (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 5.2 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The last soldiers in this group are still putting on their armor and rushing to join their companions, suggesting that they have been attacked by surprise. [11] To create an impression of depth in this battle scene, the Chigi Painter has overlapped the soldiers, painting each one partially over another to show the viewer that they are standing side by side. The closeness of the soldiers also reflects the chaos of battle. Although the fighting has not yet started, soon these men will meet in a noisy clash of armor and violence.

Hoplite battle (detail), The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 5.2 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This uppermost register of the Chigi Vase is especially important because it contains the earliest depiction of a new type of Greek warfare: the hoplite battle. Hoplite warfare became prevalent in Greece in the 8th century B.C.E. Hoplites are foot soldiers who wear heavy armor and carry shields. They fight side by side with their companions, lined up in tight ranks, using their shields to protect themselves and their comrades. To be successful in battle, hoplites had to be individually strong and collectively organized. [12] The Chigi Painter makes this clear in his miniature representation of hoplite warfare. Each hoplite on the Chigi Vase is equipped with his own armor, which he carries effortlessly, indicating his physical strength. In lockstep with his companions, shoulder to shoulder with his comrades, each soldier confronts his enemy.

Finding meaning on the Chigi Vase

Across three primary registers, the Chigi Painter decorated his olpe with a series of different scenes. Given the careful execution of these images, it seems unlikely that he chose his images accidentally. But how do these scenes relate to one another?

The Chigi Painter, The Chigi Vase, c. 640 B.C.E., ceramic, 26 cm high (Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Jeffrey Hurwit has proposed that the narratives on Chigi Vase can be read together, from bottom to top, as a depiction of the maturation of an elite Greek man. [13] In the lower register, boys practice their hunting skills in a low-stakes rural environment, chasing hares with their friends and their dogs. In the middle register, slightly older youths attack a more dangerous enemy (a lion) who has mauled one of their friends. They are supported by servants, who hold their horses as they fight. The Judgment of Paris scene on the back of this register might symbolize the difficulties young men encounter as they grow older and encounter women. The uppermost register shows the adult Greek man fulfilling his most important duty: fighting against enemies for the safety of his city-state, with the support of his hoplite comrades.

For a Greek viewer, this story of maturation would be meaningful. If a wealthy Greek man once owned the Chigi Vase, he might have been reminded of his own past as he looked at it. But what about the Etruscan who ended up putting the vase in his grave? Coming from a different place, with different social priorities, he may have read these stories differently. Perhaps, as Tom Rasmussen has suggested, he understood the entire vase to be related to the mythical character Paris. [14] Maybe he saw Paris hunting near his rural home in the bottom register, fighting lions and making his Judgment in the middle register, and joining the Trojan War (which he incited with his Judgment) in the top register. Paris was a popular character in Etruria, and this seems as plausible a reading as that of Jeffrey Hurwit.

We need not choose a single interpretation of this vase’s decoration. The Chigi Vase passed through many hands before it was buried and did not have a single viewer. The Chigi Painter decorated it with one intention, while a Greek viewer may have read its meaning completely differently than an Etruscan viewer. The Chigi Vase was a mobile object that traveled through the Mediterranean before it was buried. Even 150 years after its discovery, we still debate its meaning while appreciating it as a marvelous work of art.

Notes:

[1] Jeffrey M. Hurwit, “Reading the Chigi Vase,” Hesperia, volume 71, number 1 (2002), pp. 3–6.

[2] Tom Rasmussen, “Interpretations of the Chigi Vase,” BABESCH, volume 91 (2016), p. 58.

[3] John Griffiths Pedley, Greek Art and Archaeology, 5th edition (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2012), pp. 122–25.

[4] Hurwit (2002), p. 8.

[5] In antiquity, different Greek regions used different alphabets when they wrote in the Greek language. Although the Chigi Vase was most likely made in Corinth, and the Chigi Painter was most likely Corinthian, the alphabet used in these labels is not Corinthian. Richard Neer, Art & Archaeology of the Greek World, 2nd edition (London: Thames and Hudson, 2019), p. 115 suggests that this might mean the Chigi Painter was not actually Corinthian, but moved to Corinth before he began making vases. It is also possible that someone other than the Chigi Painter wrote the labels in this scene.

[6] With its flame-like hair, the lion on the Chigi Vase closely resembles the lions that appear in Neo-Assyrian art, as in the palace reliefs of King Ashurbanipal. Hurwit (2002), p. 12 suggests that the Chigi Painter might have been inspired by similar lions he saw decorating objects imported from that region.

[7] Hurwit (2002), p. 10.

[8] Hurwit (2002), p. 19. Matteo D’Acunto, Il mondo del vaso Chigi. Pittura, guerra e società a Corinto alla meta del VII secolo a.c. (Boston: De Gruyter, 2013), pp. 172–74 comes to a similar conclusion.

[9] Robin Osborne, Greece in the Making, 1200–479 B.C.E. (New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 163–64 notes that these shield emblems probably imitate those that decorated the shields of real hoplites.

[10] Darrell A. Amyx, Corinthian Vase-Painting (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), p. 369.

[11] Neer (2019), p. 111.

[12] Neer (2019), p. 100.

[13] Hurwit (2002), pp. 16–19.

[14] Tom Rasmussen, “Paris on the Chigi Vase,” Cedrus, volume 1 (2013), pp. 55–64.

Additional resources

Black-Figure Vase Painting from the University of Colorado Boulder Department of Classics

Jeffrey M. Hurwit, “Reading the Chigi Vase,” Hesperia, volume 71, number 1 (2002), pp. 1–22.

Tom Rasmussen, “Paris on the Chigi Vase,” Cedrus, volume 1 (2013), pp. 55–64.