The breakdown of centralized control that characterized the First Intermediate Period brought a new sense of uncertainty to Egyptian culture, which had been so stable for centuries. The overlapping internal struggles between regional rulers in the north and south eventually ended with the Theban nomarchs defeating the rulers at Herakleopolis and bringing all of Egypt under a single king again.

The dynamic reunification of the Two Lands in ancient Egypt, in the period we call the Middle Kingdom, created new requirements for the king. No longer an aloof divine representative of the gods on earth, the king in the Middle Kingdom was expected to be more available to the people. This period also saw increased interactions with the outside world, the re-establishment of connections with Syria to the north and the establishment of forts reaching south deep into Nubia. Rich in literature (often of great knowledge and wit), this era also produced exquisite works of art. The cult of Osiris grew as did the number of Egyptians who could equip themselves for the afterlife, what we might recognize as a “middle class.”

Middle Kingdom (c. 2030–1640 B.C.E.)

During the Middle Kingdom (Dynasty 11–13), many of the principles of Egyptian culture that had emerged at its outset and been codified during the Old Kingdom were adjusted and redefined. These included significant shifts in religious practices, afterlife beliefs, and the ideology of kingship.

Mortuary complex of Mentuhotep (with the later mortuary complex of Hatshepsut beside it), Deir El Bahari, Egypt (photo: Steve F-E-Cameron, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nebhepetra Mentuhotep II re-unified Egypt and established the Middle Kingdom, which is often considered the classical period for Egypt’s politics, literature, and art. Although he ruled the unified country from the city of Memphis, as the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom had done, he built his innovative mortuary complex on the west side of the Nile at Thebes. He and his successors devoted considerable attention to the Theban region, adding to the already-established shrine of the local god Amun and building the initial core for the temple at Karnak (which would subsequently be added to by nearly every following ruler for millennia). There is evidence for vastly expanded royal patronage of divine temples all over Egypt during the Middle Kingdom. This campaign not only re-solidified the connections between the king and the gods, but was also a way to stress the king’s presence at key regional centers.

Twelfth Dynasty rulers focused their attention on restoring the glories of the Old Kingdom while accommodating the beliefs, innovations in style, and architectural forms that were introduced or developed at Thebes. These kings constructed a new royal residence in the Fayum region southwest of Memphis and were buried nearby in pyramids with elaborate temples. Unfortunately, due to the construction methods used and later stone mining, none survive in good condition. Unlike the solid limestone Old Kingdom pyramids, Middle Kingdom monuments of this type were built with a core of mud brick. After the outer casing stone was removed for reuse during the ancient and medieval eras, the brick cores were exposed, and have long since eroded.

Statue of Senwosret III (Senusret III), 1874–1855 B.C.E., 12th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, incised granite, found at the Temple of Mentuhotep, 122 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

During the middle of the Twelfth Dynasty, a fascinating shift in the way pharaoh was portrayed occurred. In texts of the period, the role of the “Good Shepherd” becomes emphasized and, around the same time, the weight of royal responsibilities becomes evident in representations of the king. This dramatic shift in style is most clearly seen in the facial features of images of Senwosret II, Senwosret III, and Amenemhat III. Looking at these heavy faces, with their creased brows and drooping mouths, it is clear that profound changes had occurred.

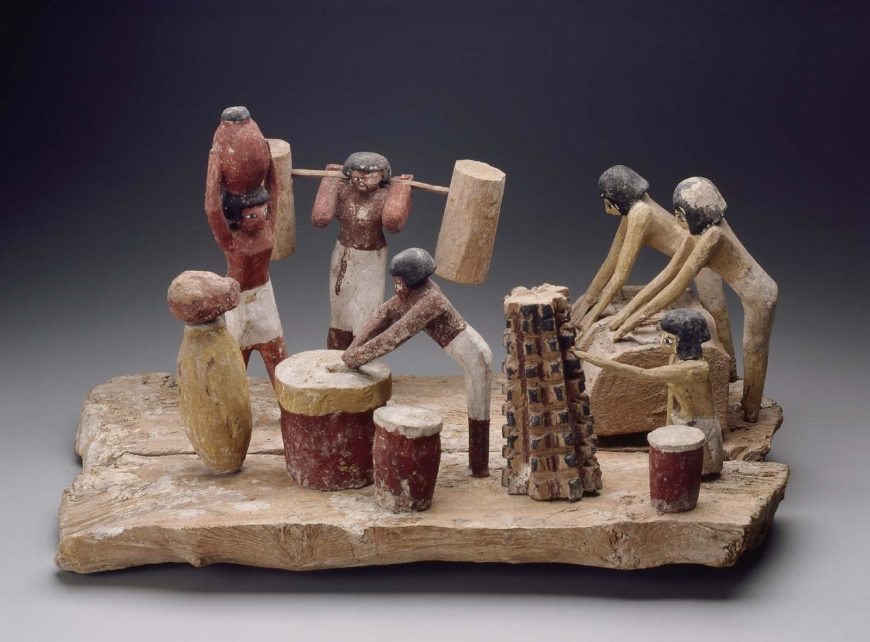

Model of a brewery, first Intermediate Period or Middle Kingdom, 2040–1991 B.C.E., painted wood, 28.5 x 32.5 x 53.5 cm (MFA Boston)

Elite necropolises carved into cliff sides along the Nile preserve non-royal aspects of the mortuary cult in this time. Much of the iconography in the tomb scenes is similar to late Old Kingdom, but new scenes also appear, including the representations of deities, especially the god Osiris. Models with figures in lively poses performing daily activities, like brewing, baking, and slaughtering cattle, were found in tombs of this era. Also during this period servant figures known as shabtis, which were designed to work for the deceased in the afterlife, began to appear. Private monuments dedicated to Osiris become prevalent and indicate a democratization of access to the divine, allowing more people the opportunity to interact with the gods.

Rectangular chest, cylinder seal, ingot, amulet, pendant, beetle, pearl, Treasure of Tod, dated to the reign of Noubkaoure Amenemhat II, materials: bronze, Egyptian alabaster, copper alloy, amethyst, silver, Egyptian blue, carnelian, rock crystal, copper, siliceous earthenware, jasper, lapis lazuli, mica, mother-of-pearl, obsidian, gold, bone, lead, flint, turquoise, glass, found under the temple of Montu at Tod (Louvre)

Rulers during the Middle Kingdom expanded control to the south into Nubia, building a series of mudbrick forts along the river as far south as Semna (below the Second Cataract) in order to better control the mines of gold and other valuable materials in the region, such as ebony, ostrich feathers, leopard skins, ivory, exotic animals, incense and a variety of hard stones. They also re-established trade routes to far-off Syrian cities for luxury goods such as cedar, wine, silver, and oil. There is evidence for robust trade interactions with other cultures as well: Minoan pottery sherds suggest trade with Crete and Asiatic artifacts, like large numbers of weights found in urban settings and the stunning assemblage of treasure discovered in four bronze chests under the temple of Montu at Tod, indicates connections beyond Syria-Palestine.

Pectoral and Necklace of Sithathoryunet with the Name of Senwosret II, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret II, c. 1887–1878 B.C.E., Egypt, Fayum Entrance Area, el-Lahun (Illahun, Kahun; Ptolemais Hormos), Tomb of Sithathoryunet (BSA Tomb 8), EES 1914, Gold, carnelian, feldspar, garnet, turquoise, lapis lazuli

This was a period of wealth and prosperity—a rich body of literature was produced, relief carvings of sublime beauty were created, bronze metalworking appears, and some of the most exceptional jewelry from the ancient world was crafted during this time. Several sets of highly-symbolic jewelry were discovered in the tombs of royal women. Imagery in the jewelry, statuary, and other depictions of royal women during this period show a strong connection between them and the goddess Hathor. Both the mother and wife of Horus in various myths, Hathor was also described as the mother, wife, or daughter of the sun god Ra—both male deities that the king was closely linked with. Royal women seem to have been viewed as mortal representatives of Hathor, serving a vital function in regeneration.

Head of a female sphinx, c. 1876–1842 B.C.E., Dynasty 12, Middle Kingdom, chlorite, 38.9 x 33.3 x 35.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Female sphinxes appeared during the Middle Kingdom, emphasizing a new connection between royal women in the fiercely protective role of the sun god’s daughter, the Eye of Ra. Although in general these developments in identity didn’t necessarily indicate significant changes in political status for royal women, it is interesting that the last king of the Twelfth Dynasty was the first known sole female ruler of Egypt, Nefrusobek.

By the Thirteenth Dynasty, centralized royal authority was again on the decline and control over Lower Egypt became more challenging. The ruling city of Lisht was abandoned and the kings reestablished the royal court and administrative seat in the southern city of Thebes. It would be nearly 150 years before a king would rule again over the united Two Lands.

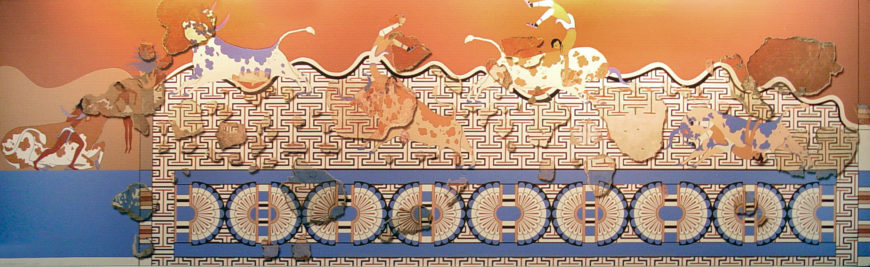

Reconstructed Minoan fresco showing bull-leaping from Avaris, Egypt. Now Archaeological Museum Iraklion, Crete, Greece (photo: Martin Dürrschnabel, CC-BY-SA-2.5)

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1640–1540 B.C.E.)

During the seventeenth century B.C.E., a group who originated in Western Asia and had blended into the local population of the delta region took control of the north of the country. Their kings were referred to as the hekau khasut, otherwise known as the Hyksos. These “rulers of foreign lands” established their own capital at Avaris and ruled the north, even calling themselves “Sons of Ra.” Archeological evidence shows that the community of Avaris had many decidedly non-Egyptian characteristics. Differences in house layouts, pottery types, weapons and tools, and burials being integrated into the settlement, as was common in western Asia, instead of separated (as was usual for the Egyptians), all point to a largely Syrio-Palestine population.

New words entered the Egyptian vocabulary during this period, as did Near Eastern deities, like Anat, and weapons including the scimitar and horse-drawn chariot. The international nature of the site is also evident in the startlingly Minoan-style murals of bull jumping, although these may date slightly later. Egyptian pharaohs still ruled from the south at Thebes, and there was a series of conflicts and battles for control. Textual evidence indicates that the king at Avaris was corresponding with the Nubian king of Kush at Kerma via the Western Oasis route in an effort to ally against the Egyptians at Thebes; their messengers were intercepted and communications cut off by the pharaoh Kamose who recorded his campaigns against them in stelae erected at Karnak temple. Eventually, Ahmose was successful in driving the Hyksos king out of the delta and re-unifying the land under a single ruler.

| Period | Dates |

| Predynastic | c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic | c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) | c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermedia Period | c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom | c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom | c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period | c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period | c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |