“Stay and mourn at the monument of dead Kroisos, who raging Ares slew as he fought in the front ranks.”

Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, looking at the “Anavysos Kouros.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:10] A sculpture from the Archaic period, the 6th century B.C.E. in ancient Greece.

Dr. Zucker: [0:16] It’s about life size, a little bit larger. The idea of monumental sculpture of an ideal male youth is a very powerful motif in Greek culture.

Dr. Harris: [0:27] Thousands of these figures were produced. We give them the generic name of kouros, or youth. They could be used as grave markers, as offerings in sanctuaries, and sometimes, though more rarely, they represent a god, usually the god Apollo.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] Some art historians think that perhaps these monumental sculptures were inspired by contact with ancient Egypt.

Dr. Harris: [0:48] You can see the resemblance to Egyptian sculpture very easily.

Dr. Zucker: [0:52] Look at the traces of the original paint in the hair, on the eyes. It gives us a sense of what this would have looked like initially.

Dr. Harris: [0:59] One of the things that happens when you talk about the kouros figures is that you compare them to one another because they’re of a type. There’s also the tendency to compare them to human bodies. How lifelike is it or how far from being lifelike is it?

Dr. Zucker: [1:12] In the earlier kouros, you have a greater sense of stiffness, of abstraction of the human body, where forms are represented almost as symbols rather than as an articulation of what we see in the human body.

Dr. Harris: [1:26] In those earlier figures, too, you have the sense of the body corresponding to a block of stone. You have four very distinct views. This particular kouros shows us the way that during the 6th century [B.C.E.], during the Archaic period, the figures become more natural, more lifelike, more rounded, less blocky.

Dr. Zucker: [1:45] Look at the swelling of the calves, of the hips, of the abdomen, and certainly of the arms and the cheeks. In earlier figures, what we saw was a kind of inscribing in the stone, almost as if you were drawing into the stone, whereas here you have modeling in the round.

Dr. Harris: [2:00] In some earlier figures, we see a hard line where the torso meets the legs. Here, that’s been softened, so there’s a more gradual transition.

Dr. Zucker: [2:09] The forms of the face are more integrated. In fact, the forms of the entire body, one piece to the next, one part of the body to the next, is more integrated. You see a more natural flow of the cheeks to the sides of the face, to the temples, to the forehead.

[2:23] There’s still continuity with these older standing nude figures. The left leg is out. Both knees are locked. The weight is evenly distributed on both legs. We still have the traditional braiding of the hair. We still have that traditional headband and those wonderful curls underneath it.

Dr. Harris: [2:39] Still that Archaic smile, which speaks of a figure that transcends this world, that has a sense of aristocratic nobility. In fact, this figure was set up by an aristocratic family as a grave marker to their son who died in war.

[2:55] There were often inscriptions on the bases of the kouros figures, and there was a base with an inscription found near the fine spot of this particular figure.

Dr. Zucker: [3:04] That was probably from about the same period and some art historians think that it belongs to this sculpture, some don’t. In any case, it’s instructive.

Dr. Harris: [3:12] The inscription reads, “Stay and mourn at the monument of dead Kroisos, who raging Ares slew as he fought in the front ranks.” Just to unpack that a little bit, Kroisos would be the name of the figure.

Dr. Zucker: [3:24] The man who died.

Dr. Harris: [3:26] Ares is the god of war, so this is obviously a youth who fell in battle, which is the most noble way to die, the way to die that’s associated with the ancient Greek heroes that we read about in the Iliad.

Dr. Zucker: [3:38] Look at the sense of potential, of this life that was cut short but at this moment of greatest strength, of greatest beauty. It’s important to recognize that this is not a portrait. This is not a specific individual.

[3:49] There’s a reference to an individual here, but the body that’s being represented is an ideal. It is a perfected body. As with so many of these standing male figures, the artist has had to leave a little bit of a bridge attaching the hands to the hips in order to strengthen the object.

Dr. Harris: [4:06] Or else the limbs could easily break off.

Dr. Zucker: [4:08] This figure was found in 1936 and was spirited out of Greece and was recovered by the Greek police in Paris and brought back a year later.

Dr. Harris: [4:19] The intention was to sell it on the market outside of Greece.

Dr. Zucker: [4:22] This has been a continuous problem, grave robbing of antiquities in Greece and in other countries, because the market is so strong. It’s created not only a black market for stolen objects but also a market for forgeries, which has complicated archaeological study.

Dr. Harris: [4:40] The good thing about this figure was that he was found, he was returned to Greece, and we can all see him here in the Archaeological Museum in Athens.

[4:47] [music]

Grave markers or votive offerings

In the late Archaic period, this over life-size statue stood above the grave of a man from a wealthy Greek family, grandly marking his tomb. With its idealized body, rigid posture, and distant gaze, the statue still commands attention today, long after it was completed around 530 B.C.E. By looking closely at the statue, we can learn quite a lot about the ancient Greeks who looked upon it centuries ago.

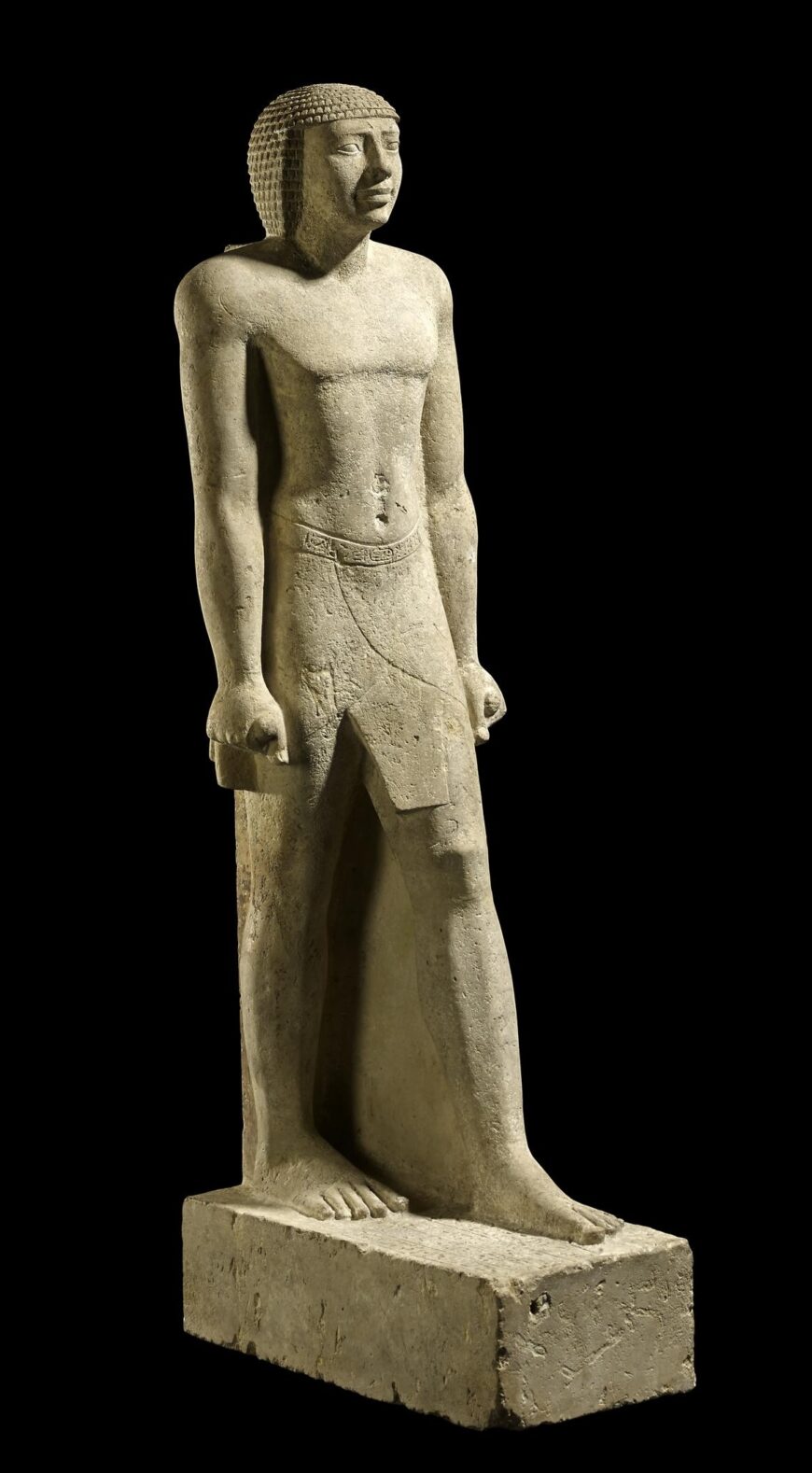

Tjayasetimu, c. 664–610 B.C.E., limestone, 4 feet 1.2 inches high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

This statue is an example of the kouros (plural: kouroi) type of Greek sculpture. The ancient Greek word kouros means “youth” or “young boy,” but we don’t know if the ancient Greeks called these statues kouroi—modern scholars were the first to use the term to describe them. [1] A kouros is a statue of a young, nude male. The young age of the kouros is evident in his beardless face, which indicates that he has not yet fully matured into adulthood.

Kouroi are usually entirely nude, though some wear headbands or necklaces. Although kouroi take one small step forward, placing their left foot in front of their right, they are rigid and stiff, holding their clenched fists close to their sides and tensing their muscles. Throughout the Archaic period, Greek sculptors made kouroi that functioned either as grave markers or as votive offerings given to the gods.

Influence of Egypt

The Greek sculptors who invented the kouros type may have been partially inspired by Egyptian stone sculptures. [2] Just before the beginning of the Archaic period, interactions between Greece and Egypt increased, creating more opportunities for Greeks to see Egyptian statues. Like Greek kouroi, Egyptian statues of elite men are often stiff and rigid, and they are made of stone, a durable and expensive material. However, there are two major differences between typical Egyptian sculptures of men and Greek kouroi. First, whereas kouroi are always nude, Egyptian sculptors usually showed men clothed (elites, like the priest named Tjayasetimu who is depicted in this image, wear kilts). Second, kouroi are fully separated from the block of stone from which they are carved. Although they are stiff, they stand without support. Many life-size Egyptian stone sculptures, including this one, rely on stone supports to stand up. These differences reveal that, while the Archaic Greeks may have taken Egyptian statues as inspiration, they created their own type when they invented the kouros.

Side view of the kouros’s head (detail), Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An ideal

For the Archaic Greeks, kouroi were the perfected images of masculinity. They embody a specifically Greek ideal. The Anavysos Kouros is one of the best preserved examples of this ideal. His face is symmetrical, with wide staring eyes and a slight smile. His smile is not meant to convey that he is happy. This expression, known as the Archaic smile, is instead intended to make the statue appear more lifelike. The hair of the kouros is also symmetrical and elaborately styled. Curls are arranged across the figure’s forehead, while long braids of hair fall down his back. This elaborate hairstyle conveys the wealth of the individual represented. A thin ribbon runs around the crown of the kouros’s head, seemingly holding a cap in place. [3] Traces of red pigment are still visible on the eyes and hair of the kouros’s head. [4] Like most ancient Greek statues, the Anavysos Kouros was originally brightly painted. Much of that paint has now faded, leaving the whitish marble visible.

Left: statue of a kouros (New York Kouros), c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

By comparing the Anavysos Kouros to an earlier kouros, we can see how the style of kouroi—and the ideal they embody—evolved throughout the Archaic period. Like the Anavysos Kouros, the New York Kouros is stiff and rigid. Both kouroi stand with their hands clenched at their sides and take one step forward with their left legs. Both have patterned hair and Archaic smiles. Both also originally functioned as grave markers and were probably set up close to each other in the same cemetery. [5] However, the Anavysos kouros is more naturalistic, or lifelike, than the New York Kouros in several ways. The Anavysos Kouros has much more rounded, fully developed muscles than the New York Kouros does. In comparison, the muscles of the New York Kouros look almost like patterns carved into the stone rather than volumetric muscles. The face of the Anavysos Kouros is also more naturalistic than that of the New York Kouros, with more realistically proportioned facial features and more attention to the transitions between parts of the body.

To create a more naturalistic image, the sculptor of the Anavysos Kouros has carved further into the block of marble than the sculptor of the New York Kouros did. Although the Anavysos Kouros’s hands are still attached to his thighs by small pieces of marble, ensuring that they would not break off, these supports are much smaller than the larger attachments that fuse the New York Kouros’s hands to his sides. The Anavysos Kouros’s rounded muscles make him appear fleshier and more lifelike. He is still idealized—no real person could actually be this symmetrical—but he is more naturalistic than the New York Kouros, which was made 50 years before he was.

Torso of the kouros, with the modern break still visible above the navel (detail), Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Not discovered by archaeologists

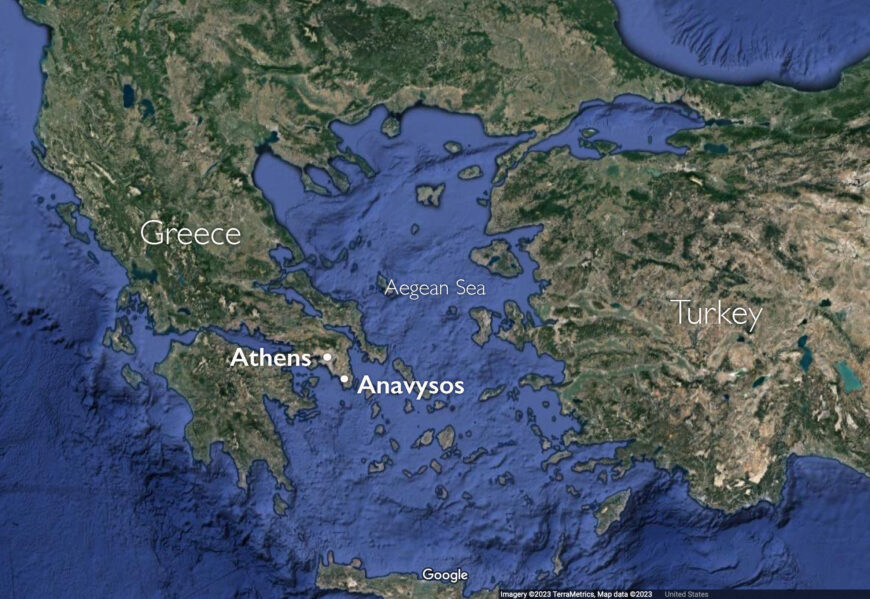

This statue is called the Anavysos Kouros because it was found near the town of Anavysos in Greece. Unfortunately, this statue was not discovered by archaeologists. Looters first uncovered the kouros in 1936, and soon smuggled it out of Greece so that it could be sold in Paris. In order to get the large statue out of the country, the smugglers sawed it into ten pieces. [6] One of their cuts is still visible just above the kouros’s navel. When the statue was returned to Greece in 1937, conservators were able to piece almost all of it back together, mending much of the damage that was done.

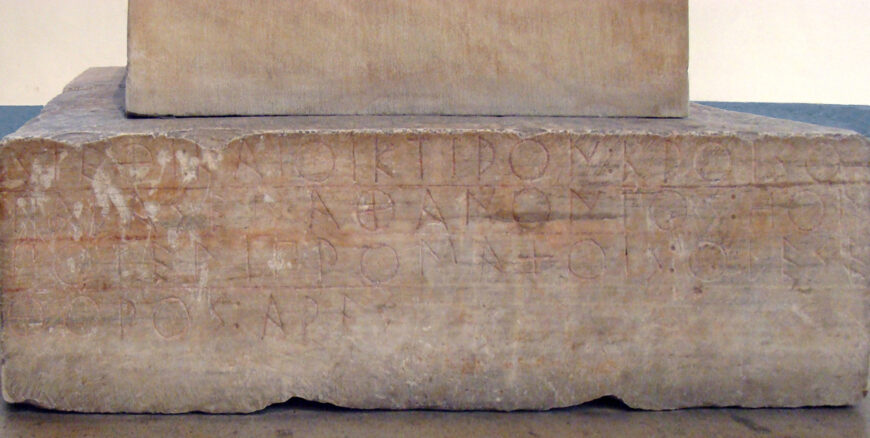

Front of statue base probably originally associated with the Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 9.45 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: F. Tronchin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Almost 20 years after the Anavysos Kouros was returned to Greece, a statue base found near Anavysos was given to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Many scholars believe that the Anavysos Kouros originally stood atop this base. The base is inscribed with ancient Greek text that commemorates the person whose grave it marked. In translation, the text reads: “Stay and mourn at the monument for dead Kroisos whom violent Ares destroyed, fighting in the front ranks.” [7]

This moving inscription tells us much about the person who was buried beneath it. His name was Kroisos, and he died while fighting in a war. [8] He is celebrated as an accomplished warrior, “fighting in the front ranks” against the enemy, destroyed by “violent Ares,” the god of war himself. The text encourages viewers to “stay and mourn” the deceased. Together with the kouros that stood above it, it demands the attention of passersby and asks them to remember the man it memorializes.

The Anavysos Kouros is an idealized representation of a man in his prime. Kroisos could not have actually looked like this statue. No real, living person is so symmetrical or stiff. Moreover, Kroisos was a soldier, and so he must have been a bearded adult when he died. [9] But this statue is not intended to depict Kroisos as he actually appeared. It instead presents an image of a perfect man, as imagined by the Archaic Greeks. His nudity allows him to show off his perfected musculature, which conveys his strength. The wealthy family who had this statue made to mark the grave of their dead loved one chose it because it would forever project an image of perfection, making the ideal memory of their relative permanent in stone.