Left: Constantin Brȃncuși, Sleeping Muse I, 1910, marble, 17.2 x 27.6 x 21.2 cm (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.); right: Head of an Early Cycladic figurine, 2600–2400 B.C.E., marble, 14 x 27 x 10 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Consequences of collecting

In the early 1900s, as European artists explored new ways of representing the human form, many took inspiration from sculptures that were thousands of years old. Famous artists including Constantin Brȃncuși and Pablo Picasso were captivated by the sparse simplicity of marble figures made in the Cyclades between c. 3200 B.C.E. and 2300 B.C.E. [1] These ancient stone sculptures represent people simply. Their arms and legs are marked by incisions, often not even separated from the body. Their faces only have sculpted noses, while the rest of the facial features (once added in paint) are now usually invisible to the modern viewer. Although they are simplified, these statues are still easily recognizable as people. Their minimalism inspired modern artists and made the statues seem almost modern themselves, contributing to their popularity amongst collectors.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Cycladic figures became immensely popular on the art market. Collectors paid millions of dollars to purchase Cycladic statues at auctions. The economic potential of these figures led looters to seek them out. Looters illegally removed hundreds of marble figures from the Cyclades, selling them to dealers who then realized significant profits. The popularity of Cycladic figures on the market has also resulted in a proliferation of forgeries. It is difficult to assess the true extent of this looting, but current statistics about the provenance of Cycladic figures give us an idea of how much damage it caused: although well over a thousand Cycladic figures are known today, only about 200 of them come from excavations conducted by trained archaeologists. [2]

The widespread looting of Cycladic statues had disastrous consequences for our understanding of them. When an artifact is removed from its original context by a non-expert, valuable information is lost. So many Cycladic figures entered modern collections without archaeological data that we are still unsure of what the statues’ identities and functions originally were. [3] In the following paragraphs, we will consider what we do know about Cycladic figures, including where they were made, how their appearances evolved over time, and what their forms can tell us about their possible original functions.

Marble quarry in Naxos (photo: Heiko Gorski, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Natural resources on the Cyclades

The Cyclades’ natural resources enabled their inhabitants to make marble sculptures. People living in the Cyclades during the Early Cycladic period traveled between the islands regularly, trading with one another and acquiring materials from their neighbors. Many Cycladic islands have extensive supplies of high quality marble. While some small Early Cycladic figures might have been made from found pebbles or stones, other larger figures were probably crafted from thin blocks of marbles taken from quarries on Naxos or Paros. [4] Once an Early Cycladic craftsman acquired a piece of marble, he used tools made from hard, locally available materials (like obsidian) to carve it and incise details into its surface. [5] He then used emery, another mineral that is naturally prevalent in the Cyclades, to smooth the statue down to its final shape. [6] Finally, the statue was painted.

We do not have enough archaeological evidence to determine whether Early Cycladic craftspeople traveled between islands to work for different customers, or whether their products were traded by merchants. [7] Our understanding of Early Cycladic societies and sculptors is further limited because they did not use written language, and so left no written records for us to read. However, we do know that their work was facilitated by the rich natural world in which they lived.

“Violin” type Early Cycladic figurine, 3200–2700 B.C.E., marble, 21.9 x 7.6 x 1.9 cm (The Menil Collection, Houston)

Stylistic simplicity in Early Cycladic figurines

Most Early Cycladic statues represent women. [8] The earliest Cycladic figurines tend to represent women in a more abstracted, schematic manner than their later counterparts. These early statues are often referred to as “violin” figurines because their overall shape recalls that of a violin. [9] One well-preserved example in the Menil Collection reveals how even these simplified violin figures can be recognized as female. Although the figure has no defined head or limbs, it does have an incised pubic triangle, marking it as a woman. These simplified violin figures were especially popular during the first phase of Early Cycladic culture, from c. 3200–2700 B.C.E. [10]

Front and side views of an Early Cycladic folded-arm figurine, 2700–2500 B.C.E., marble, 49.5 x 9 x 6 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Around 2700 B.C.E., Cycladic sculptors developed a new kind of female figurine that soon came to dominate production. Today scholars refer to these statues as folded-arm figurines, or FAFs, because they are shown with their arms folded across their middles. [11] Although FAFs are simplified, they are more naturalistic than the violin figures that preceded them. We can see all of the typical features of FAFs on one statue in the Getty Museum. Overall, the figure is elongated. Its wedge-shaped head is tilted back and only its nose is sculpted. Other facial features that were originally added in paint have now mostly faded away. The woman has small articulated breasts, which indicate that she is female. Her arms fold over her abdomen, the left resting atop the right. Her legs are bent slightly at the knees and are not entirely separated from one another. When we consider the sculpture from the side, we see that its feet are not flat: the toes point slightly downwards. Like most other FAFs, this sculpture would not have been able to stand up on its own. Although modern museums often display FAFs upright, they must have been laid on their backs or propped up against walls in antiquity. [12]

Left: The Bent Sculptor, Early Cycladic figurine, 2700–2500 B.C.E., marble, 17.1 x 5.7 x 2.9 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris); center: The Bent Sculptor, Early Cycladic Figurine, 2700–2500 B.C.E., marble, 14.9 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London); right: The Bent Sculptor, Early Cycladic Figurine, 2700–2500 B.C.E., marble, 18 x 5.5 x 8.5 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge)

Cycladic sculptors made hundreds of folded-arm figurines between 2700 and 2300 B.C.E. [13] They are easily recognizable because of their basic shared characteristics, but they vary somewhat in their details and proportions. Our lack of understanding of these objects’ functions makes it difficult to explain these minor variations. However, some of these distinctive details may be the result of individual artisans’ preferences. In fact, some groups of folded-arm figurines are so similar to one another that art historians have proposed they are made by the same individual. One such craftsman has been named the Bent Sculptor after an archaeologist who worked in the Cyclades many years ago. [14] The Bent Sculptor’s folded-arm figurines are relatively stocky, with wide shoulders, narrow waists, and pointed chins. [15] While it is remarkable that we may be able to identify one person who made several Cycladic figures, the usefulness of this information is limited because we do not know where exactly the figures are from, and thus cannot determine where they were made or how they were used.

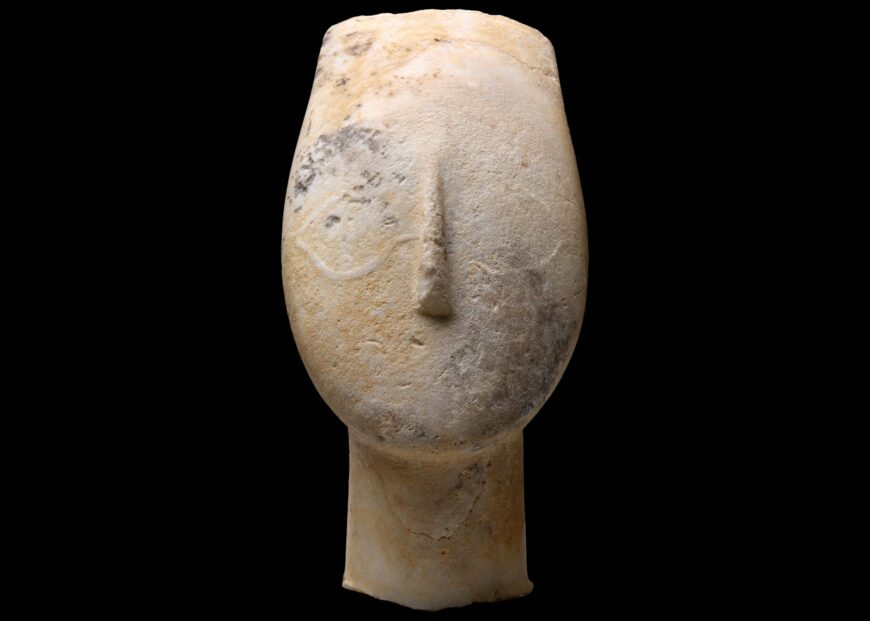

Head of an Early Cycladic figurine, 2700–2500 B.C.E., marble, 25.3 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Painted people

Although a lack of archaeological context makes it impossible to determine the original functions of most Cycladic figures, some of the statues provide tantalizing clues on their own surfaces. The seeming simplicity of the folded-arm figurines is partially deceptive: nearly all of the figures were originally painted, particularly on their faces. In the Early Cycladic period, these figures had eyes rendered with bright red and blue paints made from local minerals. These painted decorations are often only barely visible today. Sometimes, the areas that were once painted appear slightly raised above the stone around them because the painted portion was protected by the (now missing) paint. [16] Such raised traces, which are called “ghosts” by archaeologists, are visible on the head of one figurine that is now in New York. The curving lines of the figure’s eyes are visible on either side of its slender nose, revealing that it once fixed viewers with an attentive stare.

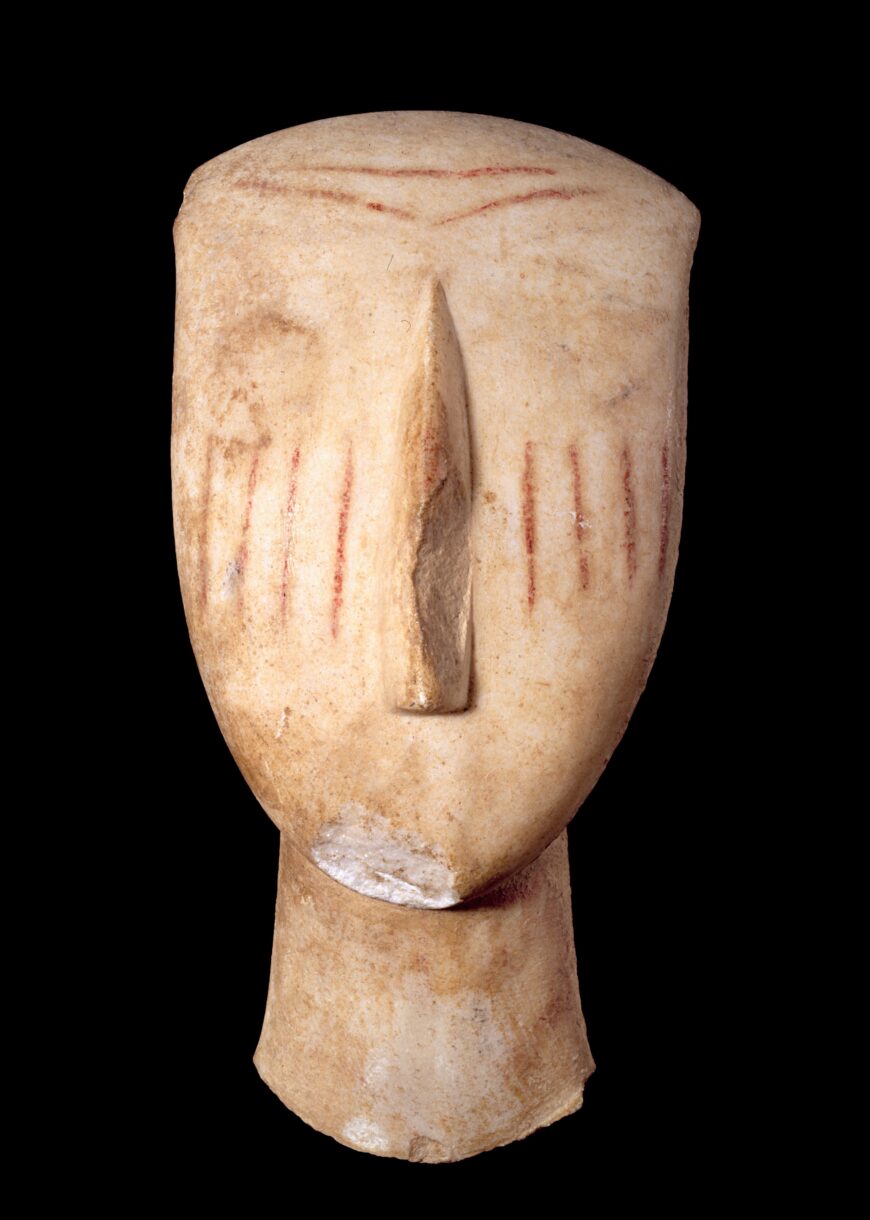

Head of an Early Cycladic figurine, 2600–2500 B.C.E., marble, 22.8 x 8.9 x 6.4 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Head of an Early Cycladic figurine, 2700–2300 B.C.E., marble, 24.6 cm (National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen)

Many Cycladic figures have patterns painted on their faces. For example, a head that once belonged to an exceptionally large statue has a series of vertical red lines on its forehead, rows of red dots on its cheeks and chin, and a red stripe down its nose. These painted details do not correspond to facial features. They might instead relate to actual face painting rituals that may have been performed by Early Cycladic peoples during important life events. [17] In her groundbreaking interpretation of the paint on Cycladic figures, Gail Hoffman suggested that the statues were painted multiple times throughout their existence to reflect the changes their owners underwent. [18] A person might acquire a figure early in her life, painting its face with the markings she herself wore to her wedding when she got married, and later re-painting it with the patterns she wore during the dangerous time of childbirth.

Finally, when a person died, her figure might be repainted once more to depict a state of mourning. Several Cycladic figures with long vertical lines on their faces might reflect funerary rituals during which women lacerated their faces in anguish. [19] Other interpretations of the painting on Cycladic figures’ faces suggest that the markings reflect clan memberships. [20] Without written texts or more archaeological evidence, it is impossible to tell for sure what the markings mean.

Reconstruction of a Cycladic figurine with paint by Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann (Polychromy Research Project, Liebieghaus, Frankfurt)

Context clues

The few Cycladic figures that were excavated by trained archaeologists were mostly found in graves. Given this clue, and the fact that a few have been found painted with facial markings that might relate to mourning, it seems possible that some of the statues served a funerary function. However, only some excavated Cycladic tombs have figurines, and some very rich burials lack marble statues. Not all deceased elites needed marble figures in their graves. [21]

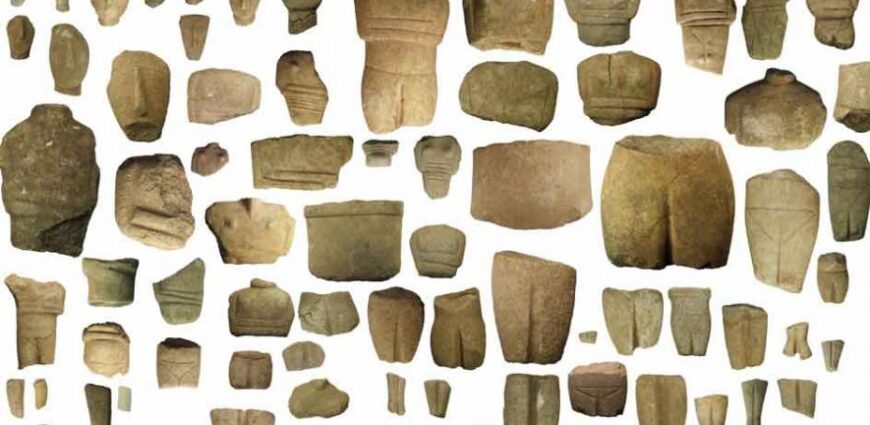

Fragments of Early Cycladic figurines found on the island of Keros (Island of Broken Figurines, Keros Project, Cambridge University)

In recent years, excavations on the island of Keros have revealed evidence that the marble figurines were used in rituals. Archaeologists have discovered hundreds of fragments of Early Cycladic statues buried in two closely related deposits on Keros. While one of these deposits has been extensively looted and essentially destroyed, the other is partially preserved, allowing archaeologists to study it more carefully. [22] The fragments found here come from hundreds of different Early Cycladic figurines. There is no evidence that the statues were broken near the deposit where they were buried. Moreover, the many fragments of figurines do not join with one another: they all come from different figures. Keros is a small island that did not have a large population in the Early Cycladic period. As a result, archaeologists believe that these deposits on Keros were a destination for people throughout the Cyclades. They suggest that Early Cycladic peoples may have broken their figurines at home, on whichever island they inhabited, and then carried a single piece of their figurine to the large deposits on Keros, where they buried them together with the many other fragments that accumulated over the decades. [23]

For now, any conclusions we reach about the original functions of these statues remain unconfirmed. New excavations shed more light on the figures’ significance, but extensive looting has resulted in an irreversible loss of knowledge. We can still appreciate the accomplishments of the craftsmen who created Cycladic figures. Using sparse, simplified forms, they crafted easily recognizable human figures with locally available materials. Although the Early Cycladic figurines’ exact functions are unknown, the great number of surviving examples and their relatively wide distribution throughout the Cyclades suggests that they were important to the islands’ inhabitants. As Alexander Aston has recently proposed, we might best understand them as material links in an imaginary chain that connected Early Cycladic peoples across the sea that separated them. [24] Even while living on different islands miles away from one another, these individuals all shared the ability to understand the marble figurines that circulated amongst them. As Early Cycladic peoples decorated their statues, buried them in graves, or left them in communal deposits on Keros, they remained connected through their shared use of the small marble figurines. Until the Early Cycladic culture came to an abrupt end around 2000 B.C.E. under mysterious circumstances, these statues were an essential part of its identity.