Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This small ancient Greek sculpture shows two figures facing each other at close proximity. Each stands just a few inches tall, stiffly holding onto the other’s arms. Although the figures are reduced to basic forms, they are still recognizable. The taller character is a man. He has a large head, thin chest, and muscular lower half. He wears nothing except for a conical helmet and a belt. Opposite the man stands a slightly shorter, more unusual being. The front half of this monster appears to be human, but the back half of a horse emerges from his human waist. Half-horse, half-man creatures like this one are known as centaurs.

Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Considering the same sculpture from a different angle reveals more about the story it tells. From here, we can clearly see that the centaur and the man are grappling with one another. Their movements are stiff, but the centaur’s left hand tightly grasps the right arm of his human opponent. At first glance the battle seems undecided. However, one small detail indicates that the centaur is doomed to lose: a small, rectangular object is embedded into his left flank. This is the handle of a sword or spear that the man has buried into the centaur’s side, seriously wounding him and ensuring his defeat. [1] This simple bronze statue actually represents a detailed narrative of combat between man and monster, and hints at the man’s impending victory.

Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Back of man (detail), Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Sparse style

The man and centaur statue group is an excellent example of an artwork made in the Greek Geometric style. The Geometric style was most popular from 900–700 B.C.E., a period of Greek history which is now known as the Geometric period because of the style. The Geometric style is characterized by the use of basic shapes to create representations that are easy to understand. The rigid sparseness of the Geometric style is evident in both figures.

When we look more closely at the man, we find that his head is a simple, round shape, essentially a circle, with a small triangle representing a pointed beard emerging from his chin. [2] His torso is an upside down triangle, which emphasizes his broad, muscular shoulders and slim waist (which is further accentuated by his belt). His arms and legs are cylinders that bulge in places to give the impression of having muscles. Although this style might at first appear simplistic, its simplicity is intentional. Figures represented in the Geometric style are recognizable because of their sparseness. They are legible, but do not overwhelm viewers with extraneous details that might distract from their overall clarity.

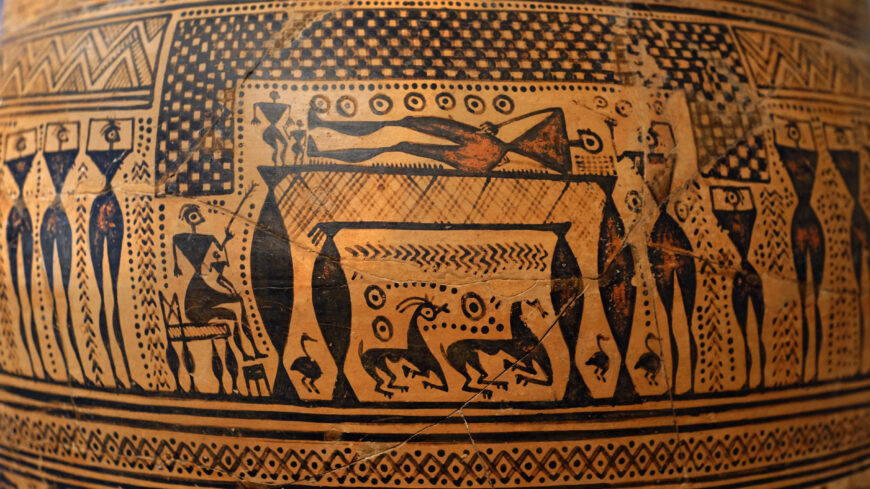

Krater, attributed to the Hirschfeld workshop, c. 750–735 B.C.E., terracotta, 108.3 x 72.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The same sparse style is also used on vases made during the Geometric period. In this detail of a large Geometric vessel, we see a funerary scene. The deceased lies on a bed as others stand near him and mourn. In this image, we again see how Geometric artisans pared human figures down to basic shapes, with triangular torsos, broad shoulders, thin waists, and simple, rectangular legs.

Geometric votives

Greek civilization evolved dramatically in the Geometric period. The written Greek alphabet emerged. Regions began to organize into formal city-states. As these major developments occurred, people living throughout the Greek world also began building sanctuaries where they could worship their gods together. These sanctuaries became larger and more elaborate as the Geometric period continued and more and more people visited them. Many devotees brought gifts to these sanctuaries, which they dedicated to the gods in hopes of receiving blessings in return. These gifts, which are known as votive offerings, often remained on display in the sanctuary long after they were dedicated. This ensured that the gifts would be seen by the gods and other worshippers. Small bronze statues were especially popular votive offerings during the Geometric period. Worshippers who dedicated these relatively expensive objects simultaneously demonstrated their wealth and religious devotion. The practice of offering votives to the gods continued throughout Greek history.

Left: Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: statuette of a horse, c. 740 B.C.E., bronze, 6.4 cm high (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The man and centaur group probably originally functioned as a votive offering at a sanctuary. Its specific findspot is unknown, but it is said to have been found at Olympia, where there was a major sanctuary sacred to Zeus. [3] Thousands of Geometric style bronze figurines were dedicated as votive offerings at Olympia during the 8th century B.C.E., towards the end of the Geometric period. [4] Most of these figurines represent single animals—group sculptures like the man and centaur are relatively rare. However, the sparse form of these simpler figurines still recalls the simplicity of the man and centaur. Like the man and centaur, this horse found at Olympia stands on a rectangular base that is decorated with abstract patterns. The horse is made up of a series of basic shapes: its legs, tail, and snout are cylinders, its body is a rectangle, and its neck and ears are triangles.

It is possible that this horse (and some of the hundreds of others that resemble it) was made in the same workshop as the man and centaur group. [5] When these artifacts were made, many craftsmen worked in shops near major religious sanctuaries like the one at Olympia so that they could sell their wares to the thousands of people who traveled there to worship the gods. One industrious metalsmith might have innovated on the more traditional single figurines he usually made and instead created a narrative group, which he then sold at a higher price to an individual who subsequently dedicated it as a votive. [6]

Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Production process

Crafting this group statue required a lengthy production process that further heightened the object’s value. The statue is mostly made of solid bronze. The metalworker who made it used the complicated solid lost-wax casting method to create the sculpture. [7] First, he made a detailed model of the statue in wax. When he was satisfied with the wax model, he carefully covered it in clay. He then put the clay-covered wax model into a kiln to harden the clay and melt the wax within. Subsequently, the metalworker poured the melted wax out of the hardened clay mold. He then poured molten bronze into the clay mold, so that the metal filled the empty spaces left behind by the wax. When the metal cooled and hardened, the metalworker removed the clay mold that surrounded it, leaving the solid bronze figurine. He might have refined some of the statue’s details after he removed the clay mold.

Faces of the man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

To make this particular statue group even more elaborate, the craftsman then added the figures’ eyes in different materials. Scientific analyses have determined that the man’s eyes (which are now lost, leaving their sockets hollow) were made of silver, while the centaur’s eyes were made of iron. [8] The man’s eyes would have shone in their deep sockets, while the centaur’s eyes would have appeared reddish in color, making the two characters contrast even more strongly. [9]

Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Moral of the story

The materials, style, and expense of the man and centaur group made it a worthy votive offering. But why would a Greek worshipper want to dedicate a statue group that shows a man and centaur fighting? Scholars have long debated who the victorious man in this statue group is. His dominance over the centaur suggests he is a hero, but because he does not have any easily identifiable characteristics, we cannot tell which exact hero he is. [10] During the Geometric period, Greek myths were just beginning to become consistent, and it is possible that this statue brought to mind different stories for different people at Olympia. [11] In any case, the exact identity of the hero represented here does not affect our understanding of the narrative’s morals. [12] The group shows a man triumphing over a creature that is half-animal. The man—who would have been much more relatable to the typical Greek viewer—will defeat the centaur—who is partially wild. [13] The battle between man and centaur is a metaphor for the battle between the civilized and the uncivilized. As Greek civilization evolved and Greek territories expanded, Greek citizens increasingly emulated strong mythical heroes who beat monstrous opponents. They continued to depict battles between men and centaurs for centuries. [14] This small statue shows one of their earliest experiments with a story that came to symbolize the strength of their community. With its sparse forms and expensive materials, this Geometric artifact reveals the values of the person who dedicated it millennia ago.