Trajan expanded the Roman Empire to its greatest extent, celebrating his victories with this monumental column.

Column of Trajan, Rome, completed 113 C.E., Luna marble, dedicated to Emperor Trajan (Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus b. 53 , d. 117 C.E.) in honor of his victory over Dacia (now Romania) 101–102 and 105–06 C.E. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Column of Trajan, Luna marble, completed 113 C.E., Rome, dedicated to Emperor Trajan (Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus b. 53 , d. 117 C.E.) in honor of his victory over Dacia (now Romania) 101–02 and 105–06 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Triumph

Returning from Dacia triumphant—100 days of celebrations

Iconography and themes

The execution of the frieze is meticulous and the level of detail achieved is astonishing. While the column does not carry applied paint now, many scholars believe the frieze was initially painted. The sculptors took great care to provide settings for the scenes, including natural backgrounds, and mixed perspectival views to offer the maximum level of detail. Sometimes multiple perspectives are evident within a single scene. The overall, unifying theme is that of the Roman military campaigns in Dacia, but the details reveal additional, more subtle narrative threads.

Specifications of the column and construction

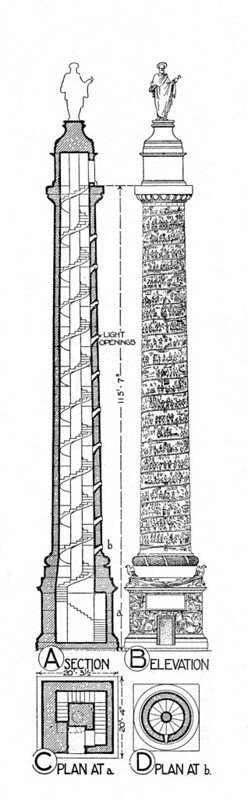

The column itself is made from fine-grained Luna marble and stands to a height of 38.4 meters (c. 98 feet) atop a tall pedestal. The shaft of the column is composed of 19 drums of marble measuring c. 3.7 meters (11 feet) in diameter, weighing a total of c. 1,110 tons. The topmost drum weighs some 53 tons. A spiral staircase of 185 steps leads to the viewing platform atop the column. The helical sculptural frieze measures 190 meters in length (c. 625 feet) and wraps around the column 23 times. A total of 2,662 figures appear in the 155 scenes of the frieze, with Trajan himself featured in 58 scenes.

Significance and influence

Additional resources

Trajan’s Column in Rome, from Prof. R. Ulrich, Dartmouth College

National Geographic Society—Column of Trajan

Wikimedia Commons—Cichorius Plates

M. Beckmann, “The “Columnae Coc(h)lides” of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius,” Phoenix, volume 56, numbers 3/4 (2002), pp. 348–57.

F. Coarelli et al., The Column of Trajan (Rome: German Archaeological Institute, 2000).

A. Curry, “A War Diary Soars Over Rome,” National Geographic (2015).

G. A. T. Davies, “Topography and the Trajan Column,” Journal of Roman Studies, volume 10 (1920), pp. 1–28.

G. A. T. Davies, “Trajan’s First Dacian War,” Journal of Roman Studies, volume 7 (1917), pp. 74–97.

P. Davies, “The Politics of Perpetuation: Trajan’s Column and the Art of Commemoration,” American Journal of Archaeology, volume 101, number 1 (1997), pp. 41–65.

M. Henig, editor, Architecture and Architectural Sculpture in the Roman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology: Distributed by Oxbow Books, 1990).

T. Hölscher, The Language of Images in Roman Art, translated by A. Snodgrass and Annemarie Künzl-Snodgrass (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

N. Kampen, “Looking at Gender: The Column of Trajan and Roman Historical Relief,” in Domna Stanton and Abigail Stewart, eds. Feminisms in the Academy (Ann Arbor 1995), pp. 46–73.

G. M. Koeppel, “Official State Reliefs of the City of Rome in the Imperial Age. A Bibliography,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II,12,1 (1982), pp. 477–506.

G. M. Koeppel, “Die historischen Reliefs der römischen Kaiserzeit VIII, Der Fries der Trajanssäule in Rom, Teil 1: Der Erste Dakische Krieg, Szenen I-LXXVIII,” Bonner Jahrbücher, volume 191 (1991), pp. 135–97.

G. M. Koeppel, “Die historischen Reliefs der römischen Kaiserzeit IX, Der Fries der Trajanssäule in Rom, Teil 2: Der Zweite Dakische Krieg, Szenen LXXXIX-CLV,” Bonner Jahrbücher, volume 192 (1992), pp. 61–121.

G. M. Koeppel, “The Column of Trajan: Narrative Technique and the Image of the Emperor,” in Sage and emperor: Plutarch, Greek intellectuals, and Roman power in the time of Trajan (98–117 A.D.), edited by Philip A. Stadter and Luc Van der Stockt (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2002), pp. 245–58.

Lynne Lancaster, “Building Trajan’s Column,” American Journal of Archaeology, volume 103, number3 (1999), pp. 419–39.

E. La Rocca, “Templum Traiani et columna cochlis,” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Römische Abteilung, volume 111 (2004), pp. 193–238.

F. Lepper and S. Frere, Trajan’s Column: A New Edition of the Cichorius Plates (Gloucester U.K.: Alan Sutton, 1988).

S. Maffei, “Forum Traiani: Columna,” in Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, volume 2, edited by E.M. Steinby (Rome: Quasar, 1995), pp. 356–59.

C. G. Malacrino, “Immagini e narrazioni. La Colonna Traiana e le sue scene di cantiere,” Storia e narrazione. Retorica, memoria, immagini edited by G. Guidarelli and C.G. Malacrino (Milan: B. Mondadori, 2005), pp. 101–34.

A. Mau, “Die Inschrift der Trajanssäule,” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 22 (1907), pp. 187–97. [accessible via Google Books].

J. E. Packer, “Trajan’s Forum again: the Column and the Temple of Trajan in the master plan attributed at Apollodorus (?),” Journal of Roman Archaeology, volume 7 (1994), pp. 163–82.

I. A. Richmond and M. Hassall, Trajan’s Army on Trajan’s Column ( London: British School at Rome, 1982).

L. Rossi and J.M.C. Toynbee, Trajan’s Column and the Dacian Wars (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971).

E. Togo Salmon, “Trajan’s Conquest of Dacia,” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, volume 67 (1936), pp. 83–105.

S. Settis et al., La Colonna Traiana (Turin: G. Einaudi, 1988).

H. Stuart-Jones, “The Historical Interpretation of the Reliefs of Trajan’s Column,” Papers of the British School at Rome, volume 5 (1910), pp. 433–59.

E. Wolfram Thill, “Civilization under Construction: Depictions of Architecture on the Column of Trajan,” American Journal of Archaeology, volume 114, number 1 (2010), pp. 27–43.

M. Wilson Jones, “One Hundred Feet and a Spiral Stair: Designing Trajan’s Column,” Journal of Roman Archaeology, volume 6 (1993), pp. 23–38.

M. Wilson Jones, “Trajan’s Column,” chapter 8 in Principles of Roman Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), pp. 161–76.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Column of Trajan,”]