Archaic ideals

From 600 to 480 B.C.E., ancient Greek cemeteries and sanctuaries were filled with marble statues of beautiful young men and women. The images of nude young men are today called kouroi (singular: kouros), the ancient Greek word for boy, though we do not know if they were called kouroi in antiquity. Their female counterparts, korai (singular: kore), wear richly painted robes and accessories made of expensive metals. Kouroi and korai are highly idealized images. Rather than showing people as they actually looked, they are representations of youthful perfection as envisioned by the Greek aristocrats who commissioned them in the Archaic period. These elite individuals conflated bodily beauty with moral excellence, so from their viewpoint, the idealized statues of young men and women that they commissioned displayed both inner and outer greatness. Kouroi and korai broadcasted the wealth and ideals of their patrons, revealing much about Archaic society.

Origins of kouroi and korai

Greek sculptors began to experiment with making statues out of marble in the second half of the seventh century B.C.E. The earliest examples of marble kouroi come from Naxos and Paros, Cycladic islands with natural supplies of marble. Greek artists and patrons may have been inspired to create kouroi after seeing life-size stone sculptures of men and women in Egypt, which opened its borders to foreigners around 650 B.C.E. Greek kouroi borrow their stiff, upright postures from Egyptian statues of humans (such as King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen).

Partly carved marble Kouros in situ, Naxos quarry (photo: John Winder, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A few unfinished kouroi that were abandoned in quarries on Naxos show us that sculptors did much of their preliminary work before the marble block was moved from its excavation site. They probably began to sculpt the block into a kouros before it was sent to its final destination to reduce its weight, allowing for easier transport. Sculptors likely traveled with the partially sculpted blocks to finish them near where they were erected.

Statue of a woman (Lady of Auxerre), c. 640–630 B.C.E., Daedalic (Early Archaic), Greek, possible Crete, limestone, 75 cm high (Louvre; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Shortly after the kouros form was invented in Naxos, clients from other Greek cities began to commission kouroi. In the first half of the sixth century B.C.E., Naxian and Parian sculptors made kouroi for patrons in Attica and Boeotia in mainland Greece, and exported statues to sanctuaries throughout the Greek world.

Left: detail from King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen (Egyptian Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4), 2490–2472 B.C.E., greywacke, 42.2 x 57.1 x 55.2 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, photo left: Hrag Vartanian, CC BY ND 2.0) Right: Statue of a woman (Lady of Auxerre), c. 640–630 B.C.E., Daedalic (Early Archaic), Greek, possible Crete, limestone, 75 cm high (Louvre; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Korai became popular soon after kouroi. Like kouroi, many of the earliest korai were made in the Cyclades, but they do not seem to have been based on Egyptian models. Whereas early korai are extremely modest and show almost no indication of their bodies beneath their robes, Egyptian statues of women tend to show more of their form. Greek sculptors may instead have been inspired by images of women they saw on Near Eastern objects like metal vessels and elaborately decorated furniture, which were imported into Greece in large quantities during the Archaic period. They may also have adapted their previous works in the Daedalic style. Daedalic sculptures of women (like the Lady of Auxerre) are richly dressed and rigid like the korai that followed them, but korai are rounder and more columnar than Daedalic statues, embodying a new ideal of feminine beauty.

The changing ideal

Standard kouroi and korai are easily recognizable because of their shared characteristics. They are made of marble and stand in stiff, upright postures. They have Archaic smiles that imbue them with a sense of vitality. Their hair is elaborately coiffed, and korai sometimes wear metal headpieces. Kouroi are nude, displaying their slim, athletic bodies, but korai always appear clothed in luxurious dresses and cloaks. Whereas male nudity was embraced in Archaic sculpture because men’s bodies were celebrated as objects of beauty and strength, female nudity was still considered inappropriate and immodest. Although kouroi and korai all have these basic traits, their appearances vary depending on when and where they were made.

Just as today’s beauty ideals differ between countries, different regions of the Greek world preferred different types of kouroi. On Samos, an East Greek island with an important sanctuary dedicated to Hera, kouroi were rounded and smooth. A colossal kouros dedicated in Hera’s sanctuary demonstrates these preferences. Standing more than 15 feet tall, this statue has a fleshy body with no indication of individually defined muscles or bones. Its sculptor carved it so that the veins in the marble compliment the body’s curves, emphasizing its roundness, wide eyes, and bulky bodies.

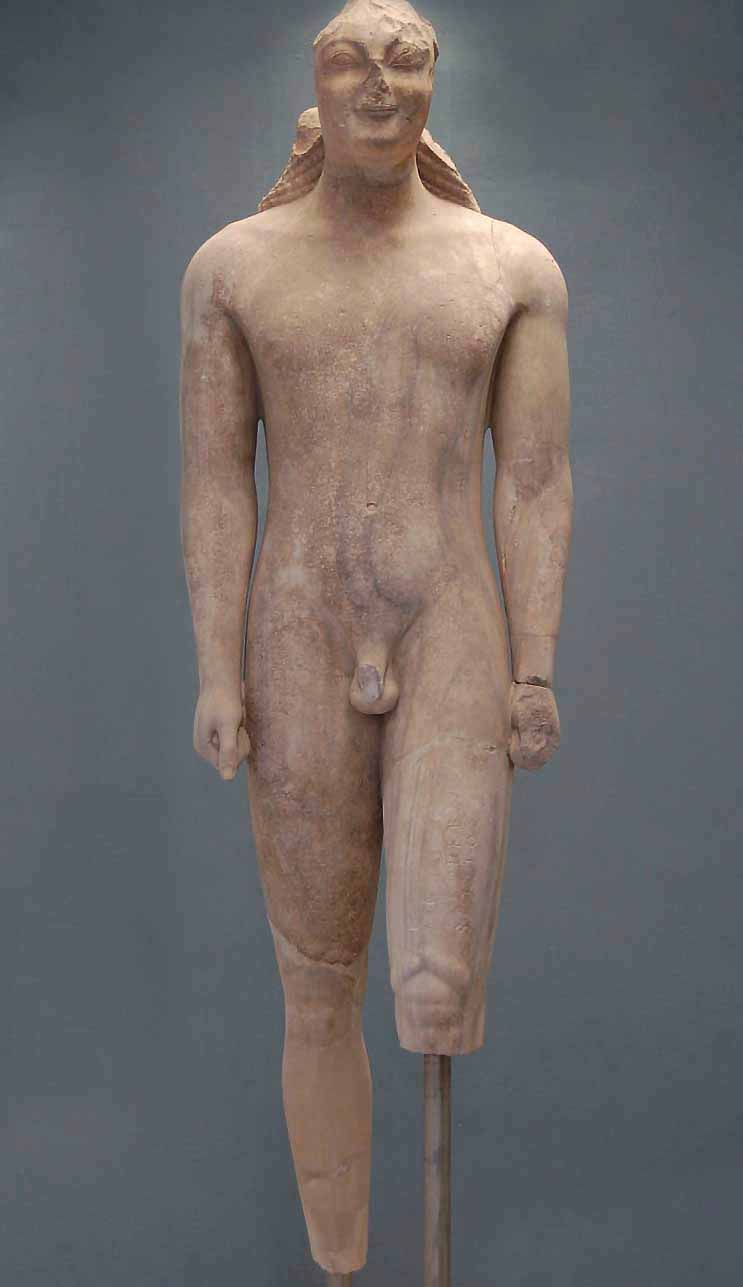

Marble Statue of a Kouros (New York Kouros, from Attica), c. 590–580 B.C.E. (Attic, Archaic), Naxian marble, 194.6 x 51.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

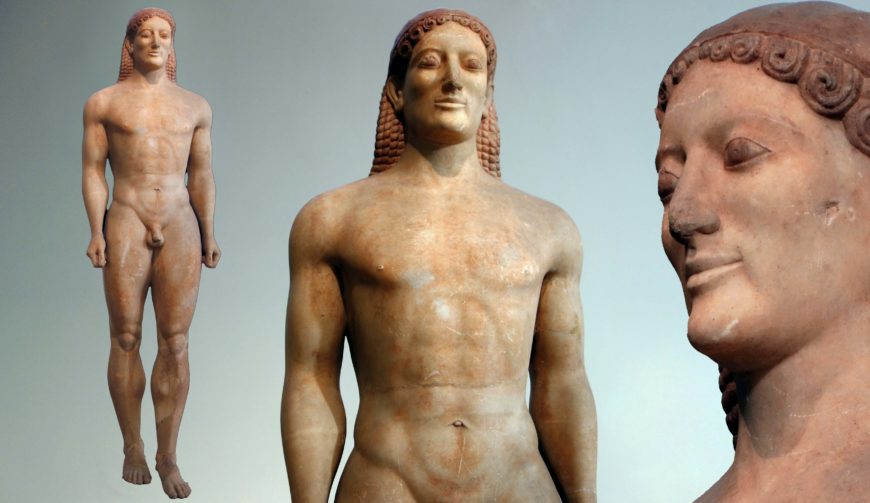

In contrast, Athenians preferred kouroi with slender bodies, lean muscles, and large heads, like the New York Kouros. Attic kouroi changed over time, becoming more naturalistic as sculptors grew more comfortable working with marble and patrons’ tastes changed. The Anavysos Kouros, made some 50 years after the New York Kouros, has a more realistic face than its predecessor. The later kouros (the Anavysos Kouros) has a wider body that more closely resembles that of an actual man. Although the Anayvsos Kouros is more developed than the New York Kouros, it still has rigid posture, intricately braided hair, and an Archaic smile.

Anavysos (Kroisos) Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6′ 4″ (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Attic korai also evolved during the sixth century B.C.E. The earliest kore dedicated on the Athenian Acropolis is today called the Pomegranate Kore because she holds a pomegranate in her left hand. Her costume is relatively simple, hanging from her body in straight lines, though it would have been more elaborate in antiquity when it was painted. Sometime after this kore was made, Athenian sculptors changed the costumes of their korai to look more like those worn by East Greek korai (such as the kore from the Heraion of Samos), who sport intricately folded garments draped diagonally across their upper bodies. This change reflects the shifting fashion preferences of Athenians in the Archaic period.

By 530 B.C.E., Athenian korai wore pleated, East Greek style cloaks over their dresses, as we can see on a kore made by the artist Antenor. This later kore has a slightly more active posture than her predecessors and her body is more visible beneath her gown. Like the Anavysos Kouros, Antenor’s kore is more naturalistic than the korai made before her, but she is still easily recognizable as a kore.

Identifying kouroi and korai

Despite these regional and chronological differences, kouroi and korai generally resemble one another and were immensely popular throughout the Archaic period. What did ancient Greeks use them for, and who did they represent?

When kouroi and korai acted as grave markers, they usually represented the dead person whose grave they marked. They were not realistic depictions of the dead, but instead showed an idealized version of the person they commemorated. The statue’s identity would only be recognizable because of the inscription that accompanied it, usually on its base but sometimes on its clothes or body. Today, many kouroi and korai are found without their bases, making it harder for archaeologists to determine who they honored. We do know that the Anavysos Kouros marked the grave of a man named Kroisos because of the inscription on its base. The statue commemorates Kroisos in what Greeks believed to be the most perfect state, on the cusp of manhood, creating the most ideal memory possible.

Aristion of Paros, Phrasikleia Kore, 550–530 B.C.E., Parian marble and polychromy, 211 cm (National Archaeological Museum of Athens; photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Funerary korai like the Phrasikleia Kore, a particularly well-preserved statue made between 550 and 530 B.C.E., served similar functions. The inscription on the base of this kore identifies the deceased as Phrasikleia, a maiden who died before she was able to marry. The kore is an image of a perfect young Athenian woman. Much of the red paint on her gown survives, and it is incised with ornamental rosettes and meander patterns. She holds a lotus bud in her left hand, wears lotus bud earrings, and sports a lotus crown. The lotus was a symbol of maidenhood, and its multiple appearances on this kore remind us of Phrasikleia’s youth and the tragedy of her death.

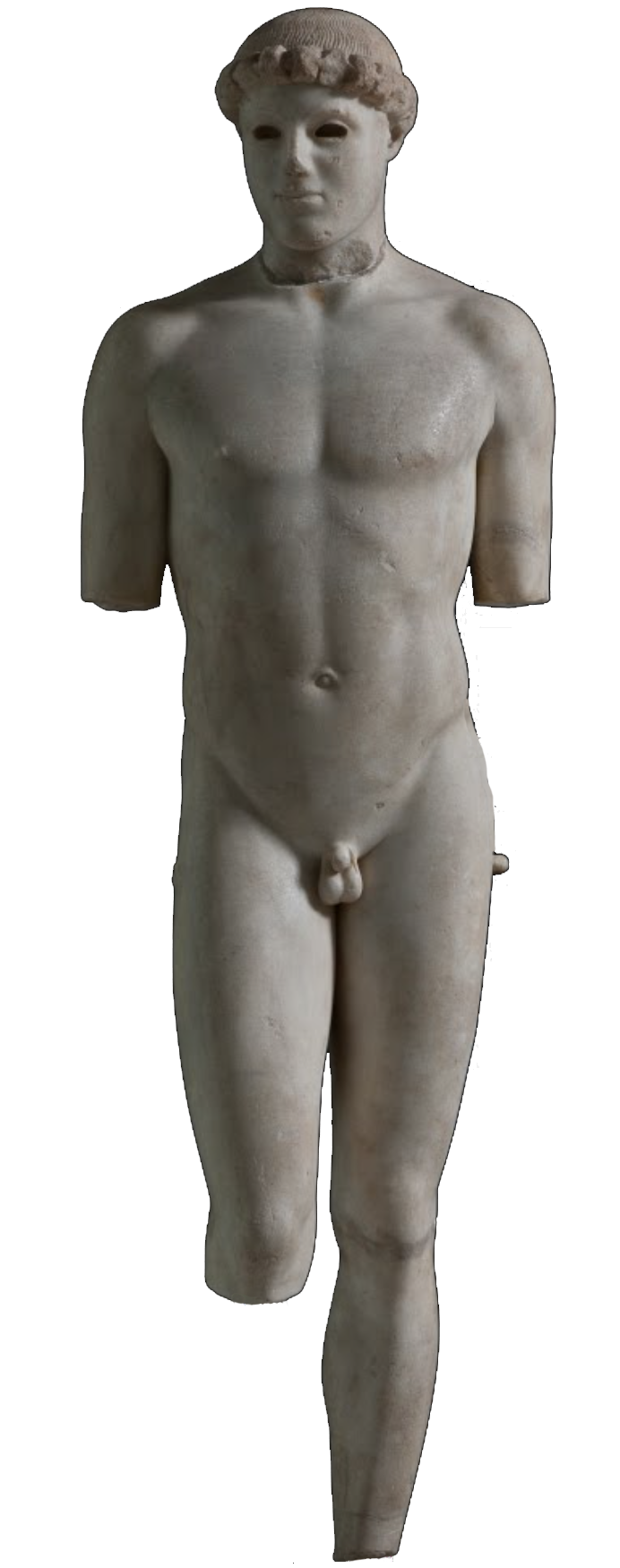

Peplos Kore, c. 530 B.C.E., Paros marble, polychromy, 120 cm (Acropolis Museum)

It is more difficult to determine the identities of the kouroi and korai that were set up in sanctuaries as offerings to the gods. People dedicated these statues to demonstrate their devotion to the gods. Some made their offerings in hopes of securing the protection or approval of the gods, while others dedicated the statues as thank-you gifts in exchange for something they believed the gods had done for them. Like their funerary counterparts, these votive kouroi and korai were often accompanied by inscriptions, but these texts identify the dedicator rather than who the statues represent. It is unlikely that votive kouroi and korai depicted the people who dedicated them because some inscriptions show that men dedicated korai.

Some kouroi and korai may have represented the deities to whom they were dedicated, but we can only securely identify them if they carry attributes. For example, the Peplos Kore, which is just one of dozens of korai that were dedicated to Athena on the Athenian Acropolis, may represent Athena. She wears an unusual costume that sets her apart from other korai, but because her arms do not survive, we can’t tell whether she held the goddess’s attributes. This kore and others like her might instead represent actual young women who served the goddess as attendants. Athenian families could have honored their daughters by dedicating these idealized images to Athena. Just like kouroi, korai were especially expensive and permanent offerings that allowed their dedicators to show off their wealth and devotion to the gods at the same time.

The decline of rigidity

Kouroi and korai began to decline in popularity towards the end of the sixth century B.C.E. They were so emblematic of Archaic elite ideals that they likely seemed conservative to viewers after a new, more democratic government came to power in Athens and began shifting focus towards civic (rather than individual) greatness. When the Persian Empire invaded Athens and burned much of the Acropolis to the ground in 480 B.C.E., the Archaic period came to a close and kouroi and korai fell out of fashion entirely. After the Persian attack, Athenians carefully buried the damaged korai that once stood on the Acropolis in the sacred ground, disposing of them in a respectful manner. They and their male counterparts were replaced by increasingly realistic images of men and women in dynamic postures. The rigidity of the Archaic period was abandoned, and naturalism became a key artistic trait of the Classical period that followed.

Additional resources:

Learn more about the “Lady of Auxerre”

Learn more about the New York Kouros

Learn more about the Anavysos Kouros

Learn more about the Peplos Kore

Learn more about the kouroi of Kleobis and Biton

William R. Biers, The Archaeology of Greece, 2nd Edition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), especially pp. 165-171.

John Boardman, Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period: A Handbook (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

Jeffrey M. Hurwit, “The Human Figure in Early Greek Sculpture and Vase Painting,” The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece, ed. H. Alan Shapiro (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 265–86.

Katerina Karakasi, Archaic Korai (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003)

Catherine A. Keesling, The Votive Statues of the Athenian Acropolis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Olga Palagia, “Sculpture and Its Role in the City,” The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Athens, eds. Jenifer Neils and Dylan Rogers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), p. 282–92.

John Griffiths Pedley, Greek Art and Archaeology, 5th Edition (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2012), especially pp. 171–87.

Gisela M. A. Richter, Korai: archaic Greek maidens: a study of the development of the Kore type in Greek sculpture (London: Phaidon, 1968).

Gisela M. A. Richter, Kouroi: archaic Greek youths: a study of the development of the Kouros type in Greek sculpture (London: Phaidon, 1970).

Brunilde S. Ridgway, The Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture (Chicago: Ares Publisher, 1993).

Andrew F. Stewart, “When Is a Kouros Not an Apollo? The Tenea ‘Apollo’ Revisited,” Corinthiaca: Studies in Honor of Darrell A. Amyx, eds. Mario A. Del Chiaro and William R. Biers (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1986), p. 54–70.

Andrew F. Stewart, Greek Sculpture: An Exploration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

Andrew F. Stewart, Art, Desire, and the Body in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Mary C. Sturgeon, “Archaic Athens and the Cyclades,” Greek Sculpture: Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods, ed. Olga Palagia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 32–76.