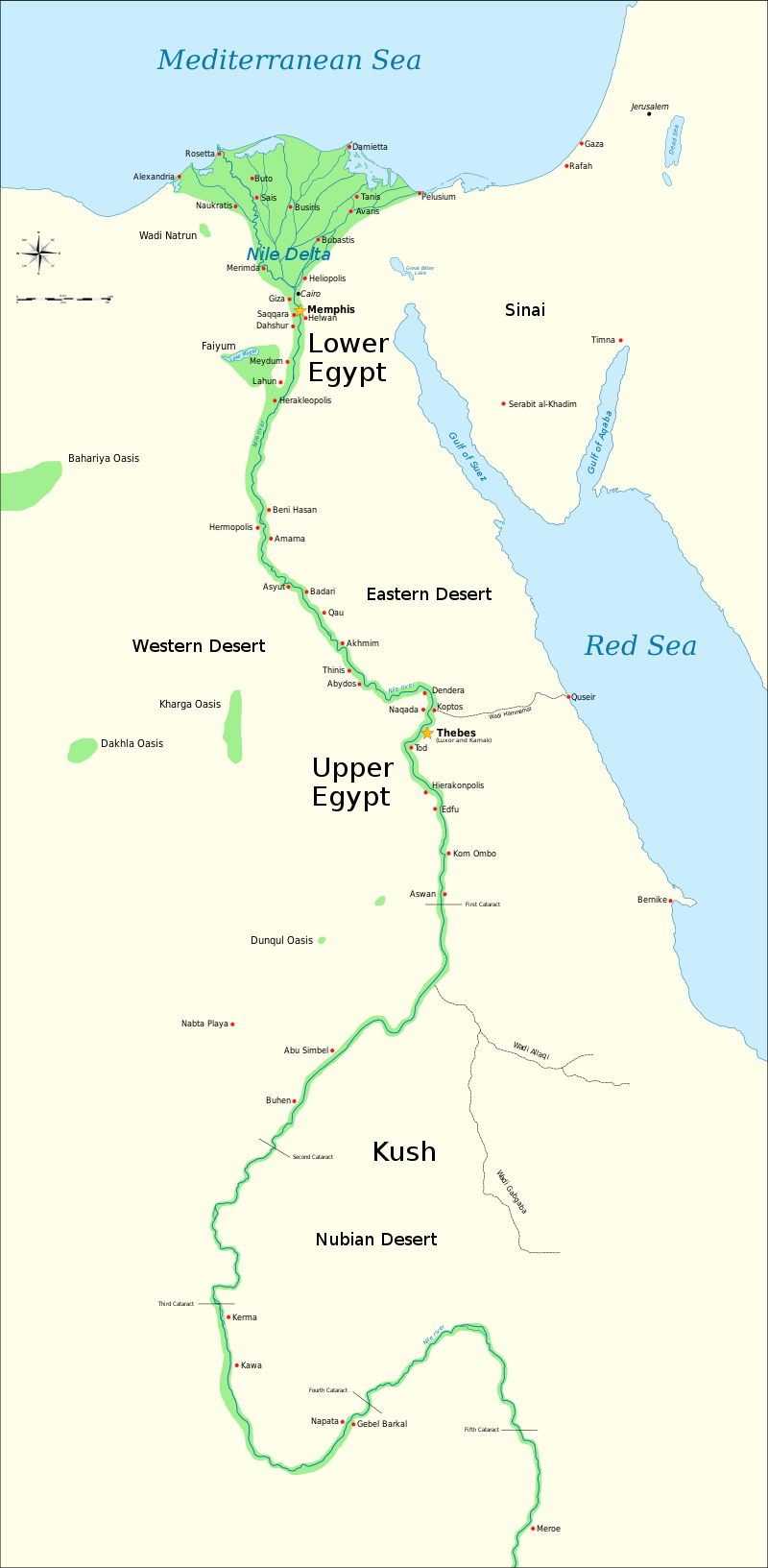

Map of Kush and Ancient Egypt, showing the Nile up to the fifth cataract, and major cities and sites of the ancient Egyptian Dynastic period (c. 3150 BC to 30 BC) (map: Jeff Dahl, CC Y-SA 4.0)

Ancient Sudan: The Meroitic Period (about 300 B.C.E.–350 C.E.)

The Meroitic period, the later phase of rule by the Kushite kings, is named after the royal burial ground at Meroe. In the third century B.C.E. the royal cemetery was moved there from Napata, though Meroe had long been one of the major centers of the Kushite state. This move broadly coincided with the arrival of Greek culture in Egypt, following the country’s conquest by Alexander the Great. The resulting Greco-Egyptian culture rapidly influenced the Kingdom of Kush giving its later phases a distinctive character. This was in contrast to the preceding Napatan period, which was influenced by the Pharaonic culture. The Kushite kingdom prospered, its rulers and the elite deriving wealth from control of the trade routes along the Nile valley from Central Africa to Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt.

Throughout the Meroitic period Egyptian elements introduced into Kushite royal burial practices under the early Napatan kings were retained and reinterpreted. The sculpture and architecture of the period shows much influence from the Greek and the Greco-Roman world. The fine pottery decorated with geometric forms and floral and animal motifs shows a similar influence. Monumental inscriptions were traditionally written in the hieroglyphic script but, from the second century BC onwards, the use of the native language of the Kushite Kingdom, Meroitic, became common. Although some words in Meroitic can be translated, its meaning remains largely unknown to us.

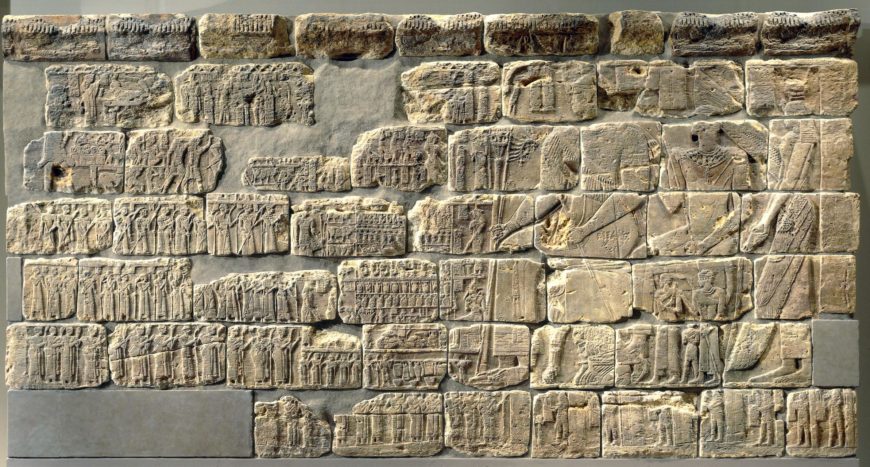

Red sandstone relief from the pyramid chapel of Queen Shanakdakhete, Meroitic Period, 2nd century B.C.E., from Meroe, Central Sudan, 244 x 455.5 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

First female ruler of the Meroitic Period

The royal cemetery at Meroe has given the name ‘Meroitic’ to the later stages of rule by the Kushite kings. The Meroitic script has been deciphered, but the language is still not fully understood. This wall comes from one of the small steep-sided pyramids with chapels in which the rulers were buried. It was probably that of Queen Shanakdakhete, the first female ruler. She appears here enthroned with a prince, and protected by a winged Isis. In front of her are rows of offering bearers and also scenes of rituals including the judgement of the queen before Osiris. Although the reliefs are in a style that looks Egyptian, they have their own, independently developed, characteristics.

The term ‘Kush’ or ‘Kushite’ was used long before the eighth century B.C.E. to refer to Nubian ruling powers. But it is particularly used to describe the cultures whose first major contact with Egypt began with the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, and whose Nubian kings put an end to the fragmented state of Egypt by 715 B.C.E. However, Kushite rule did not last long in Egypt. In the face of Assyrian attack, the last Kushite kings, Taharqa and Tanutamun, fled to Nubia. There they and their descendants were dominant until the fourth century C.E., and were buried at el-Kurru, Nuri, Gebel Barkal, and Meroe.

Sandstone ba statue of a woman, Meroitic Period, 2nd century C.E., from Egypt, 45.8 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The spirit of a wealthy woman

The Egyptians believed that a person’s essence or soul was composed of several elements. These became separated at death. The ba was one of the elements of the spirit, which encompassed the personality and emotions. It stayed close to the body of the deceased and was eventually reunited with other elements, to live eternally in the Afterlife.

In Egyptian art, the ba is chiefly represented on funerary papyri. These representations were intended to enable the deceased’s entry into the Afterlife. In a funerary context, the ba in its form of a human-headed bird was retained in the Meroitic period. However, the style, the material used, and the location of representations was entirely different from earlier depictions. A stone statue like this one would have been placed outside the tomb chapel of a wealthy individual, in this case a woman.

The reduction of the body to its essential details perhaps reflects a continental African influence. This example shows the ba in a female human form, wearing a long dress, but with wings instead of arms. The emphasis on the eyes is typical of later Meroitic sculpture, but the Egyptian origins of the statue can be seen in their almond shape and heavy outline.

Sandstone offering table of Malewitar, Meroitic Period, 1st–2nd centuries C.E., from Faras, Sudan (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Offering tables with Meroitic script

Meroitic offering tables tend to be roughly square in shape, with a central depression for holding liquids. Some examples, such as this, bear representations of the food which would be placed on the table, while others have figured decoration. Around the outside is an inscription which names of the owner and gives his parentage.

The Meroitic language is written in two scripts, one derived from hieroglyphs and the other a more cursive form, as here. Although the sound-values of the signs are known, insufficient material for comparison, especially bilingual inscriptions or related languages that are understood, has been found to enable the language to be analyzed or translated properly. Thus names can mostly be read, but the longer inscriptions largely defy interpretation.

Fineware painted cups, Meroitic Period, 1st to 2nd century C.E., from Faras, Sudan (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Fineware vessels

Meroitic graves often included fragile bowls, jars and cups. The fine quality of the manufacture and decoration of these vessels suggests that they were the prized possessions of the deceased, who wanted to continue to enjoy them in the Afterlife.

Although the vessels themselves were of local manufacture, the designs were often inspired by the artistic traditions of other countries, such as Egypt and the Mediterranean world. Symbols such as the ankh were borrowed from Egypt, as were the lotus and papyrus plants. Although still recognizable, the Meroitic artists interpreted them in their own way, often producing a geometric pattern, which would be unfamiliar to their Egyptian counterparts.

Other motifs, such as animals like frogs, snakes and fantastic beasts, were drawn from the Mediterranean world. The origin of the boat design on this cup is less clear. The tall prow and stern of the vessel, and the stick figure inside is reminiscent of the decoration of Egyptian pots in the Predynastic period, three thousand years earlier. The resemblance ends here though, and is purely coincidental.

Red slipped amphora decorated with vine leaves and ducks in black and white, Meroitic Period, 1st to 2nd centuries C.E., from Faras, Sudan, 43 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

A transcultural amphora

Fineware bowls, cups and jars were often placed in Meroitic graves, to be used by the deceased in the Afterlife. Like the fragile fineware vessels, this amphora is covered in a red slip upon which the painted decoration is applied in bands, using a basic palette of black, red and white. A picture of the vessel itself appears on the neck of the amphora.

The decorative motifs are derived from those of Ptolemaic and early Roman Egypt, from about the third to the first century B.C.E. The combination of geometric, floral and animal motifs is typical of pottery of this period. It shows the influence of the Mediterranean world, which was becoming ever more pronounced as Egypt came under the domination of the Greeks, and then the Romans. The running vine leaves continued to be a popular motif into the Coptic period, appearing on pottery until the Arab conquest in the seventh century C.E.

Animal motifs were common in the art of the Mediterranean world. The ducks at the base of this vessel could have been observed from local wildlife. They could also be derived from Egyptian art, in which they were frequently depicted, or copied from hieroglyphic symbols.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources:

J.H. Taylor, Egypt and Nubia (London, The British Museum Press, 1991)

F. Ll. Griffith, ‘Meroitic funerary inscriptions from Faras, Nubia’ in Receuil détudes égyptologiques (Paris, 1922)