The Great Ziggurat of Ur has been reconstructed twice, in antiquity and in the 1980s—what’s left of the original?

Ziggurat of Ur (largely reconstructed), c. 2100 B.C.E., mud brick and baked brick, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq (photo: Tla2006)

The Great Ziggurat

The ziggurat is the most distinctive architectural invention of the Ancient Near East. Like an ancient Egyptian pyramid, an ancient Near Eastern ziggurat has four sides and rises up to the realm of the gods. However, unlike Egyptian pyramids, the exterior of ziggurats were not smooth but tiered to accommodate the work which took place at the structure, as well as the administrative oversight and religious rituals essential to Ancient Near Eastern cities. Ziggurats are found scattered around what is today Iraq and Iran, and stand as an imposing testament to the power and skill of the ancient culture that produced them.

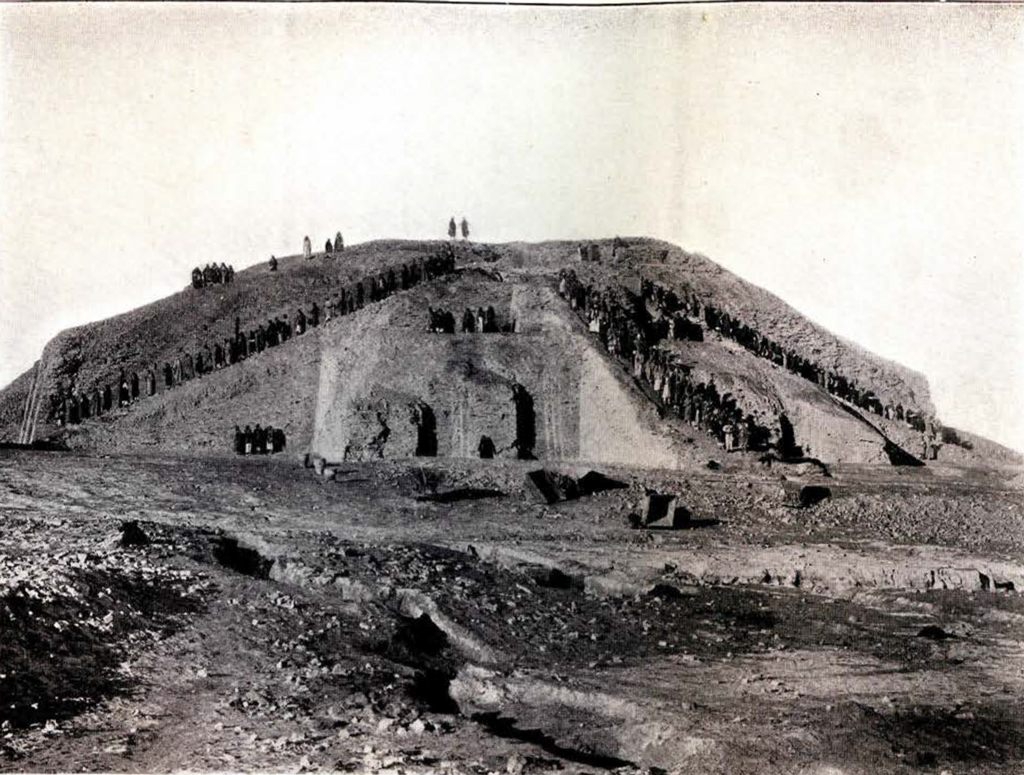

One of the largest and best-preserved ziggurats of Mesopotamia is the Great Ziggurat at Ur. Small excavations occurred at the site around the turn of the twentieth century, and in the 1920s Sir Leonard Woolley, in a joint project with the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum in London, revealed the monument in its entirety.

Leonard Woolley, photo with excavation workers, c. 1923–24, featuring the ziggurat of Ur, c. 2100 B.C.E., Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq (photo: Penn Museum, Philadelphia)

What Woolley found was a massive rectangular pyramidal structure, oriented to true north, 210 x 150 feet (64 x 46 meters), constructed with three levels of terraces, standing originally between 70 x 100 feet (21 x 30 meters) high. Three monumental staircases led up to a gate at the first terrace level. Next, a single staircase rose to a second terrace which supported a platform on which a temple and the final and highest terrace stood. The core of the ziggurat is made of mud brick covered with baked bricks laid with bitumen, a naturally occurring tar. Each of the baked bricks measured about 11.5 x 11.5 x 2.75 inches (29 x 29 x 7 cm) and weighed as much as 33 pounds. The lower portion of the ziggurat, which supported the first terrace, would have used some 720,000 baked bricks. The resources needed to build the ziggurat at Ur are staggering.

Ziggurat of Ur (largely reconstructed), c. 2100 B.C.E., mud brick and baked brick, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq (photo: Kaufingdude, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Moon goddess Nanna

The ziggurat at Ur and the temple on its top were built around 2100 B.C.E. by the king Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur for the moon goddess Nanna, the divine patron of the city state. The structure would have been the highest point in the city by far and, like the spire of a medieval cathedral, would have been visible for miles around, a focal point for travelers and the pious alike. As the ziggurat supported the temple of the patron god of the city of Ur, it is likely that it was the place where the citizens of Ur would bring agricultural surplus and where they would go to receive their regular food allotments. In antiquity, to visit the ziggurat at Ur was to seek both spiritual and physical nourishment.

Ziggurat at Ali Air Base Iraq, 2005, featuring ziggurat of Ur, partly restored, c. 2100 B.C.E. mudbrick and baked brick, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq

Clearly the most important part of the ziggurat at Ur was the Nanna temple at its top, but this, unfortunately, has not survived. Some blue glazed bricks have been found which archaeologists suspect might have been part of the temple decoration. The lower parts of the ziggurat, which do survive, include amazing details of engineering and design. For instance, because the unbaked mud brick core of the temple would, according to the season, be alternatively more or less damp, the architects included holes through the baked exterior layer of the temple allowing water to evaporate from its core. Additionally, drains were built into the ziggurat’s terraces to carry away the winter rains.

U.S. soldiers descend the ziggurat of Ur, 2009, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq (photo: United States Forces Iraq, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Hussein’s assumption

The ziggurat at Ur has been restored twice. The first restoration was in antiquity. The last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabodinus, apparently replaced the two upper terraces of the structure in the 6th century B.C.E. Some 2,400 years later in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein restored the façade of the massive lower foundation of the ziggurat, including the three monumental staircases leading up to the gate at the first terrace. Since this most recent restoration, however, the ziggurat at Ur has experienced some damage. During the recent war led by American and coalition forces, Saddam Hussein parked his MiG fighter jets next to the ziggurat, believing that the bombers would spare them for fear of destroying the ancient site. Hussein’s assumptions proved only partially true as the ziggurat sustained some damage from American and coalition bombardment.

Additional resources

Read a Reframing Art History textbook chapter about rethinking approaches to the art of the Ancient Near East.