Elaborate funerary rituals

Etruscan civilization, 750–500 B.C.E. (image: NormanEinstein, CC BY-SA 3.0) Based on a map from The National Geographic Magazine Vol.173 No.6 (June 1988)

Funerary contexts constitute the most abundant archaeological evidence for the Etruscan civilization. The elite members of Etruscan society participated in elaborate funerary rituals that varied and changed according to both geography and time.

The city of Tarquinia (known in antiquity as Tarquinii or Tarch(u)na), one of the most powerful and prominent Etruscan centers, is known for its painted chamber tombs. The Tomb of the Triclinium belongs to this group and its wall paintings reveal important information about not only Etruscan funeral culture but also about the society of the living.

An advanced Iron Age culture, the Etruscans amassed wealth based on Italy’s natural resources (particularly metal and mineral ores) that they exchanged through medium- and long-range trade networks.

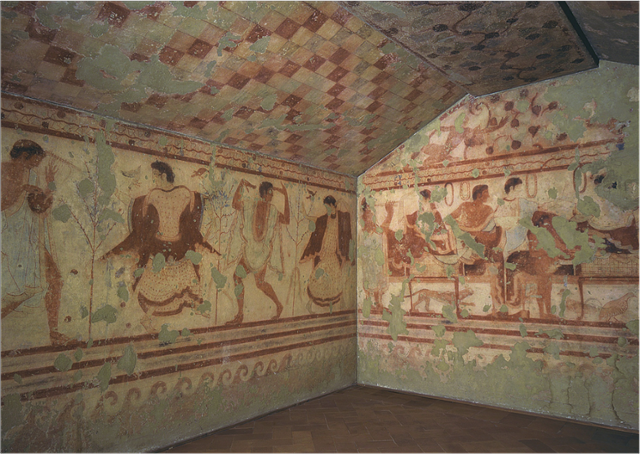

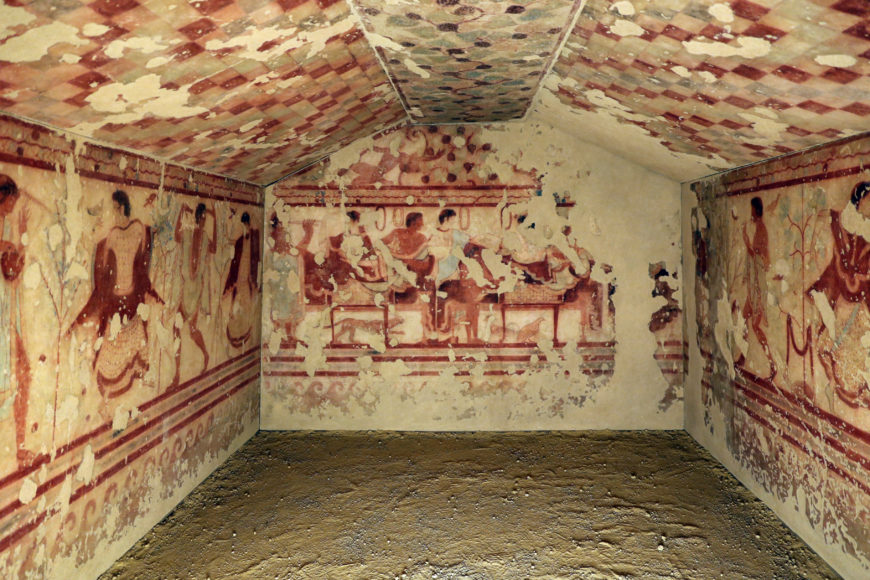

Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Tomb of the Triclinium

The Tomb of the Triclinium (Italian: Tomba del Triclinio) is the name given to an Etruscan chamber tomb dating c. 470 B.C.E. and located in the Monterozzi necropolis of Tarquinia, Italy. Chamber tombs are subterranean rock-cut chambers accessed by an approach way (dromos) in many cases. The tombs are intended to contain not only the remains of the deceased but also various grave goods or offerings deposited along with the deceased. The Tomb of the Triclinium is composed of a single chamber with wall decorations painted in fresco. Discovered in 1830, the tomb takes its name from the three-couch dining room of the ancient Greco-Roman Mediterranean, known as the triclinium.

A banquet

The rear wall of the tomb carries the main scene, one of banqueters enjoying a dinner party (above). It is possible to draw stylistic comparisons between this painted scene that includes figures reclining on dining couches (klinai) and the contemporary fifth century B.C.E. Attic pottery that the Etruscans imported from Greece. The original fresco is only partially preserved; although it is likely that there were originally three couches, each hosting a pair of reclining diners, one male and one female. Two attendants—one male, one female—attend to the needs of the diners. The diners are dressed in bright and sumptuous robes, befitting their presumed elite status. Beneath the couches we can observe a large cat, as well as a large rooster and another bird.

Barbiton player on the left wall (detail), Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy

Music and dancing

Scenes of dancers occupy the flanking left and right walls. The left wall scene contains four dancers—three female and one male—and a male musician playing the barbiton, an ancient stringed instrument similar to the lyre.

Common painterly conventions of gender typing are employed—the skin of females is light in color while male skin is tinted a darker tone of orange-brown. The dancers and musicians, together with the feasting, suggest the overall convivial tone of the Etruscan funeral. In keeping with ancient Mediterranean customs, funerals were often accompanied by games, as famously represented by the funeral games of the Trojan Anchises as described in book 5 of Vergil’s epic poem, the Aeneid. In the Tomb of the Triclinium we may have an allusion to games as the walls flanking the tomb’s entrance bear scenes of youths dismounting horses, variously described as being either apobates (participants in an equestrian combat sport) or the Dioscuri (mythological twins).

Two dancers on the right wall (detail), Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy

The tomb’s ceiling is painted in a checkered scheme of alternating colors, perhaps meant to evoke the temporary fabric tents that were erected near the tomb for the actual celebration of the funeral banquet.

The actual paintings were removed from the tomb in 1949 and are conserved in the Museo Nazionale in Tarquinia. As their state of preservation has deteriorated, watercolors made at the time of discovery have proven very important for the study of the tomb.

Interpretation

The convivial theme of the Tomb of the Triclinium might seem surprising in a funereal context, but it is important to note that the Etruscan funeral rites were not somber but festive, with the aim of sharing a final meal with the deceased as the latter transitioned to the afterlife. This ritual feasting served several purposes in social terms. At its most basic level the funeral banquet marked the transition of the deceased from the world of the living to that of the dead; the banquet that accompanied the burial marked this transition and ritually included the spirit of the deceased, as a portion of the meal, along with the appropriate dishes and utensils for eating and drinking, would then be deposited in the tomb. Another purpose of the funeral meal, games, and other activities was to reinforce the socio-economic position of the deceased person and his/her family: a way to remind the community of the living of the importance and standing of these people and thus tangibly reinforce their position in contemporary society. This would include, where appropriate, visual reminders of socio-political status, including indications of wealth and civic achievements, notably public offices held by the deceased.