Visitors to Knossos, 2016, photo: Neil Howard, CC BY-NC 2.0

There aren’t many places in the world like Knossos. Situated 6km south of the sea, on the north central coast of Crete, several things make this archaeological site important: its great antiquity (it is 9,000 years old), many different cultural layers (Neolithic through Byzantine), its size (nearly 10 square Km) and its great popularity (the second most visited archaeological site in Greece after the Acropolis at Athens). Aside from these, however, Knossos is also exceptional because of its role in the writing of history. It is the type site for all of Minoan archaeology, was one of the first large-scale scientific excavations in Europe, and contains some of the most contentious restorations in the ancient Mediterranean. Because of all this, Knossos is a critical part of multiple discourses in the history and historiography of the ancient world. We can’t stop talking about Knossos.

Throne Room, Knossos (photo: Olaf Bausch, CC BY 3.0)

A palace?

Bronze Age Knossos is traditionally called a palace, a description used by its most famous excavator, Sir Arthur Evans. Indeed, when Evans, just three weeks after beginning his work at the site, discovered a grandly paved and painted room with a large stone chair set in the wall he believed he had found the throne of Minos and the kings of Crete. This royal interpretation of the site of Knossos stuck. Although it is now clear that the role of Knossos was at least as religious and economic as it was political, it is still just called a palace.

The archaeological site at Knossos, with restored rooms in the background, Crete (photo: Jebulon, public domain)

Early Knossos

The site of Knossos was first inhabited around 7000 B.C.E. and was one of the earliest Neolithic sites in the Mediterranean, settled at a time when pottery had yet to be invented. It continued to be a well-populated site for successive Neolithic eras, one literally building upon another, eventually creating one of the only tell sites of the Aegean, nearly 100 meters above sea level. Unfortunately, not a lot is known about Neolithic Knossos as the Bronze Age inhabitants entirely covered over its remains with their own structures. However, limited excavations show that it was one of the oldest farming villages in Europe which had connections to even earlier Mesolithic inhabitants elsewhere on the island.

Before the palace

The end of the 4th millennium B.C.E. is the beginning of the early Bronze Age at Knossos, a time when the inhabitants learned how to combine tin and copper to make bronze tools and weapons, far more durable than their stone predecessors. Although the palace structure is yet to come, already the buildings on the site have a north-south orientation, as the palace eventually will. Moreover, it appears that ceremonial activity was already common at this time, evidenced by so many specially made and decorated drinking cups. Approximately 1,000 years later, around the end of the 3rd millennium B.C.E., the first large-scale buildings were built at Knossos. The nature and shape of these structures are very difficult to ascertain because the later palace largely obscures them, but already the outline of the large (49 x 27m) rectangular open central court is established.

Standing in the central court today

Protopalatial or Old Palace Knossos

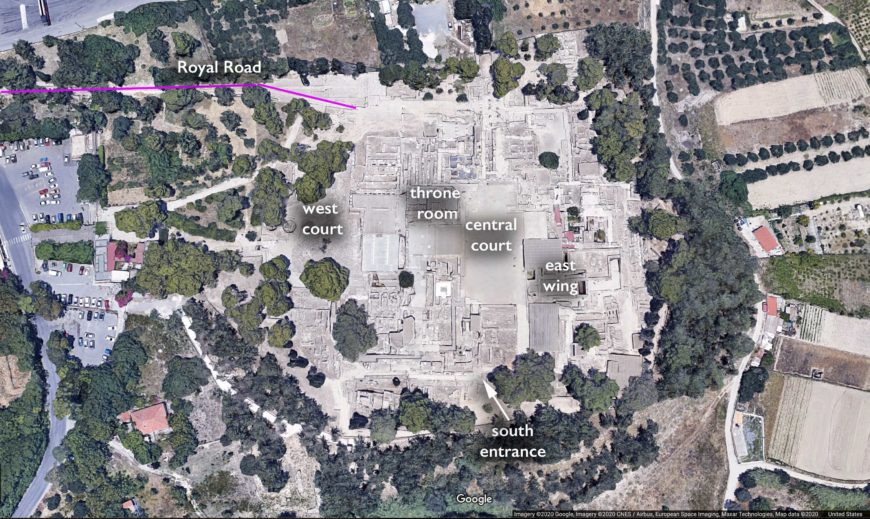

Approximately two hundred years later, at the start of the 2nd millennium (around 1950–1800 B.C.E.) the outline and dimensions of the palace of Knossos emerges and begins what is called the Protopalatial or Old Palace period. The two most distinctive features of this earliest version of Knossos are the long, monumental, cut ashlar stone of the palace’s west façade and the central court, now squared off in the corners and paved. This court functioned as a grand performance space. In this period, a wide paved road, which Evans named the Royal Road, is built. The road connects Knossos to the adjacent town to the west. An entrance system of raised walkways is also built at this time.

Kouloures, or circular stone-lined and plastered pits, Protopalatial Knossos (left photo: C messier, CC BY-SA 4.0; right photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

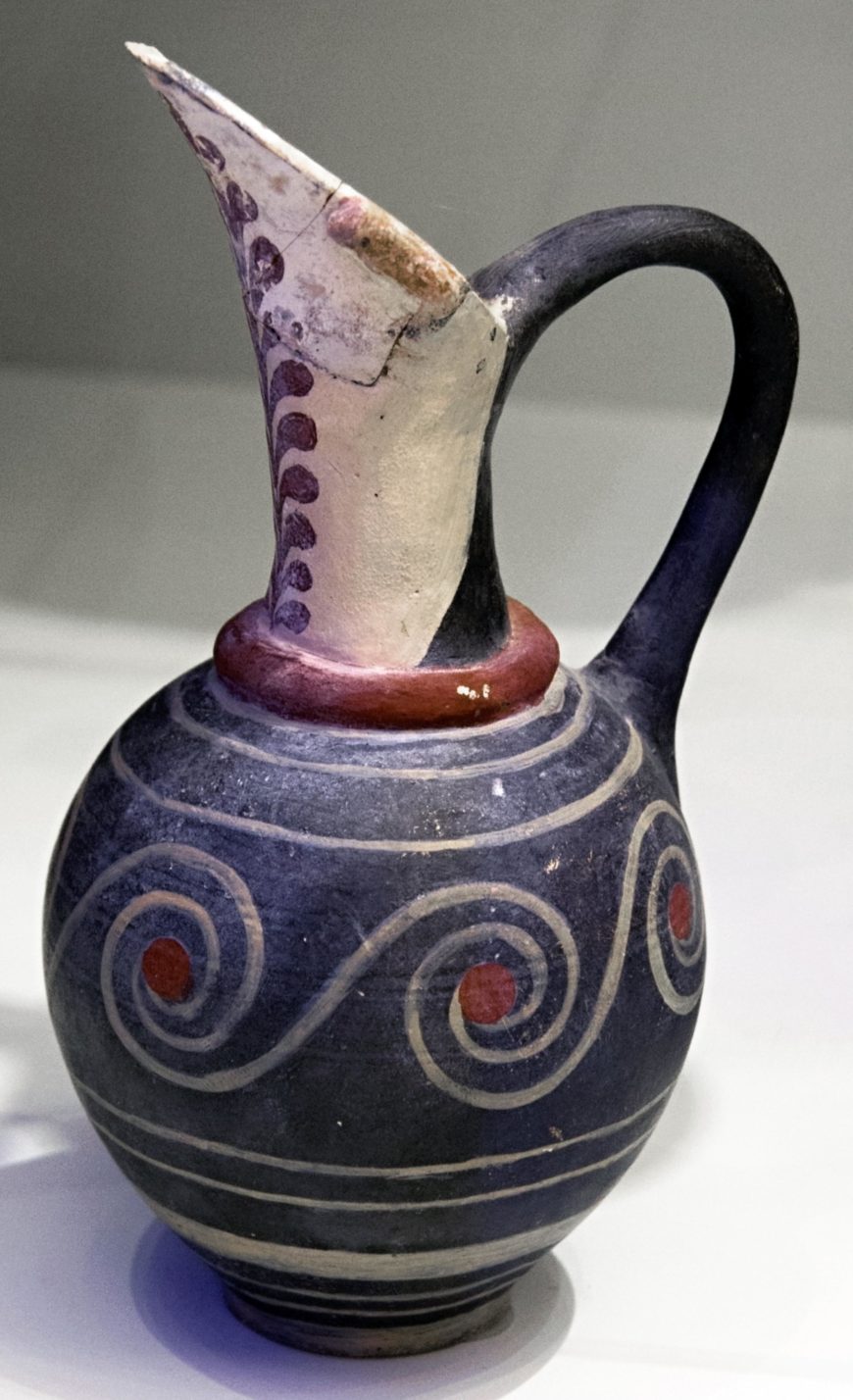

Kamares Ware vessel from Knossos, 1800–1700 B.C.E. (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion; photo: Zde)

It is clear that, like contemporary ancient Near Eastern temples, storage was an important aspect of Protopalatial Knossos. Long thin storage rooms to the west of the central court are built at this time. In addition, sunk into the open court to the west of the palace were large, deep, circular pits lined with plastered stone, called Kouloures, which archaeologist believe stored grain.

Protopalatial Knossos stored more that raw materials, it also produced finished goods. There is evidence of seal stone carving, weaving, and pottery production (especially Kamares Ware) and likely gold working as well. In this busy place, a written script, Cretan Hieroglyphic, was used to keep records, written on clay tablets and nodules which were attached to containers of goods. As of yet, the language this script recorded has not been translated.

South Propylaeum, Knossos (photo: Stegop, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Neopalatial or New Palace Knossos

Around 1700 B.C.E. major renovations are undertaken at Knossos, likely the result of a destructive event, possibly an earthquake. These renovations mark the beginning of the Neopalatial or New Palace period and result in the most characteristic elements of Knossos: the West Court is paved (made by filling in the Protopalatial Kouloures) to be used for public ceremonies, the monumental south entrance (or South Propylaeum) is added to impress visitors.

“Queen’s megaron,” East Wing, Knossos (photo: Andy Montgomery, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Throne Room with its lustral basin or light well is built to comfortably accommodate the leadership of the palace, and the elegant spaces of the East Wing or Domestic Quarter are constructed, where Evans believed the queen of Knossos passed her time.

Blue monkey frieze, c. 1580–1530 B.C.E, fresco, found in the House of the Frescoes, room D (today in the Heraklion, Archaeological Museum, Crete; photo: ArchaiOptix)

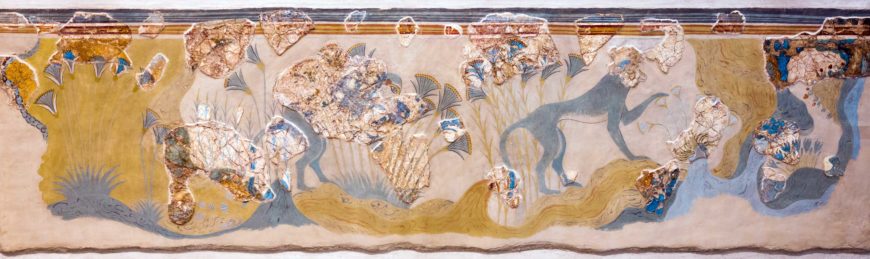

These new spaces were replete with innovative architectural details including colonnaded staircases, light wells, pier and door partitions, and wall and floor paintings. This was a grand era for painting at Knossos. There were beautiful scenes of the natural world, such as in the Blue Monkey or Partridge Frieze frescoes, as well as miniature scale works such as the Grandstand Fresco, which seems to represent group performances in the West Court.

Contemporary view of Knossos looking southwest from the Monumental North Entrance (photo: Theofanis Ampatzidis, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Raging bull, Monumental North Entrance, Knossos (photo: Hannes Hiller, CC BY 2.0)

The monumental North Entrance passage was rebuilt in the Neopalatial period and decorated with a relief wall painting of a raging bull, an image which becomes emblematic of Knossos and Minoan Crete. Pottery production reaches new heights, most famously in the delightful marine style, which some archaeologists believe is a reflection of a Minoan thalassocracy (sea power).

Innovation in the Neopalatial period extends to writing as well: a new script, in addition to Cretan Hieroglyphic, is used at Neopalatial Knossos, Linear A. Although this script also remains largely unreadable, it is clear that it was used for accounting and administration, noting the movement of materials and people between the palace and sites across the island. It also reflects the way in which Knossos and a number of other smaller sites which look very similar to Knossos, and are also called palaces (Malia, Phaistos, Zakros, Monastiraki, Petras, Chania and Galatas) were a focal point for much of the population and labour on Crete at the time. This palatial network not only connected Cretan communities but also maintained trading ties with the Eastern Mediterranean.

Throne Room with griffins in the frescos on the wall, Knossos (photo: Olaf Bausch, CC BY 3.0)

Postpalatial or Final Palatial Knossos

There are signs that the palace suffered a series of destructions around 1450 B.C.E., at the same time that there are widespread destructions and abandonment of Minoan sites all over Crete. These events begin what is called the Postpalatial or Final Palatial period, which lasts approximately 150 years. Knossos is rebuilt after these destructions but differently. For instance, no more lavish limestone ashlar masonry was cut for the exterior of the palace and new interior walls were erected to change the flow of movement, seemingly to cut off certain areas, such as the West magazines (storage areas), presumably for security. Most importantly, the Throne Room was redesigned in this era to include the griffins seen in the archaeological reconstruction and possibly for the installation of the throne itself.

Bull-leaping fresco from the east wing of the palace of Knossos (reconstructed), c. 1400 B.C.E., fresco, 78 cm high (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Jebulon, CC0)

Much of the palace interior was repainted in this Postpalatial era and this includes many of the most famous wall paintings from Knossos: the bull leaping or Toreador fresco, the Procession fresco, and the Camp Stool fresco. Pottery produced at Postpalatial Knossos is called Palace Style and is based on Neopalatial predecessors but with a quirky kind of stylization which renders subjects less naturalistic and more pattern-like. Some new pottery shapes are created which appear in imitation of mainland Mycenaean pieces.

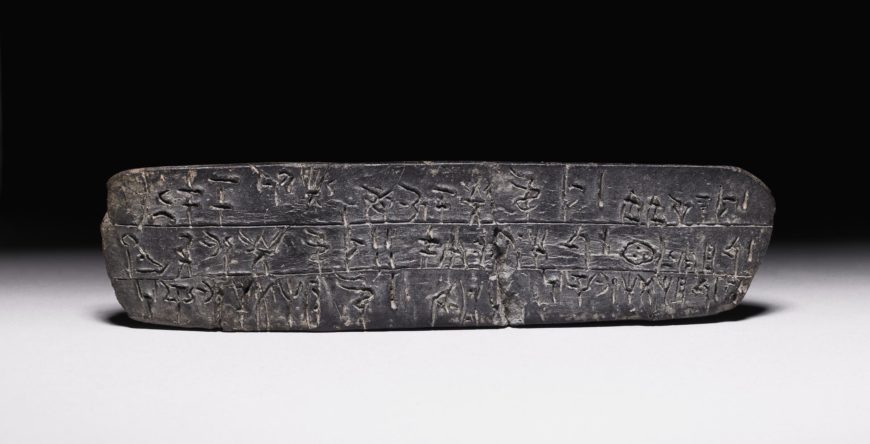

Tablet with Linear B script (describes oil offered to deities and religious officials), c. 1375 B.C.E., Late Minoan IIIA, Knossos, Crete (The British Museum, photo: Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Postpalatial Knossos is still a place of very complex administration as is described by the hundreds of clay tablets discovered. However, the Linear A script is no longer used; it is replaced by Linear B, which can be read, and records a very early form of Classical Greek, the language of the contemporary Mycenaeans of mainland Greece. The social order described in these tablets is that of a Wanax as the leader of Knossos and a deep administration concerned with land tenure, religious activities, and a massive textile industry which employed over 700 shepherds harvesting between 50–75 tons of raw wool, woven by nearly 1,000 workers, men, women, and children, capable of producing some 20,000 individual textile pieces.

Swords (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion; photo: Hyspaosines, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Knossos was clearly a prosperous city in this period and this can also be seen through a new type of burial at the site: warrior graves. These, sometimes extravagantly constructed, tombs of men and women feature a range of fighting weapons such as swords and thrusting daggers, as well as valuable metal vessels and elegant pottery. These sorts of very rich, well-constructed graves are a tradition which is associated with the mainland of Greece.

Cretan and mainland cultures

A lot about Postpalatial Knossos has a distinct Mycenaean flavor and this fact has led many archaeologists to conclude that the destructions at the beginning of the period were actually the Mycenaeans invading the island. However, many Minoan elements remain in Postpalatial culture, and obvious signs of warfare which would have resulted from a large-scale invasion have yet to be found. Therefore, we now like to think of the Postpalatial period at Knossos as one of a hybrid, between Cretan and Mainland cultures, likely created by a local elite who wished to maintain status in both spheres. As to who exactly these local elite were, we have some information. Those buried in warrior graves in the Postpalatial cemeteries around Knossos were born in the region, as recent analysis of skeletal materials has shown. The new Knossian elite did not come from the Mycenaean mainland.

Knossos collapses . . . and rises again

Towards the end of the Postpalatial period Knossos’ status relative to other sites (especially to the south and west) on the island seems to wane. Eventually there is a massive destruction, collapse, and fire at the palace around 1300 B.C.E. From that point there is little reoccupation within the most important parts of the palace, although there is some small-scale reoccupation around its periphery.

Knossos wasn’t down for long. Rapidly after the late Bronze Age collapse a large Early Iron Age settlement emerged north of the palace and was clearly cosmopolitan as it was the only site of the period in Greece with imports ranging from the Middle East to Sardinia. This area eventually develops into a Classical Greek polis (city-state) and in the 1st century B.C.E. suffers Roman conquest. Beautiful mosaics survive from a 2nd century C.E. Roman home, the Villa Dionysos, evidence of the thriving Roman city at the site. A large Christian church is built at the north edge of the site in the 6th century, witness to the Byzantine history of Knossos.