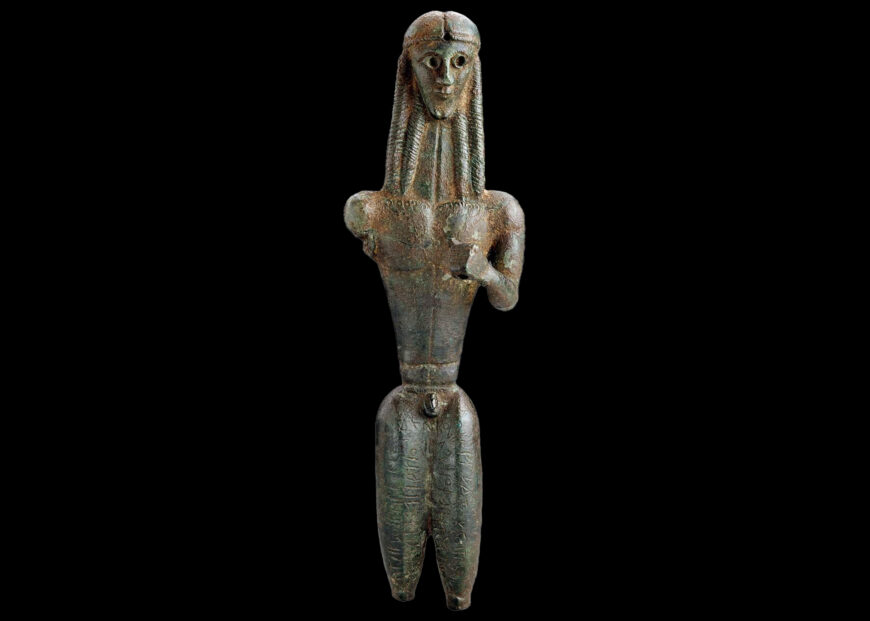

Mantiklos “Apollo,” c. 700–675 B.C.E., bronze, 20.3 cm high (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Meeting Mantiklos

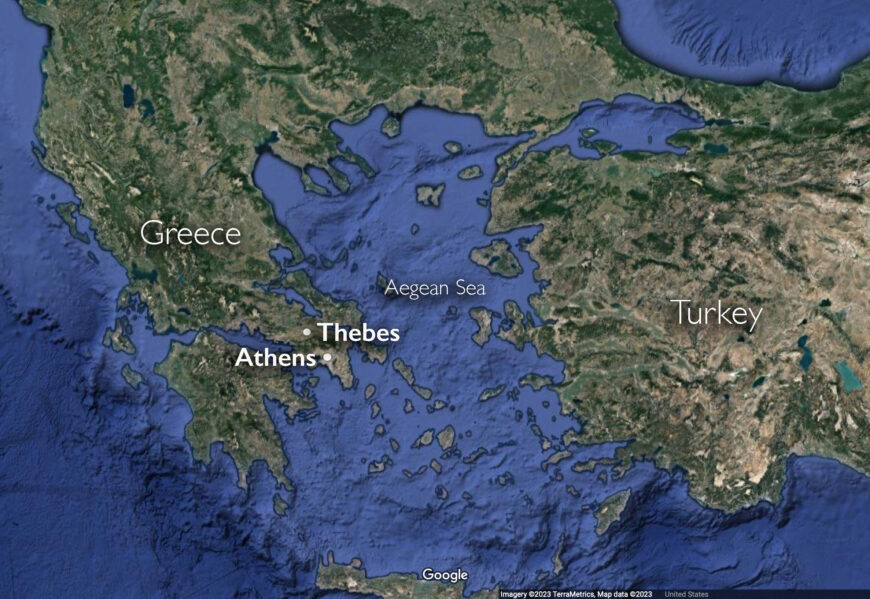

Sometime around 700 B.C.E., a man named Mantiklos gave a gift to one of the many gods he worshiped. Dedicating gifts to the gods was an important practice in ancient Greek religion because worshipers believed such gifts pleased the gods and encouraged them to provide blessings in return. Ancient Greek votive offerings could take many forms. Some devotees gave food or liquid offerings, some gave ceramic vessels, and others gave statues of varying sizes. Mantiklos dedicated a small bronze statue of a male figure to the god Apollo. [1] Modern scholars aren’t sure who the statue represents. The statue’s exact findspot is also unknown, though it is said to be from Thebes, and may have originally been dedicated to Apollo in a sanctuary in that city. [2] Despite these gaps in our knowledge, we know who dedicated this statue (Mantiklos) and who its intended recipient was (Apollo) because of a long inscription on its legs.

Today, Mantiklos’s gift is on display in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In the following paragraphs, we will consider why it is regarded as one of the most important surviving ancient Greek artworks. We’ll first discuss the uncertain identity of the statue, which might represent either Mantiklos or Apollo. We will then discover what the statue’s style reveals about how the ancient Greeks conceived of the ideal human form around 700 B.C.E., when it was made. Then, we’ll consider what the artifact’s inscription tells us about it and the votive function it once fulfilled. Finally, we’ll review how the statue’s form and inscription worked together to please Apollo on behalf of Mantiklos.

An anonymous ideal

The statue that Mantiklos dedicated to Apollo depicts an idealized male figure. While the ideal embodied by this statue might seem unusual to us as modern viewers, it emphasizes the physical traits that were most valued by those who would have seen it shortly after it was made. These traits include rigidity and exaggerated musculature, both of which convey the individual’s strength. The figure is shown mostly nude, so that his body is fully visible. He is now missing his right arm and both of his legs below the knee. He has a triangular face with large eyes, a prominent nose, and a small mouth. His hollow eyes would have originally been inlaid with stone or a precious material. [3] He has long locks of hair that are carefully patterned, almost as if they are braided. This elaborate hairstyle is likely meant to indicate the figure’s wealth. Although he appears to have a central part, there is no patterning on top of his head where we would expect to find more hair. The lack of texture on the figure’s head and the holes that are visible on it suggest that he might have once worn a helmet that is now lost. [4]

Mantiklos “Apollo” front, back, and side views, c. 700–675 B.C.E., bronze, 20.3 cm high (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The statue’s head is attached to an impossibly long neck. The figure has broad shoulders and a narrow waist, which is accentuated by a wide belt. While he looks rather flat from the front, the rounded, exaggerated musculature of his shoulders, buttocks, and thighs is more visible when we look at him from the back and side. The figure is elongated and extremely symmetrical, as is emphasized by the incised line that runs down his chest. [5] This symmetry is interrupted only by the figure’s raised left arm and slightly advanced left leg. The ideal that this figure embodies is not naturalistic. However, the suggestion of muscles in parts of his body—especially visible in his thighs, buttocks, and shoulders—adds some believable heft to his form. With his exaggerated muscles, elaborate hairstyle, and confident posture, the statue depicts a strong male figure that would have been understood as perfect by its original viewers.

Although the figure’s right arm is missing, his left arm remains bent in front of him. There is a small hole in his left fist, indicating that he once held something. This missing item would have helped us identify this statue, which probably represents either Mantiklos (the human dedicator of the object) or Apollo (the god to whom the object was dedicated). If the figure held a shield or spear, we would be able to recognize him as a warrior. If he held a bow, we would recognize him as Apollo, who was believed to be an excellent archer. Since the ancient Greeks thought that their gods looked like perfected humans, it is difficult to tell whether idealized representations like this one represent a god or a human when they are missing identifying attributes like a bow. [6] Because this statue’s identity remains ambiguous, it is today tentatively referred to as the Mantiklos “Apollo.”

The end of the Geometric

The Mantiklos “Apollo” was made around 700 B.C.E., as the Geometric period came to an end. It includes some elements of the Geometric style.

Left: Mantiklos “Apollo,” c. 700–675 B.C.E., bronze, 20.3 cm high (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston); right: Man and centaur, c. 750 B.C.E., bronze, 11.10 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

We can identify these elements by comparing the statue to another Geometric bronze votive that shows a man fighting a centaur. Both the Mantiklos “Apollo” and the man from the man and centaur group are overall rather flat (with the exception of their muscled behinds) and elongated. They are composed of simple shapes that make them easily understandable. But the shoulders of the Mantiklos “Apollo” are more believably rounded than those of the man fighting the centaur, and his muscles move somewhat more believably in his body. This is visible especially in the slightly swelling muscles of his lifted left arm. The anatomical details of his face and hand are also a bit more realistic. These differences reveal that in the 50 years that passed between the creation of the man and centaur group and the Mantiklos “Apollo,” ancient Greek artists and their customers began to embrace a slightly more naturalistic ideal.

The inscription

The ancient Greek written language was a relatively new invention when the Mantiklos “Apollo” was dedicated around 700 B.C.E. It emerged in the previous century, during the Geometric period, when Homer’s epic poems were first written down.

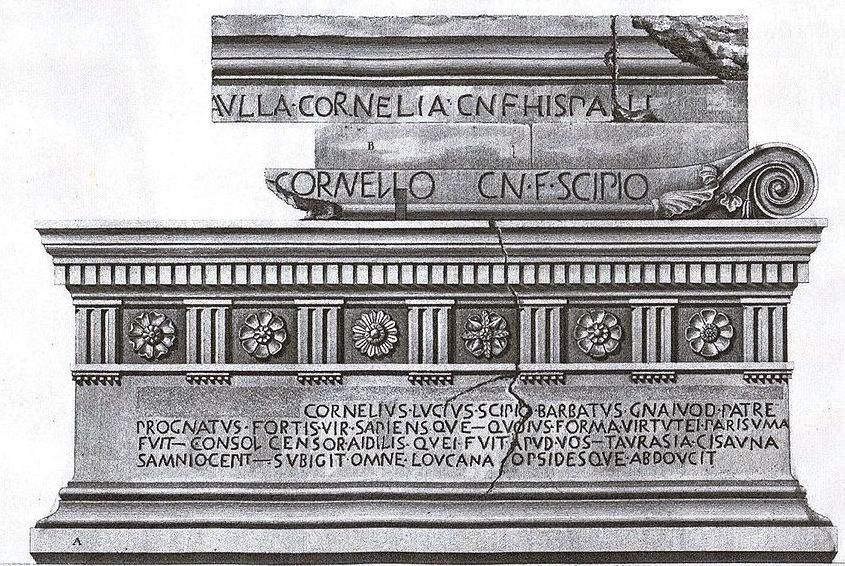

Inscription on thighs (detail), Mantiklos “Apollo,” c. 700–675 B.C.E., bronze, 20.3 cm high (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The inscription that runs along the thighs of our statue uses the same type of verse as Homer does in his poems. [7] The text is not written in straight, parallel lines, but instead in curving lines that echo the shape of the statue itself. [8] Since the inscription tells us so much about the artifact on which it appears, let’s consider it in full:

Mantiklos dedicated me as a tithe to the Far Shooter, the bearer of the Silver Bow. You, Phoibos [Shining One], give something pleasing in return.translation by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The inscription begins by naming Mantiklos, emphasizing his central role in the dedication of this votive. The phrasing “Mantiklos dedicated me” means that the inscription is written in the first person, as if the statue itself is speaking, explaining who dedicated it and for what purpose. The text then goes on to provide three different names for Apollo. “Far Shooter” and “bearer of the Silver Bow” both reference Apollo’s excellence in archery, while “Phoibos,” meaning shining one, is another nickname for the god. The inscription concludes by making a request of Apollo: “You, Phoibos, give something pleasing in return.” This sentence makes clear that Mantiklos is not giving this statue to the god simply to honor him. He is instead looking for a reciprocal relationship, in which he too will receive something. In ancient Greece, votive offerings were often given with this expectation. [9] They were believed to enact an exchange between a worshiper and the gods.

It is unlikely that many people could read in 700 B.C.E., but those few individuals who were literate likely read aloud. [10] When visiting the sanctuary in which the Mantiklos “Apollo” originally stood, worshipers may have listened as a fellow visitor read this verse aloud. The classicist Joseph Day has argued that Mantiklos’s votive offering would gain new life every time its inscription was read aloud, once again asking Apollo to give Mantiklos “something pleasing in return” for dedicating the elaborate little statue. [11] Even those who could not read or listen to the inscription might still admire its existence, as written text was a relatively new phenomenon in the Greek world.

Fulfilling a function

The form of the Mantiklos “Apollo” was carefully designed to help it fulfill its function of pleasing Apollo. The statue is made of an expensive, shiny metal that attracts the eye. It depicts an idealized figure whose beauty would appeal to the god. To represent this perfected male, the craftsperson who made the statue combined elements of the rigid Geometric style with more naturalistic details, thus creating a figure that embodies a new ideal that was just beginning to emerge when the statue was dedicated at the start of the Protoarchaic period. The inscription on the statue’s legs ensured that Apollo knew Mantiklos had given him the statue and expected to be rewarded in return. These elements were all devised to ensure that the Mantiklos “Apollo” would be a successful votive offering. They would also attract the attention of the many mortal worshipers who saw the figure on display in a sanctuary after it was dedicated. Many centuries later, the Mantiklos “Apollo” continues to impress us with its artistic accomplishment and remind us of Mantiklos’s devotion to his gods.